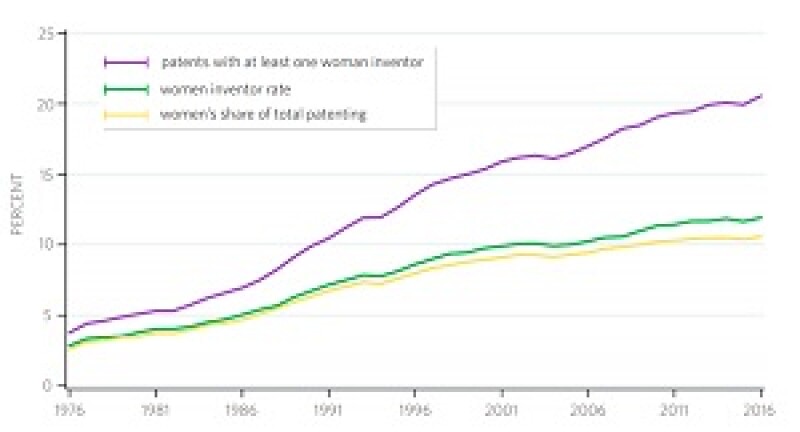

A February USPTO report profiling American women inventors revealed that women remain dramatically underrepresented in the patent world. Despite accounting for over half the US population, women made up just 12% of patent authors in 2016 – the latest year for which data is available.

Another statistic is more encouraging: the number of US patents with at least one woman inventor grew from 7% in the 1980s to 21% by 2016.

Despite the growth trends depicted, the rates of growth are slowing, which is “quite concerning”, according to Scott Barker, director of global patent development at Micron. “At 12%, the number of women inventors is shockingly low”, he says, “and highlights that as organisations, we’re not leveraging those assets”.

Inventorship outside the US is not much better; according to a 2017 WIPO report, 30.5% of international patent applications include at least one women inventor. It says that global gender parity in inventorship remains “a distant prospect”. The Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR) predicts that true parity in inventorship won’t be achieved until 2092 at the earliest, based on current trends.

Value of diversity in IP

These numbers are distressing not only because women have been excluded from a critical industry, but because they demonstrate that society as a whole has lost out as a result. Barker calls the untold numbers of women who could have been great innovators “lost Edisons”, and says “all companies should prioritise leveraging these untapped resources”.

Sandra Nowak, assistant chief IP counsel at 3M, agrees that gender parity in IP is important because “strong IP creation is a team sport that requires diversity and a global mindset”. On a personal note, she adds: “Working with people who think differently than I do and who I can learn from makes the job much more fun.”

On a practical level, Margaret Walker, associate general IP counsel at Xerox, notes that “to the extent that necessity is the mother of invention, women have a tremendous role to play” because they have unique and valuable perspectives, particularly around issues that only affect women.

Because IP is involved in so many levels of a business, says Angela Johnson, litigation counsel at Uber, “it’s important to have those diverse perspectives at each stage”.

The Women in IP committee within the US-based Intellectual Property Owners Association (IPO) reports that gender-diverse companies are 15% more likely to financially outperform non-diverse companies. “I’m not saying we’re smarter”, quips Mercedes Meyer, partner at Drinker Biddle in Washington, DC, “but we obviously bring something different to the table”.

Meyer asserts that outdated ideals of what IP lawyers look like are societal algorithms that inhibit potential and ultimately affect the bottom line. “If innovation is brought forward, you can add to your bottom line. If you delay, there’s an opportunity cost. Isn’t that enough economic incentive?”

Barriers to progress

The economic argument for diversity has been paid lip service for decades, but inertia has prevented measures for change from taking effect. IP is a niche at the intersection of two male-dominated spheres: law and STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths). Gillian Thackray, chief IP counsel at Thermofisher, explains: “In IP, the legal and science pipelines have been restricted for women”.

Due to a multitude of gender-related factors, female engagement with STEM is low, starting in early education. This plays out over time; the IWPR reports that women only account for 29% of the STEM workforce in the US. Even in areas where there are more women in the workforce, inventorship is still lagging. Increasing female participation in science, engineering and entrepreneurship is not translating into corresponding increases in female inventorship.

