|

Peter Ollier: What are the main obstacles for companies seeking to obtain patent protection in your respective countries?

Participants |

|

|

Editha R Hechanova (EH) is a president/CEO of Hechanova & Co and managing partner of Hechanova Bugay & Vilchez lawyers in the Philippines |

|

Tan Tee Jim, SC (TTJ) is a senior partner of Lee & Lee in Singapore |

|

Dave A Wyatt (DW) is executive director and head of the patent and industrial design department at Henry Goh & Co in Malaysia |

|

Peter Ollier (PO) is Asia editor of Managing IP magazine |

Dave Wyatt: In terms of the administrative process, patent applicants are well-served by MyIPO these days, following its corporatisation in 2003. The formalities of the application and grant process are generally handled efficiently and expeditiously. The main obstacles for foreign applicants lie in their expectations of the substantive examination process, and unfamiliarity with how it operates. The Malaysian system is somewhere between independent examination and a system like that of Singapore, where one can rely wholly on foreign search/examination results.

Malaysian patent examiners normally follow the prosecution results of corresponding applications filed in Australia, the European Patent Office, the UK, Japan, the Republic of Korea, the US and under the PCT. An applicant that enters the national phase with a favourable PCT examination result, or that is prepared to adopt the allowed/granted claims of a counterpart application in one of those countries will usually be able to obtain grant without any problems. On the other hand, where an applicant wishes to pursue claims of a different scope, then considerable skill on the part of their Malaysian patent agent may be called for to persuade an examiner to allow such claims.

MyIPO has 80 patent examiners, as compared with about a dozen 10 years ago. Another issue that applicants (and agents) face is inconsistent practice by different examiners. More detailed examination guidelines, for example in contentious subject-matters such as software patents, may assist. However, this is a double-edged sword: the lack of detailed guidelines provides greater scope for arguing patentability on a case-by-case basis.

Editha Hechanova: There are no major obstacles in seeking patent protection in the Philippines. The Philippines is a member of the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) which took effect on August 17 2001. It became a first to file country since the IP Code (Republic Act no 8293) became effective on January 1 1998.

Possible obstacles include the fact that business methods and computer programs are not patentable. Computer related inventions, however, are patentable, but must comply with the requirements of novelty, inventive step and industrial applicability.

Patent examination can take a long time because of the lack of patent examiners at the Intellectual Property Office (IPOPHL). After 18 months from the Philippine filing, most applicants expect that substantive examination will start. However, from experience, it takes about a year after this 18-month period for an application to actually get assigned to an examiner.

Pharmaceutical patent applicants are confused about the amendments to the patent law in the Cheaper Medicines Act, particularly on whether second medical use is allowed. According to the Director General of the IP Office of the Philippines, it is allowed.

Tan Tee Jim: Apart from the costs involved in obtaining a patent (which can range between $6,000 and $15,000, if not more), the main obstacles relate to two of the pre-conditions for obtaining patent protection in Singapore, namely, novelty of the invention and inventive step (or obviousness).

Under our law, an invention is novel if it is not already known or made available to the public in Singapore or anywhere in the world. For many companies (particularly, small- and medium-sized companies), this requirement can be rather costly in terms of the searches to be carried out. Even if not, there would often be doubts and uncertainties as to whether their inventions can withstand objections or invalidity claims based on lack of novelty and/or obviousness. This is because a patent can be granted even if the patent search is not entirely clear.

