Generic products have been ‘growing the pie’ of the pharmaceutical market in Japan. Thanks to governmental efforts and initiatives designed to promote generic prescription drugs, the proportion of units of generic products in the Japanese market reached approximately 80% in 2021.

The expiry of the patent term of an innovator’s drug gives other pharmaceutical companies a chance to manufacture its generic product; i.e., a drug using the same active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). Generic drugs can be retailed at a lower price than an innovator’s drug due to their low production costs. However, a generic company is likely to violate a patent right of the innovator’s drug. This leads to an increasing number of patent disputes between innovators and generic companies.

One such case involves Warner-Lambert Company, which has filed lawsuits claiming patent infringement concerning an API, pregabalin (commonly known as Lyrica®), against several generic companies around the world. Warner-Lambert argues in its medical use patent of Lyrica® that it is effective in the treatment of symptoms of neuropathic pain and pain caused by fibromyalgia. Therefore, when a generic company wishes to obtain a drug approval, it needs to check the patent information on the existence of the innovator’s drug thoroughly.

In Japan, the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (MHLW) has introduced a ‘patent linkage’ system to ensure the stable market supply of generic products that may be disrupted by patent infringement claims filed after the sale of generic products has launched. The MHLW proceeds with the examination of a generic drug approval while referring to the patent information of the innovator’s drugs.

The patent linkage system is obscure in Japan because there are no provisions that stipulate the regulation, nor is the operation of the patent linkage system under Japanese legal practice clearly stated. This article will therefore provide an overview of the patent linkage system in Japan and discusses its challenges.

Overview of the patent linkage system in Japan

In principle, patent linkage is a system whereby a drug authority examines whether a generic product violates a patent right of an innovator’s drug before the authority determines the generic drug approval. The MHLW sets forth the following criteria for the examination in accordance with the “Announcement on handling medical patents pertaining to approval process and drug listing for generic products under the Pharmaceutical Affairs Law” issued on June 5 2009:

Where an API of an innovator’s drug includes a claimed invention, the MHLW will not grant a generic company approval of market entry of a generic drug;

Any generic product that has equivalent efficacy, effects, dosage, and amount of dosages related to the innovator’s drug will not be approved by the MHLW; and

Whether a patent right of an innovator’s drug exists is determined by the date on which approval is expected to be granted.

Only small-molecular medical products are subject to the MHLW’s notification above. Therefore, biopharmaceuticals are not subject to the notification.

The procedures of the notification are as follows:

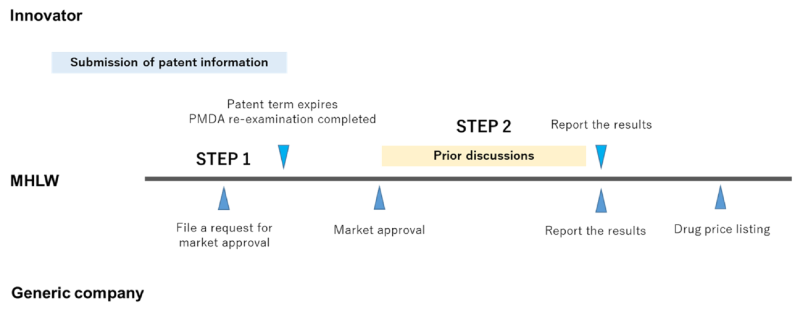

The MHLW requests an innovator to submit “a report on patent information of the innovator’s drug” regarding protection of a substance patent or a use patent of the product. The submission is not mandatory, and the content of the information is not disclosed in public.

The report contains a substance patent or a use patent of the marketed product that pertains to an API of the product, except for in vitro diagnostic drugs. The submission is accepted until the time when the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency has completed its re-examination investigation of an innovator’s drug (even if the re-examination is not completed, the submission is accepted until the patent term expires).

The MHLW checks the patent information of the innovator’s drug twice. The first instance is at the examination stage of a generic product and the second is at the time of the pre-stage of the drug price listing.

In the first stage, the MHLW subjectively examines whether a generic product can be authorised based on patent information. In the second stage, the MHLW offers an opportunity for the innovator and the generic company to discuss whether the generic product in application may infringe upon the innovator’s drug (prior discussions). When the discussion is over, both parties report on the results to the MHLW.