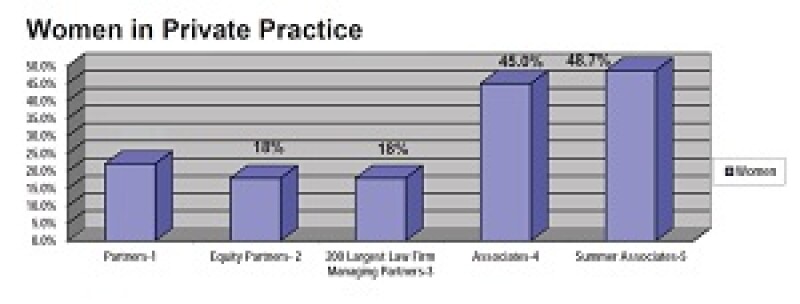

On the legal side of the equation, equality seems more achievable. Female law school graduates now outnumber their male counterparts, yet women’s representation in law dwindles with seniority.

However, “it’s not just a pipeline problem”, according to Thackray. When the number of female law school graduates matched the number of male graduates for the first time in the 1990s, she tells Managing IP, “people thought equality would only be a matter of time.” Now, 20 years later, “it did not lead to a sea change in the profession as expected”.

While education and practice in STEM and law may have systemic issues that have created a less-than-welcoming environment for women in IP, Micron’s Barker contends that individual organisations have the power and responsibility to create their own cultures.

The stagnancy until now has primarily a cultural cause. Barker says that the “patent industry has a tendency to fall into the tried and true, and doesn’t look proactively for change as much as our business counterparts do”.

For example, the traditional US method of patenting relies on inventors to self-identify and submit disclosures, but Barker recognises this could present barriers to women. “Don’t assume that just because you have an invention disclosure receptacle that everyone is going to use it”, he says.

Thermofisher’s Thackray agrees that IP’s gender issues relate to an unwillingness to change. “The profession is risk-averse”, she explains, “which creates a current you’re constantly swimming against. When you’re struggling upstream and get no encouragement, you think, why am I here?” Many women leave the field, never making it to the highest levels of IP.

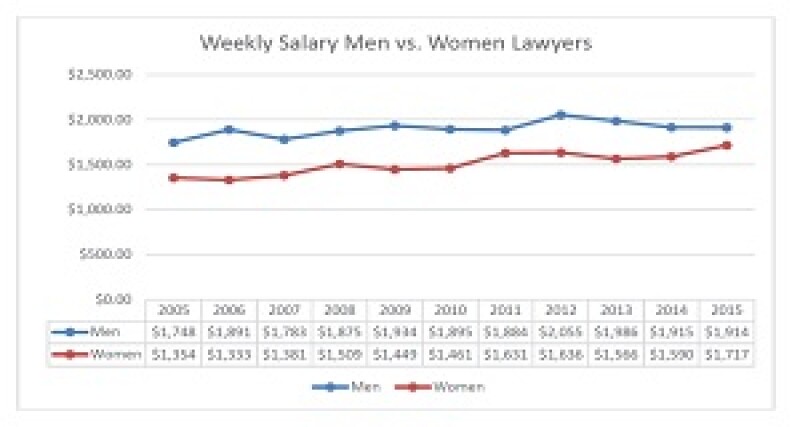

According to a survey by the IPO’s Women in IP committee, the top reasons women leave law firms are: lack of mentorship; unsatisfying upward mobility; limited meaningful work; vague feedback; a lack of work-life balance; and the wage gap.

Law firms v corporations

The wage gap is another factor contributing towards low levels of female inventorship. Patents are expensive to obtain, and the costs can be disproportionately prohibitive to women because they earn less, on average.

“Corporations have been quite a bit more out in front than law firms” in terms of gender diversity, Thackray, of Thermofisher, says. Women often find in-house more hospitable, because the job is focused on more than pure hours logged. According to Thackray, law firms realised that they needed to recruit women decades ago, but would not necessarily take steps to include them. However, “firms have started catching up in the last three to four years,” she says.