The Philippines: Invention, utility model and design applications, 1998 |

|||||||||

Year |

Invention |

Utility model |

Industrial design |

||||||

Foreign |

Local |

Total |

Foreign |

Local |

Total |

Foreign |

Local |

Total |

|

1998 |

3280 |

163 |

3443 |

31 |

602 |

633 |

227 |

499 |

726 |

1999 |

3217 |

144 |

3361 |

41 |

606 |

647 |

252 |

515 |

767 |

2000 |

3482 |

154 |

3636 |

36 |

536 |

572 |

340 |

479 |

819 |

2001 |

2470 |

135 |

2605 |

21 |

426 |

447 |

316 |

382 |

698 |

2002 |

769 |

149 |

918 |

39 |

522 |

561 |

335 |

448 |

783 |

2003 |

1801 |

141 |

1942 |

21 |

477 |

498 |

343 |

667 |

1010 |

2004 |

2538 |

157 |

2695 |

19 |

573 |

592 |

476 |

536 |

1012 |

2005 |

2762 |

210 |

2972 |

27 |

519 |

546 |

619 |

646 |

1265 |

2006 |

3038 |

223 |

3261 |

22 |

519 |

541 |

486 |

475 |

961 |

2007 |

3248 |

225 |

3473 |

32 |

395 |

427 |

434 |

431 |

865 |

2008 |

3097 |

216 |

3313 |

33 |

512 |

545 |

581 |

640 |

1221 |

2009 |

2825 |

172 |

2997 |

48 |

496 |

544 |

320 |

458 |

778 |

2010 |

3224 |

167 |

3391 |

35 |

579 |

614 |

415 |

432 |

847 |

2011 |

1900 |

113 |

2013 |

27 |

371 |

398 |

349 |

337 |

686 |

Total |

37651 |

2369 |

40020 |

432 |

7133 |

7565 |

5493 |

6945 |

11752 |

94% |

6% |

100% |

6% |

94% |

100% |

41% |

59% |

100% |

|

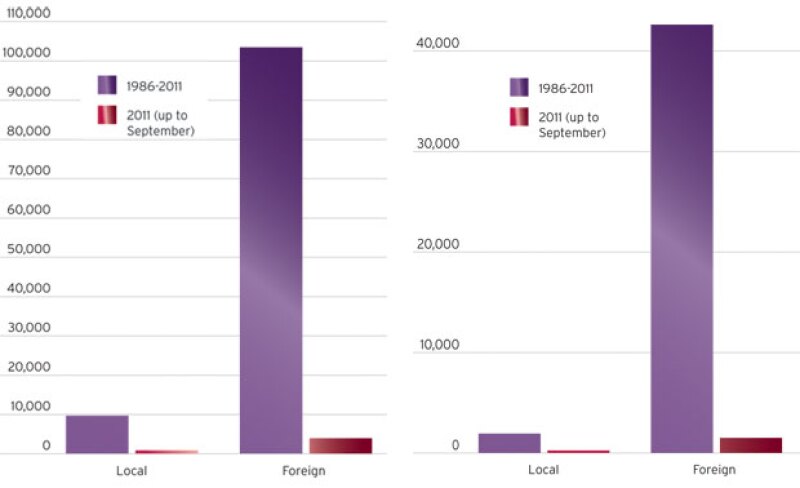

Malaysia: Share of patent applications by local and foreign applicants by year of filing (left) Malaysia: Share of granted patents by local and foreign applicants by year of grant (right) |

|

PO: What are the most recent patent filing trends? Are domestic and foreign applications increasing or decreasing?

EH: Statistics from IPOPHIL shows that since the IP Code took effect in 1998, invention patent filings for both domestic and foreign applicants have remained more or less constant. The average number of invention patent applications filed is about 2,900 annually, with foreign applications dominating at 94% and domestic applications at 6%. The same is true for utility models, except that the ratio is reversed with domestic filing at 94%, and foreign filings at 6%.

The number of applications for utility models is much lower, an average of about 540 applications a year, compared with invention patents. In the case of design patents or design registrations, the ratio between domestic and foreign filings is more or less even with domestic filings at 59% and foreign filings at 41%.

DW: The total number of patent applications filed in Malaysia has increased from 2008 to 2010, following our accession to the PCT in 2006. The numbers appear to be levelling off now. It looks like 2011’s total figure will be about the same as for 2010 – around 6,500. What is of particular interest is the growth in the number of applications filed by Malaysian applicants. This has increased year-by-year since 1997, though again the total number of local applications in 2011 appears to be levelling off and may be about the same as in 2010. Having said that, many applicants are now looking to global markets and may prefer to file a PCT application at the outset.

