1. The metaverse in China

(1) General status and development

The metaverse refers to the next generation of the internet, where users can ‘step inside’ a 3D version of the internet and experience it via virtual reality, augmented reality, or mixed reality, focusing on social communication. The metaverse-related industry has experienced robust growth in leading economies and has been developing and gaining a foothold in many sectors. Metaverse-related technology is developing in many aspects.

In China, the legality of metaverse-related business has experienced a tortuous path, which has reflected the hesitation of regulators in deciding whether to embrace or resist this new and unknown business. Nonetheless, this attitude has softened in recent months since the Shanghai municipal government published its 14th Five-Year Plan for the Digital Economy in July, which includes the provision to “support key enterprises to explore the construction of NFT [non-fungible token] transactional platforms”.

It is presumed that the Chinese government may have gradually understood that the development of the metaverse and NFTs will have an unknown positive influence on, and potential for, the digital economy as a whole.

(2) The nature of NFTs

An NFT is a unique digital identifier that:

Cannot be copied, substituted, or subdivided;

Is recorded in a blockchain; and

Is used to certify authenticity and ownership.

Although there have been no statutes in China to establish the legal nature of NFTs, in Qice v HZ Yuanyuzhou, the first NFT-related judgment in China, the Hangzhou Internet Court ruled that an NFT-related transaction is essentially a transaction regarding digital content and that the subject matter that the purchaser acquired is its property right.

It could therefore be inferred that the property rights of NFTs, just like land or houses, are protectable under property law, which shall be regarded separately from associated intellectual property rights.

In the meantime, NFTs, the most fundamental subject matter in the metaverse, are allowed to be the subject of only one transaction after their issuance by major platforms, according to their published rules. Among the ten largest NFT platforms in China, six do not support resale in the secondary market, while three support re-transfer as a gift without consideration.

2. The metaverse and trademark registration

The ownership of an NFT does not mean that the owner has its intellectual property (IP) rights. Any IP rights shall be acquired according to the law.

Trademark rights are mostly acquired via an application procedure. Tahota Law Firm’s research of leading IT platforms and international brands, particularly in the sports industry, reveals that they have been actively registering marks in relevant categories of goods or services.

(1) Domestic IT giants

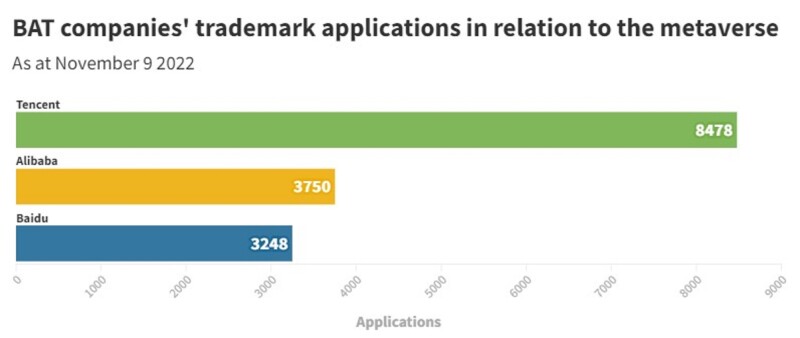

Unsurprisingly, the largest IT companies, including BAT (Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent), have been actively creating layouts of trademark application maps in relation to the metaverse. Baidu owns 3,248 applications, Alibaba owns 3,750 applications, and Tencent owns 8,478 applications in related classes of goods and services covering the main areas of the metaverse.

(2) International brands

International brands such as Nike are also actively expanding their maps in laying out applications for the metaverse industry in China. According to the database of the CNIPA, Nike has applied for 19 marks in relation to the metaverse, covering goods and services in Class 9 and Class 35.

(3) Earlier filing

As discussed above, the acquisition of an NFT does not imply that the related IP has been acquired, assigned, or licensed to the NFT buyer. Therefore, registration remains a fundamental and an important step in protecting IP rights.

An undeniable fact of Chinese trademark practice is that the filing of an application is much cheaper and efficient than the prosecution proceedings to invalidate or purchase those pre-emptive registrations due to the first-to-file principle, taking into account that pre-emptive registration is already a serious issue in the jurisdiction. It would therefore be worthwhile for brand owners to consider taking proactive action in filing their marks as early as possible.

