Bayer Intellectual Property GmbH (Bayer) owns the compound patent ZL00818966.8 of the blockbuster anticoagulant drug rivaroxaban, which is marketed as Xarelto. Rivaroxaban is a direct inhibitor of factor Xa (FXa), a coagulation factor at a critical juncture in the blood coagulation pathways leading to thrombin generation and clot formation.

A cohort of pharmaceutical companies, including Nanjing Chia Tai Tianqing Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd (the petitioner), launched within a year multiple invalidity challenges targeting the above patent.

In the petition for invalidation, the petitioner asserted that the rivaroxaban compound is devoid of inventiveness, citing more than a dozen pieces of evidence and proposing dozens of combinations of evidence.

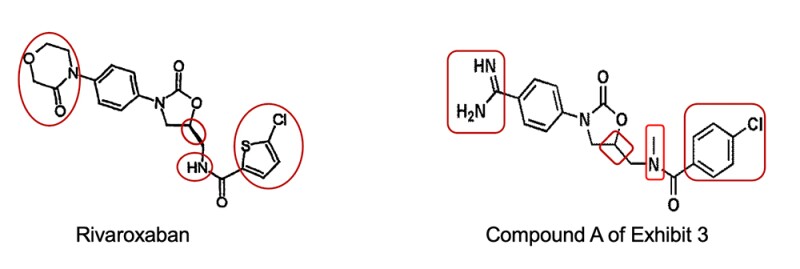

Taking Compound A of Exhibit 3 as the closest prior art, the petitioner alleged that both rivaroxaban and Compound A are inhibitors of FXa. The petitioner also argued that the two compounds share two identical rings (phenyloxazolidinone) in terms of structure and differ in the morpholinone fragment on the left of rivaroxaban and the 5-chloro-thiophene group on the right, but those fragments can be found in the relevant compounds cited by other evidence, thus concluded that there is motivation for obtaining rivaroxaban.

The invalidity decision rendered by China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) found the arguments inadmissible. The invalidity decision opined that pursuant to the ‘three-step method’ commonly used in the assessment of inventive step, the technical problem actually solved by the patent is to provide a compound having good inhibitory activity against FXa. Nevertheless, in order to solve this problem, those skilled in the art are not motivated to modify Compound A with those distinct structures and obtain rivaroxaban. The invalidity decision therefore concluded that the claimed compound, rivaroxaban, is inventive.

Invalidity decision

The invalidity decision elucidates that Exhibit 3 is a patent application entitled ‘Benzamidine derivatives’, with all the example compounds containing benzamidine or amidine radical. Rivaroxaban and Compound A share the same structure of the two rings (phenyloxazolidinone) in the middle, yet many example compounds cited in Exhibit 3 are devoid of such structure, thus conclusion cannot be drawn as to compounds with the same structure have inhibitory activity against FXa.

To improve the inhibitory activity of FXa, Exhibit 3 gives the technical teaching to keep the structure of benzamidine or amidine unchanged and modify Compound A at other positions, rather than to remove the structure of benzamidine or amidine and retain the moiety of phenylene oxazolidinone amino structure.

In practice, the first step a skilled person, who is tasked to structurally modify a compound, would take is to identify the site for modification, which is to be followed with selection of a radical in the field in view of the properties of radicals or teachings about structures and properties. Apparently, structural modification is not a process of cobbling together individual radicals from compounds with different structures in the prior art.

As regards the morpholinone structure, notwithstanding the presence of morpholino radical in the compound cited in Exhibit 5, there is no technical teaching that piecing the morpholine radical to Compound A to replace the amidine radical will achieve better inhibitory activity against FXa. Moreover, according to the prior art, the amidine radical in the benzamidine compounds binds with S1 pocket of FXa. However, the radicals that the petitioner found to replace the amidine radical of Compound A from other evidence are not the radicals bound with S1 pocket, therefore there is no substitution motivation.

As regards the moiety of 5-chlorothiophen-2-yl, those skilled in the art, by leveraging the overall teaching in Exhibits 3 and 5, are incapable of figuring out how to select a site for modification. The structure of the compounds cited in Exhibit 5 is fundamentally different. There is no technical teaching in the prior art as to identifying and substituting the radical in a compound with completely different structure.

Based on the above reasoning, CNIPA rendered on September 3 2020 an invalidity decision, finding the patented pharmaceutical compound rivaroxaban non-obvious and inventive and maintaining the validity of the patent on the basis of amended claims. The case was selected as one of CNIPA’s Top Ten Patent Reexamination and Invalidation Cases in 2020.

The three-step method and SAR

Pharmaceutical compound patent is the jewel in the crown of drug patents. Drugs with good market prospects often fall victim to patent invalidation actions initiated by rivals or generic drug companies, with the validity of compound patent being challenged on a frequent basis. The focus of contest ultimately lies in the inventiveness of compound.

Chapter 10 of the newly revised ‘Guidelines for Patent Examination’, which enters into force as of January 15 2021, affirms that pharmaceutical compound patent follows the ‘three-step method’ in the determination of non-obviousness, with reference to auxiliary factors, inter alia, unexpected technical effects.