In 2011 (up to September), local applicants account for 18% of all applications, and 14% of all granted patents. The equivalent figures for the period 1986 to 2011 are 9% of applications and 4% of granted patents.

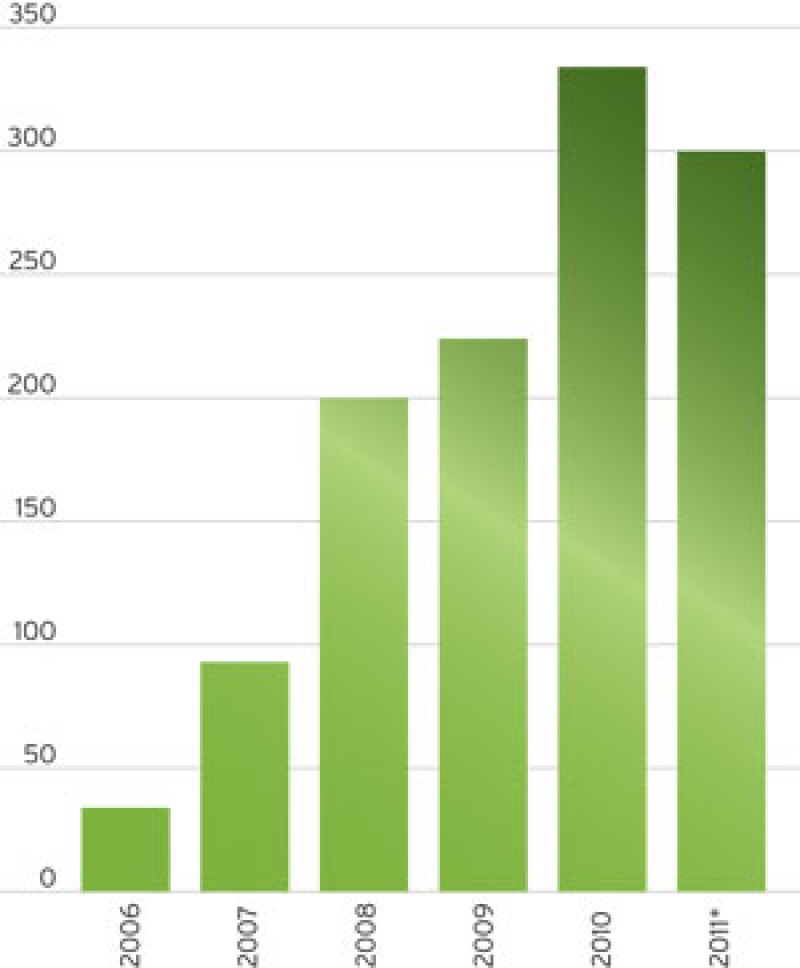

The number of PCT applications filed with MyIPO as receiving office has increased every year since we joined the PCT system in 2006. In 2011, the total figure is expected to be around 300 applications.

Malaysia: Trend of PCT applications filed |

|

TTJ: The most recent patent filing trends can be discerned from the following chart from the website of the Intellectual Property Office of Singapore (IPOS).

It is noticeable that the majority of patent applications in Singapore are made by foreign-based entities. Generally, there has been a marginal increase of domestic applications and a marginal decrease of foreign applications.

Have there been any important changes to patent laws or regulations in the last 12 months? Are any reforms planned?

TTJ: There have not been any important changes to patent laws or regulations in the last 12 months. We are not aware of any reforms planned. However, as a member of WIPO and WTO, Singapore undertakes reform of its patent laws and regulations when necessary, in keeping with its international obligations.

DW: Yes, a number of changes to the patent regulations were introduced in February 2011, as well as the first increase in official fees in over 10 years. The main changes are the introduction of a formal system of expedited examination, reduction in the period for requesting examination and a shortened term for responding to an office action.