(4) Classes of designated goods

The selection of designated goods or services in this regard would be important as well. The CNIPA is working on a revision of the Name List of Classification of Goods to fit the need for registration covering new goods and services in this regard.

With regard to designated goods, a few categories are regarded as important to metaverse players, which includes classes 9, 35, 41, and 42. The following subgroups and items have been regarded by brand owners as important to protect metaverse-related goods and services.

0901 | Video game programs |

0901 | Downloadable video game programs |

0901 | Computer software applications, downloadable |

0901 | Computer programs, downloadable |

0901 | Computer software, recorded |

0901 | Interactive multimedia computer game programs |

0901 | Computer gaming software downloadable from global computer networks and wireless devices |

0901 | Virtual reality game software |

0901 | Computer game software, downloadable |

0901 | Computer game software, recorded |

0901 | Digital gaming software for download |

0901 | Mobile phone software applications, downloadable |

3501 | Presentation of goods on communication media, for retail purposes |

3503 | Provision of an online marketplace for buyers and sellers of goods and services |

3503 | Targeted marketing |

3501 | Advertising |

3503 | Sales promotion for others |

3501 | Online promotion of computer networks and websites |

3502 | Providing an online business information catalogue on the internet |

4105 | Gaming services provided online from a computer network |

4105 | Virtual reality gaming services provided online from a computer network |

4105 | Entertainment services |

4105 | Providing online videos, not downloadable |

4105 | Video game console rental |

4105 | Providing online computer games |

4105 | Video game services provided via the internet |

4220 | Computer programming |

4220 | Computer video game programming |

4220 | Computer game programming |

4220 | Multimedia application programming |

4220 | Development of video and computer games |

4220 | Video game development services |

4220 | Design and development of virtual reality software |

4220 | Software design and development |

4220 | Design and development of multimedia products |

4220 | Computer graphic design |

4220 | Electronic data storage |

4220 | Data conversion of electronic information |

4220 | Software as a service |

4218 | Dress designing |

4227 | Animating for others |

3. The metaverse and trademark protection

(1) Classification, the confusion test, and use in a trademark sense

As discussed, most of the present NFTs in China are preserved by owners for collection as souvenirs, given the prohibition or restriction against secondary transaction and financialisation. Therefore, NFTs in the metaverse and products in the real world are generally regarded as separated and have limited connection with each other.

The question is whether the use of a mark in NFTs shall be considered as being used for goods or services similar to the corresponding real-world goods or services. For example, a bag bearing a designer mark and an NFT of a bag bearing the same mark, or a fast-food shop in the real world and its corresponding NFT shop.

No court decisions have been made on metaverse-related trademark infringement cases in China. However, in the US, precedents have already been established.

In AM General v Activision Blizzard, the court ruled that Activision Blizzard’s interest in presenting military verisimilitude easily met the low bar for artistic relevance. Furthermore, by using ‘the Polaroid Factors’, the court determined that Activision Blizzard’s use of Humvees was not explicitly misleading. Although some surveys did show some potential confusion among users, the fact that AM General was a manufacturer of vehicles and Activision Blizzard was a producer of video games heavily weighed against such assumptions.

In its decision to grant a summary judgment to Activision Blizzard against all of AM General’s claims, the court held that “enhancing the games’ realism” was enough to determine the use of Humvees as part of the games’ artistic expression.

In China, according to Article 11 of the Interpretation of the Supreme People's Court on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Law in the Hearing of Civil Cases Involving Trademark Disputes (Amended in 2020), "similar goods" as mentioned in Item (2) of Article 57 of the Trademark Law of the People’s Republic of China shall mean goods that have identical functions, uses, production entities, sales channels, target consumers, etc., or goods that the relevant public generally considers to have a certain connection and that are likely to cause confusion.

Given the analysis provided in the section regarding trademark registrations, the author generally thinks that it could be difficult to find identity between physical designated goods and corresponding NFTs. However, whether they could be found as similar will largely depend on how the business model in the metaverse develops, along with other Web3 technology developments.

Specifically, the question is whether the NFT will continue to be regarded as a souvenir or token in the ‘magic world’ of the metaverse or if it will be a representation of real-world products and substitutive of them in terms of functions, uses, production entities, sales channels, target consumers, etc., or at least share certain connections.