There are two important considerations.

In the first stage, the MHLW merely refers to the patent information so as to check the patent status. The MHLW does not examine its patentability. The MHLW would follow the JPO examination results. If an invalidation trial is pending at the JPO, the MHLW apparently will not grant market approval for the generic product.

Furthermore, the second stage is carried out mainly by the parties involved and therefore the MHLW will not take a position on intervening in a further patent litigation between the parties. Discussion between the parties may result in the generic company withdrawing its application or the innovator filing a patent litigation against the generic company. As long as the application is not withdrawn by the generic company, the MHLW will proceed with the examination on market approval.

Legal comparison between significant jurisdictions

The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) was signed by 11 countries, including Japan, and came into effect in December 2018. The CPTPP provisions stipulate the strength of intellectual property rights protection, one of which suggests the implementation of the patent linkage system, which serves as a framework for considering a patent in force when a generic product is granted market approval (Article 18-53).

The operation and utilisation of patent linkage systems vary from country to country. The patent linkage system has been introduced to disclose patent information on innovators’ drugs in the US but not in the EU. Countries such as Canada, Australia, and South Korea follow a similar system to that of the US.

US practice

With regard to market approval of generic drugs, the US introduced the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act in 1984 (after amendments, dubbed the ‘Hatch–Waxman Amendments’), which consists of three main provisions:

Disclosing patent information on an innovator’s drug;

Notifying to a patent holder that a generic company is seeking market approval of its generic product; and

Offering the opportunity for an innovator and a generic company to discuss the resolution of a dispute over an allegedly infringing product.

The Food and Drug Agency (FDA) examines the bioequivalence between an innovator’s drug and a generic drug and publishes the results in the Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (commonly known as ‘the Orange Book’).

Once an innovator obtains a new drug approval from the FDA, the innovator must identify and submit all the relevant information involved in the patent that other manufacturers and distributors are likely to infringe upon manufacturing the pharmaceutical products in question. The patent information should cover the scope of the claimed invention related to the method and the product itself. These steps are also required when an innovator renews its information (21 USC 355(b)(1)).

The Orange Book covers a substance patent of an API, a use patent, and a formulation patent pertaining to chemicals and pharmaceuticals.

On the other hand, the generic company files an abbreviated new drug application (ANDA) to the FDA. The first-to-file abbreviated new drug applicant is entitled to be granted market exclusivity on the generic drug market. Every time a generic company files an ANDA, a patent holder/innovator needs to consider possible patent infringement litigation regarding its patent.

Chinese practice

China has introduced a system similar to that used in the US. In July 2021, a platform listing patent information on market-approved drug products was opened.

The platform discloses not only patent information on an innovator’s drugs but also the content of the drug approval request filed by the generic company, which contains the patent information related to its generic product. Information related to pharmaceuticals, biopharmaceuticals, and herbal medicines is available on the platform. Similar to the US system, the first-to-file applicant is entitled to be granted one year’s market exclusivity in the generic drug market.

Future challenges and key considerations

As described above, the Japanese patent linkage system is unique. It is widely evaluated that the system helps to avoid unnecessary litigation. However, compared with the US and Chinese practices, which clearly state operations in the regulations and disclose patent information on innovators’ drugs, it can be said that the Japanese system lacks transparency and clarity of operation. In addition, in terms of expertise, the MHLW subjectively examines market approval based on the patent information, and it can be easily argued that the examination criteria are obscure.

At the initial negotiation stage of the CPTPP agreement (previously the TPP agreement), Japan considered whether the US-type patent linkage system could be applied. However, the high frequency of patent litigation was of great concern in the pharmaceutical industry and therefore innovators and generic companies were opposed to establishing a concrete system.

Moreover, the present system is only applied to small-molecule products. There will be further discussions as to whether biosimilar products should be subject to the system.

It is necessary to establish a system that can satisfy the needs of pharmaceutical companies in this ever-changing market. The law will need to be enacted with clarity to protect the intellectual property rights of pharmaceutical companies, which are expected to become more diversified across various businesses and fields.