In order to take advantage of expedited examination, an applicant must request examination in the normal way, and then submit a reasoned request for expedited examination and pay an official fee. If the request is approved, the applicant will be required to pay a substantial fee for the expedited examination. The grounds on which expedited examination can be requested are limited, and include: when infringement is taking place; when the applicant has already commercialised the invention or plans to do so within two years; and when the invention relates to green technology. Once expedited examination is under way, the applicant can expect to receive an office action within four weeks and must reply within a non-extendible term of three weeks.

As part of MyIPO’s further efforts to speed up the prosecution process, the period for requesting examination of a direct (non-PCT) application has been reduced from two years to 18 months from the filing date. The regular term for replying to an office action has also been shortened from three months to two months.

Whether these changes will really benefit many applicants remains to be seen. The official fee for expedited examination is significant and the use of the existing modified examination option will be more cost-effective and could be just as fast. The new period for requesting examination will not affect the majority of foreign applicants, since it does not apply to PCT national phase cases. The shortened term for responding to an office action is considered by the profession to be insufficient time and is less than available in most other countries.

Substantial further amendments to the Patents Act have also been proposed and drafted and are scheduled to be tabled in Parliament in 2012.

EH: There have been some changes in the rules relating to IP including patents. IPOPHL is encouraging alternative dispute resolution for both inter partes and administrative cases and in February 2011 issued rules governing mediation and arbitration. It has accredited mediators and arbitrators to handle said cases.

On January 1 2011, IPOPHL issued Office Order no 186 s 2011, amending the rules and regulations for administrative complaints, which include infringement cases involving patents, utility models and industrial designs. The amended rules removed the fixed period of 90 days for the writ of preliminary injunction, and the period is now at the discretion of the hearing officer. Also, the rules shall allow the payment of the bond required for provisional remedies, by surety bond instead of cash.

On July 17 2011, the rules on inter partes proceedings, which include cancellation of patents, utility models, industrial designs and layout of integrated circuits took effect (Office Order no 99 s 2011). The amendments are geared towards resolving these cases faster by disallowing the submission of certain pleadings once the answer has been filed.

On November 8 2011, the new IP rules for civil and criminal actions were issued by the Supreme Court. The rules cover also patent infringement cases. The important points are: the authorisation of the special commercial courts of the cities of Manila, Makati, Pasig and Quezon City to issue writs of seizure or search warrants with nationwide effect; shortening the litigation process by disallowing many pleadings and allowing the court to issue a decision based on position papers or conducting a trial; and allowing the destruction of infringing goods once the information or complaint has been filed, provided representative samples are set aside.

Amendments have been proposed to the implementing rules and regulations governing patents, utility models and industrial designs, and are awaiting approval by the director general. One example of a proposed amendment is making invention patent applications subject to prior use proceedings.

Singapore: Patent filing numbers |

|||

Year |

Number of applications by local-based entities |

Number of applications by foreign-based entities |

Total |

2010 |

892 (9%) |

8881 (91%) |

9773 |

2009 |

827 (9%) |

7909 (91%) |

8736 |

2008 |

808 (8%) |

8884 (92%) |

9692 |

2007 |

729 (7%) |

9226 (93%) |

9955 |

2006 |

626 (7%) |

8538 (93%) |

9164 |

2005 |

572 (7%) |

8033 (93%) |

8605 |

2004 |

641 (8%) |

7310 (92%) |

7951 |

2003 |

626 (8%) |

7282 (92%) |

7908 |

2002 |

624 (8%) |

7446 (92%) |

8070 |

2001 |

523 (6%) |

7610 (94%) |

8133 |

2000 |

516 (7%) |

7204 (93%) |

7720 |

1999 |

374 (6%) |

6305 (94%) |

6679 |

1998 |

311 (5%) |

6056 (95%) |

6367 |

1997 |

288 (5%) |

5760 (95%) |

6048 |

1996 |

224 (2%) |

12133 (98%) |

12357 |

1995 |

145 (6%) |

2267 (94%) |

2412 |

Which agencies or courts are responsible for patent enforcement procedures and how effective are they?