This progress coincides with pressure from corporations, which are demanding their outside counsel meet certain diversity requirements. Organisations like the Leadership Council on Legal Diversity (LCLD) and DiversityLab track companies’ diversity incentives, among other projects.

For example, HP enacted a policy that would penalise its outside counsel in 2017 by withholding 10% of fees if they fail to meet diversity requirements. Also in 2017, Facebook created a requirement that women and minorities must account for at least 33% of their outside legal teams, according to the New York Times. The article quotes Jean Lee, chief executive of the Minority Corporate Counsel Association: “Companies are now using a carrot and stick approach because the carrot approach alone didn’t work”.

Mentorship – the silver bullet?

Woven throughout the stories of top women in IP’s struggles and ultimate successes is a coherent thread: mentorship. Ideally, direct role models are available to demonstrate exactly what success as a woman in IP can look like. “Being able to picture yourself as part of the mix gives us all the motivation to stick with it”, says Thackray.

Xerox’s Walker adds: “Young girls and women want and need to see women in powerful roles. It gives them permission to see themselves occupying the same positions”. Diversity efforts are often focused on hiring practices for lower-level positions, but Uber counsel Johnson notes that it’s important to have diverse people at all levels of the hierarchy.

In fact, the USPTO’s report on women inventors found that they are increasingly concentrated in specific technologies, suggesting that women are specialising in areas where female predecessors have traditionally patented, rather than entering into male-dominated fields.

Where direct role models are unavailable to women in IP, male mentors and advocates can also provide invaluable support. “Given the lack of women in IP, male partnership has been critical”, says Thackray. At Xerox, accessing networks of successful men both within and outside the organisation is “crucial”, according to Walker, because “advocating for women is needed in order to be truly successful”.

For example, women in many fields are facing professional uncertainty due to the ongoing #METOO movement. Some men are now more hesitant to hire, promote, or work with women for fear of sexual misconduct allegations. Meyer says the #METOO movement could hurt women in IP because “if men don’t mentor women, it’s a problem”.

However, Thackray calls the #METOO setback a red herring, because “these problems are easy to solve if you have an ounce of creativity. Afraid to take a woman to lunch? Take two women to lunch!” As this issue is brought up when women are not around, Thackray hopes there are enough intelligent men out there who will call other men out on the false premise. “This is why men’s participation in diversity initiatives is so important”, she says. “The group that’s out of power can’t do it alone”.

In a litigation context, studies have shown jurors are more sceptical of women’s competence in the courtroom, according to Dale Cendali, partner at Kirkland & Ellis in NYC. But if women can establish their competence, she says, jurors are more likely to believe women’s sincerity. “They’re more apt to believe men are competent, but also willing to be a hired gun. If that’s true and you’re able to prove yourself competent, being a woman could be an advantage, assuming the opposing counsel is male”.

Uber’s Johnson adds that as a litigator, she’s “always thinking about how a jury will perceive things”, adding: “I look at it differently than someone who’s not a woman or not a person of colour.”

The elusive talent magnet

Attracting and retaining talented women starts with what makes any job satisfying: “interesting work, and good pay and benefits”, says 3M’s Nowak. Beyond those basics, Xerox’s Walker emphasises the importance of illuminating clear pathways to promotion. “The status quo does not work”, she says. “Affirmative efforts are required to overcome years and years of inherent bias and disadvantage”.

Such efforts could include introducing additional flexibility around working hours and particularly parental leave, because parenthood has a disproportionate impact on women. Thermofisher’s Thackray explains: “The legal profession is so demanding and so unforgiving to people who take time off to parent, it’s a talent drain”.

Companies and law firms are both struggling with this. “IP needs to do a better job accomodating the needs of parents so people don’t have to choose between being a good parent and being a lawyer”, Thackray says. From a diversity perspective, she argues being a parent makes people better lawyers because the experience grants them better empathy and a new perspective on life.

There are undoubtedly perfectly qualified diverse candidates in IP, but when it comes to hiring practices, Uber’s Johnson says a thorough and unbiased search may require a little more time. “If you’re always going to the same sources and they're not bringing diverse candidates, you might not find someone right away”, she says.