Besides, given the increasing number of brand owners that conduct promotional or advertising activities for the distribution of real-world products in the metaverse, such use will likely link the NFT and its real-world counterparts. Thus, such use of mark in advertising activities in a promotional NFT could be more likely to be found as identical or similar to the real world products or services due to their similarities, in uses, sales channels, and target consumers.

For example, if a company registered a mark in Class 9 with regard to gaming software while using the mark as the NFT of shoes and another company used the same mark concerning real shoe products without authorisation from the registrant, then whether such use shall be found as infringing will depend on whether the use may cause confusion to consumers. Such confused fact-findings will result from the business custom concerning the products in the metaverse and the real world, and how consumers would perceive their relationship at that point.

If the development of metaverse technology will result in the commercial implication that the pair of NFT shoes functions as the advertisement of the real shoes, then the risk of finding infringement will be substantial. By contrast, if the technological development of the metaverse did not sufficiently support that the NFTs have such function – rather, would it be used as an artistic visual token with purely entertainment or aesthetical merit – then the finding of infringement would be difficult.

By the same token, Article 48 of the Trademark Law also provides that use in a trademark sense shall mean the use of a trademark on commodities, commodity packaging or containers, or commercial transaction documents, or the use of a trademark in advertisement and promotion, exhibition, and other commercial activities, for identifying the source of commodities.

Therefore, if the use of a mark in the NFT products contributes to the purpose of identifying the source of real goods rather than the display of the token for enjoyment, then use in a trademark sense could be found as well, which is another condition in a finding of infringement.

(2) Well-known mark protection

According to Article 9 of the Interpretation of the Supreme People's Court on Several Issues Relating to Laws Applicable to Trial of Civil Dispute Cases Involving Protection of Well-known Trademarks, the confusion test in the sense of well-known mark protection shall include:

Direct confusion; namely, confusion on the origin of goods; and

Indirect confusion; namely, confusion on possible association.

The latter also includes dilution and tarnishment.

Under such laws, it could be possible to find the unauthorised use of the metaverse as infringement against the well-known mark. In the US, there have been precedents in this regard. In Hermès v Rothschild, the court ruled that Rothschild “designed and marketed”, and then sold, using NFTs. “Like the physical Birkin handbag itself, MetaBirkins are extremely valuable commodities,” the court asserted, noting that “the NFTs have sold for over a million dollars collectively.”

The ruling added: “Consumers and media outlets have expressed actual confusion as to whether Hermès is affiliated with Rothschild’s line of NFTs, with many believing it to be the product of a partnership between the two.”

In China, although there has been no court decision in this regard, it would not be surprising were a Chinese court to rule that the use of a mark in NFTs may cause confusion to consumers or they are found as diluting the distinctiveness of well-known marks, assuming that the development of technology will necessarily promote the interaction between real-world products and their NFTs as a whole.

(3) Evidence collection and enforcement of an injunctive order

Given that NFTs are built on the basis of blockchain, which is technically unchangeable, this feature will be helpful with regard to evidence preservation in comparison with other IP infringements in the real world.

Another issue that has caused debate is the enforcement of a judgment by judicial or administrative bodies. Under the Trademark Law, trademark owners are authorised to seek for injunction in an infringement case. The administrative enforcement agencies are also authorised to issue an administrative order to cease the infringement. If an injunction is granted to a trademark owner by a judicial or an administrative organ, then the infringer is obliged to cease the infringements.

The most extreme measure against an infringing NFT would be to type the token into a black hole address, thus terminating the possibility of any further transactions involving the token.

4. The metaverse and territoriality

Another issue would be territoriality. Similar to e-commerce under the Web2 environment, Web3 could also result in cross-border business in spite of the territoriality of registration of a trademark.

Then the question would be whether to find the use of a trademark in the NFT of another jurisdiction as infringing the trademark registration in the home country, given that the trademark could be perceivable to consumers in the home country as well.

5. The prospect of trademark protection of NFTs

As discussed above, the trademark issue in the metaverse is in the process of development and far from being settled, as the technology is developing and the laws are evolving. The common belief of the international IP community is that issues in the new sphere should be regulated under the present legal system. However, whether that approach is correct remains to be seen.

We should keep watching the progress of this new technology and figure out how to adapt development in the IP mechanism.