DW: Patent enforcement in Malaysia is done by way of civil action in the High Court. Patent infringement is not a criminal offence. In 2007, Malaysia started to introduce specialised IP Courts, with a plan for an IP High Court in each of the six states having the most IP disputes. Before this, civil cases involving IP were handled by the commercial division of the Kuala Lumpur High Court and heard by judges that lacked IP experience. Delays of four to eight years for cases to complete were typical. The introduction of specialised IP Courts in Malaysia with dedicated judges is certainly one of the most noteworthy and positive milestones on the IP scene in recent years. Although only the IP Court in Kuala Lumpur is active at present, IP cases are now given a much higher priority and can reach trial within 18 months or so. Many older cases that were transferred to this new Court have now been settled.

TTJ: The Supreme Court of Singapore and IPOS are responsible for patent enforcement procedures in Singapore. Both these bodies and the procedures are effective in enforcing patent protection.

EH: For administrative cases, the Bureau of Legal Affairs (BLA) of IPOPHIL has jurisdiction over patent cancellation and patent infringement cases. IPOPHIL has amended its rules on inter partes proceedings and also its rules of procedures for administrative cases, all geared towards speedier resolution of IP cases. The BLA has jurisdiction over administrative actions with claims for damages of not less than P200,000 ($4,600). For civil and criminal cases, the special commercial courts have jurisdiction over patent infringement cases and cancellation cases. Similarly, the Supreme Court, which supervises the special commercial courts, has issued new IPR Rules which took effect on November 8 2011, the objective of which is to reduce delays in IP litigation and make the anti-counterfeiting policy of the government stronger. The Bureau of Customs (BOC) prevents the entry of counterfeit and infringing goods through its recordation system, hence, patent holders can have their patents recorded with the BOC so the latter can watch for the entry of these infringing articles. The Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) through its regional offices all over the country has concurrent jurisdiction with the BLA over patent infringement cases. To avoid duplication, the DTI has an agreement with IPOPHIL that the DTI will handle IP administrative cases with claims of damages of less than P200,000.

Are there examples of recent cases where patent owners have effectively enforced their rights?

EH: There are very few patent cases being tried in the Philippines. The more recent ones ended in amicable settlement between the parties, for example, inter partes case no 11-2008-00024 for the cancellation of letters patent no 25960 in the name of Sanofi-Aventis covering the molecule Clopidogrel. In this case, petitioner Aldril Pharmaceutical and Sanofi Aventis entered into an amicable settlement of their dispute and the case for cancellation was dismissed.

DW: Yes, patent owners have fared well in some recent decisions from the Kuala Lumpur IP High Court. In three cases, the patent was upheld as valid, and in two of those cases infringement was found.

In SKB Shutters Manufacturing Sdn Bhd v Seng Kong Shutter Industries Sdn Bhd & Anor, SKB sued Seng Kong for infringement of SKB’s patent for a panel that can be interconnected with other panels to form a rolling door curtain of the kind used to cover and protect a shopfront. The defendant counterclaimed for the patent to be revoked on the ground of lack of novelty and inventive step. The attack on validity was rejected. The Judge favoured the testimony of SKB’s inventor, who explained the background to the invention and the problems he had addressed in the course of devising the invention. SKB’s inventor was considered to have the relevant common general knowledge of those in the roller shutter industry. The patent was thus upheld as valid, and the infringement pleading succeeded.

In Ranbaxy (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd v EI du Pont de Nemours and Company, Ranbaxy sought to invalidate two claims of the Du Pont’s Malaysian patent that covered potassium losartan in crystalline form, which can be used for treating hypertension and congestive heart failure. Ranbaxy also sought a declaration that it did not infringe those claims. The plaintiff had obtained regulatory approval in Malaysia to market a pharmaceutical containing potassium losartan. The defendant counterclaimed for infringement of one of the claims in dispute. Various attacks on validity were dismissed. The plaintiff was found to have infringed the patent and an injunction was ordered.