The best way to find diverse qualified candidates, according to Johnson, is to tap into existing networks and incentivise diverse referrals. From college campuses to law schools and Bar associations, there are affinity groups across the diversity spectrum. “Once you know they exist, simply go to their events and network”, she explains. Using diversity-focused recruiting firms can simplify this process. Also, resume-sorting artificially intelligent programmes can help limit hiring managers’ biases.

Building a women-friendly culture

The most important characteristic that attracts talented women to a workplace is an inclusive environment. “If culture is tied to race or gender, it’s problematic,” says Johnson. But if culture is based on values like collaboration and innovation, there is a greater opportunity for women to thrive. Johnson says she was first attracted to Uber for its culture of innovation. “As a startup it’s not stuck in hierarchy or red tape, but it’s advanced enough that when we have an idea we have the resources to run with it.”

At Micron, Barker says communication has been key to effectively supporting a culture of innovation. He advises getting feedback on issues that you may not have realised were relevant. For example, “we offer skills workshops for women engineers to develop skills that we assumed would be passed down in mentorship, but maybe haven’t been”.

Xerox’s Walker says in order for good internal communication to take place, it’s important that messages are coming from the top of the organisation that assure women that their concerns will be taken seriously.

Barker shares that the most useful way to foster innovation in his experience has been to demystify the internal invention review process, and explicitly encourage female inventors whose ideas have been rejected. Micron receives thousands of submissions per year, and many of them are not selected as something the company will invest in by applying for a patent.

“What we’ve found to be a critical success is having someone to mentor those engineers, to encourage them and give them some perspective on why it wasn’t successful”, says Barker. “When engineers get support from someone they view as a mentor, they persevere. Once women have success, we’ve seen that they’re more likely to succeed and invent in the future”. Promoting and running spotlights on these women serves to solidify the message that women can be inventors too, which in turn ripples out to inspire other women to innovate and get credit for their innovation.

Ongoing initiatives

As awareness around the importance and value of gender diversity in IP has grown, various action-oriented programmes have sprung up to target and improve specific metrics.

For example, Uber supports Girls Who Code, which aims to attract more girls to STEM fields.

ChIPs is an networking organisation for women in IP law, founded by women chiefs in IP (from Intuit, Apple, the USPTO, Atmel, Cadence Design Systems, eBay, and Cisco) in Silicon Valley.

Seven programmes – similarly focused on gender and IP – are profiled in the IWPR’s report, which was funded by Qualcomm. They are: Accelerating Women And underRepresented Entrepreneurs (AWARE), BioSTL’s Bioscience & Entrepreneurship Inclusion Initiative, Empowering Women In Technology Startups (EWITS), MyStartupXX, REACH for Commercialization, the US Department of Energy’s Phase 0 Assistance Program, and STEM to Market.

While they each have a unique focus, all of these programmes help women broaden their networks, obtain funding, meet mentors, and connect with guidance to help them with the patenting process. According to the IWPR report, leaders of these programmes stress the importance of identifying key gaps in existing supports, avoiding duplication of other efforts, and collecting data on outcomes.

Inspired by the IWPR’s research, the SUCCESS Act (Study of Underrepresented Classes Chasing Engineering and Science Success Act) was signed into law on October 31 2018.

It mandates the USPTO to conduct a study of the impact of the patent gaps in gender, race and veteran status on small businesses and entrepreneurship, and make recommendations to Congress for ways to close the gaps.

The jury is still out on the various initiatives described above as to which will be most impactful. What gets measured gets managed, but what are the key metrics to track and improve? Drinker Biddle’s Meyer says we have to attack the problem by constantly asking questions. She offers: Who are repeat inventors? Why are they getting it right? Are there groups doing a better job than others? Along the process from idea to market, where is the leakage occurring? Is it occurring in feedback to new inventors? Is it in access to the invention disclosure and review process? Is there bias in the invention disclosure review process? Do we need to provide more education to women on how to navigate the system?