Where the determination of non-obviousness suffices to lead to a conclusive finding on the inventiveness of the patent, auxiliary factors are unlikely to take centre stage in the determination of inventiveness. In this case, although the patentee raised unexpected technical effects in its validity defence and adduced corroborative evidence, the invalidity decision ascertained the inventiveness of the patent based on the non-obviousness finding, without addressing this particular issue.

In practice, controversy may easily arise in each step of applying the ‘three-step method’ in ascertaining the obviousness of a compound, namely:

How to determine the closest compound in the first step;

How to determine the technical contribution of the invention so as to reasonably determine the actual technical problem being solved; and

How to ascertain whether there is technical motivation for structural modification in the prior art.

The controversy in the case dwells on the issue of technical motivation, that is, how those skilled in the art would modify the structure of Compound A and whether they would be motivated to adopt the structure of invention to solve the corresponding technical problem.

A further analysis of the invalidity decision affirms that the teaching of specific drug structure-activity relationship (SAR) is pivotal in ascertaining whether there is a motivation in the prior art as to transforming Compound A into rivaroxaban structure. This aligns perfectly with the orientation of the ‘three-step method’ in solving the technical problems. Also in R&D practice, the structure-activity relationship navigates the drug discovery process.

The pivotal role of SAR

A full understanding of the structure-activity relationship is conducive to reasonably identifying the core structure for modification. The structural modification of a compound is usually the result of radical substitution on the core structure.

In the context of the three-step method in flashback, the closest compound is the one with the most similar structure selected from the prior art with the prior knowledge of the structure of the patented compound, which is a process with hindsight. The identical structural part shared by the cited compound and the patented compound is naturally used as the basis for the next step group substitution. In theory, however, structural modification could occur at any position of the closest compound, even in the common structure between the two compounds. Thus, the question that needs to be answered in the first place is, why those skilled in the art are to retain this ‘same structure’ and make it the core structure to modify other moieties, rather than to directly modify the ‘same structure’, which structure-activity relationship could help to answer.

As the invalidity decision underscores: “To modify a compound, the first step is to identify the site for modification.” In this case, the petitioner argued for the substitution of the benzamidine moiety on the ‘phenyloxazolidinone’ core structure of Compound A, which contravene the structures-activity relationship teaching revealed in Exhibit 3, that is, benzamidine other than phenyloxazolidinone is a necessary structure for the compounds throughout Exhibit 3.

The structure-activity relationship guiding the structural modification should be explicit rather than broad. This particular structure-activity relationship embodies specific mode of interaction between the compound and the specific target.

The process of modern drug discovery usually starts from the discovery and identification of a target. Based on the interaction of compound structure and target, lead compounds are singled out and optimised, through which process candidate compounds are generated.

The structure-activity relationship in this case is embodied in the interaction between the compound and FXa. In this sense, anticoagulant compounds with different targets of action do not provide structural guidance for FXa inhibitors. Furthermore, structure that binds with one site of FXa does not provide guidance for structure that binds with another site. As the invalidity decision put it, “as for the radicals in Exhibits 6, 8 and 9, based on the studies on S1 and S4 pockets in Exhibits 4, those cited in Exhibits 6, 8 and 9 do not bind with S1 pocket, not to mention technical motivation for using the aforesaid radicals to make the modification.”

SAR roots in prior art

The exploration of the structure-activity relationship should take root in the prior art, especially the holistic teaching of the closest prior art documents. The modification of the closest compound by those skilled in the art is first influenced by the closest prior art documents. In this case, the closest prior art document, i.e. Exhibit 3, is an important basis for the structure-activity relationship.

Exhibit 3 neither directly addressed structure-activity relationship nor gave any activity data of the compounds. However, the title of the invention, the general formula of the definition, the structures of the specific compounds prepared and other overall contents still convey the information in terms of the direction of structural modification to those skilled in the art, that is, the benzamidine structure is a necessary structure for the realisation of FXa inhibitory activity. This information is corroborated by the teachings of the petitioner's other evidence, thus the understanding of structure-activity relationship of the compounds cited in Exhibit 3 by those skilled in the art can be established.

The structural modification of drug compounds cannot digress from the structure-activity relationship. In the process of structural modification of a compound, it is always important to ask why those skilled in the art are making such modification and how the overall activity of the final compound is expected to change after such modification. Only in this way can ‘hindsight’ on the determination of the technical motivation be avoided to the most extent and jurisprudence does not contradict common sense in the R&D practice of drugs.

Honghui Hu

Partner

Wanhuida Intellectual Property

T:+86 10 6892 1000

Honghui Hu is a partner and a senior patent counsel of Wanhuida Intellectual Property. She is qualified both as a patent attorney and as a lawyer in China.

Honghui has extensive experience in prosecuting and litigating patent and technology-related matters, with her technical expertise primarily focusing on chemistry, biotech, pharmaceutical and food technology. She excels in advising clients on intricate matters like patent validity analysis, freedom-to-operate and infringement risk assessment. She frequently advises multinational corporations in the pharmaceutical, biotech and chemistry industries.

Honghui is one of the lead counsels that helped defend the validity of Bayer’s compound patent of blockbuster anticoagulant drug rivaroxaban, a case selected as one of CNIPA’s Top Ten Patent Reexamination and Invalidation Cases in 2020.