Path forward

Kirkland’s Cendali is optimistic that progress for women in IP will continue full steam ahead. “When I started in the 80s”, she shares, “there weren’t any senior IP women partners, and there were very few women judges or heads of IP at companies. Over time, there has been a radical shift in acceptance of senior women attorneys. There are more women judges, which creates a more inclusive courtroom environment. Progress is always bumpy, but I’ve seen tremendous progress for both women and IP as a practice over time, and I’m hopeful it will continue”.

Progress won’t continue on its own, however. Johnson of Uber warns of burnout: “Time will not make things equal”, she says. “You need people to track the issue, and be committed to solving it. Women who experience the gaps in support should tell their stories and continue to speak about it.”

Thackray says it’s “heartening to see the legal industry paying real attention to not just recruitment, but also inclusion.” The focus on what can be done looks at what has been done, what didn’t work, and how we can make it work, “almost with an engineering mindset”, she explains.

Meyer adds: “I feel like Gene Kranz in Apollo 13, ‘Let’s work the problem people! Let’s not make the problem worse by guessing.’ Find the problematic algorithm, get rid of it, and try something different and new.”

“It takes a village”, says Thackray. “No-one programme solves everything, so you’ve got to have a multiplicity of efforts, and people in the majority motivated to help everyone feel included”. She acknowledges that IP is a particularly difficult field for women to feel included in because of the low numbers of women in STEM. Ever the optimist, she says that because of the growing appreciation of the value of diversity, “there’s never been a better time to be a woman in IP law”.

GENDER AND IP ANECDOTES

Mercedes Meyer, partner at Drinker Biddle in Washington, DC:

- An attorney went to an affinity meeting and gave her IP talk. Then a software engineer came up to her afterwards and said, ‘I have this idea, but I don’t know if it’s any good.’ They made an appointment and a patent application was filed. I asked the IP attorney if she thought that disclosure would have been made if she hadn’t spoken to the affinity group. In the IP attorney’s mind, the answer is no. She does not think the invention disclosure would have been made at all.

Angela Johnson, litigation counsel at Uber:

- I went through a stage at HP of questioning, is this really something I can do? I don't have a tech or hard science background. I had a great mentor at HP; Cynthia Bright also didn't have a tech background, but she was the head of litigation and absolutely inspiring. She told me I could do it if I rolled up my sleeves and read the case law. At the same time, I was usually the only black woman at various events. I had to develop my own confidence, and not be thrown off by that fact. I’ve litigated cases where they thought I was the court reporter. I relied on people who have done this before to talk things through with.

Dale Cendali, partner at Kirkland & Ellis in NYC:

- I never had a female mentor in IP or litigation. I was a pioneer in that sense, as a senior woman in the field. I did have an inspiring male mentor – Greg Joseph, one of the top litigators in the country – and he advised me not to just sit in my office and work, but to add more. ‘Do Bar work,’ he said, ‘and give speeches and write articles to give yourself credentials’. That way you become an expert by nature of doing these things, and people also know you.

Sandra Nowak, assistant chief IP counsel at 3M:

- I’ve been in the minority due to my gender, including college education in chemistry, doing chemical research for the government, and working in a large law firm’s IP department. Each of those had its own special challenges. When I got to 3M, I was thrilled to be in a large corporation where women were equally represented in the IP department, where the work was challenging and interesting, people were supportive and respectful, and where strong mentoring and coaching programmes exist at all levels and targeted toward all groups. Being in this environment has allowed me to really see the difference between the two settings and has caused me to become more passionate about helping to make more workplaces like this.

Gillian Thackray, Thermofisher, chief IP counsel:

- I got into this profession because I love science, but it was hard in the professional world. It was mostly men, and I was the only one who looked like me in the room. I got into IP law because a female IP attorney friend told me: ‘You could do this too, you should try it.’ It’s those champions who tell us to have faith in ourselves that matter most. Women resonate with that – we thrive on encouragement. Some women I’ve worked with have gotten discouraged and left the field. A friend of mine was a brilliant lawyer – Harvard grad – and she took two years off to have kids. When she tried to get back in the game, no one in the field would hire her. Someone should have taken a chance.