Finally, in B Braun Melsungen AG & Anor v Terumo Kabushiki Kaisha, B Braun’s patent for a safety intravenous catheter survived a counterclaim for invalidity. However, the patent claims were not infringed as three essential features of the claims were determined by the Judge to be missing in Terumo’s product.

TTJ: Yes. For instance, in Mühlbauer AG v Manufacturing Integration Technology Ltd [2010] 2 SLR 724, Mühlbauer succeeded in its action against the defendant for infringement of its patent for a Device for Inspecting and Rotating Electronic Components in relation to a machine for inspecting, picking up and placing electronic components onto printed circuit boards or tape and reel packaging. The defendant acknowledged that its device infringed the patent but claimed that Mühlbauer’s patent lacked novelty and was obvious in light of the prior art.

The patented device was used for inspecting, picking up and placing electronic components onto printed circuit boards or tape and reel packaging. With the patent, an optical inspection of a wafer chip, a pickup of a wafer chip, a turn-around and subsequent deposit of the wafer chip all occurred with a single 180 degree rotation of a two-headed pivoting part of the device. At the end of the 180-degree rotation, the device was primed to pick up the next wafer chip in line. Using a through opening located traversely between the two pickup heads, the top-mounted camera inspected the wafer chip below on the substrate while the pivoting part, picking up another wafer chip simultaneously, rotated through an angle of 90 or 270 degrees. As optical inspection and pickup were concurrent, the cycle time was reduced, resulting in greater productivity. The court held that the patented device was indeed novel.

In relation to the issue of obviousness, the court was of the view that the prior art “teaches away” from using two pickup heads only, as “there is a risk of the die flying off as a result of centrifugal force where two heads are used”. The prior patents all suggested using more than two pickup heads. In ruling that the patented device was not obvious in light of the prior art, the court said:

A patentee who contributes something new by showing that, contrary to the mistaken prejudice, the idea will work or is practical has shown something new. He has shown that an apparent ’lion in the path’ is merely a paper tiger. Then his contribution is novel and non-obvious and he deserves his patent.

In another case, First Currency Choice Pte Ltd v Main-Line Corporate Holdings Ltd [2008] 1 SLR(R) 335, the patent concerned an invention which provided an automatic means of determining the preferred currency for a card transaction between a local merchant and a foreign cardholder. The invention was more convenient to use and eliminated the frailties inherent in a manual system of currency conversion. The plaintiff who was the owner of the patent successfully sued the defendant who had offered for use a card currency recognition system that performed the same function as the plaintiff’s invention. The plaintiff also successfully resisted the defendant’s claims that the patent was obvious and that there was insufficient disclosure of the invention in the patent specification. In upholding the plaintiff’s action, the Court of Appeal said that one of the most significant issues in patent litigation is to determine the true construction of a patent specification and, in particular, its claims and that in determining the true construction, “the claims themselves are the principal determinant, while the description and other parts of the specification may assist in the construction of the claims”. In this regard, the court held that the starting point in patent construction is to ask the threshold question: what would the notional skilled person have understood the patent to mean by the use of the language of the claims?

The court said that, in determining this question, there was no necessity to expressly define and delve into who the notional skilled person might be in relation to the patent in question, as long as it is kept in mind the concept of the notional skilled person and who this person is in relation to the patent in question. The court rejected the defendant’s contention that the trial judge had failed to identify the notional skilled person and had not construed the claims in the patent from the perspective of the person and in the context of the common general knowledge of the art in question.

How can patent owners maximise their chances of success in the courts?

DW: From the stream of decisions that have been issued by the Kuala Lumpur IP High Court since its inception, a clear message emerges: the choice of expert witnesses has a significant bearing on the outcome of each case. Although we have dedicated IP judges, they do not normally have a technical background. The Court needs help on the technical issues that arise in every patent dispute.

As far as technical witnesses are concerned, patent owners need an expert whose knowledge of the field of the invention can be equated as far as possible with that of the fictional skilled person. At the same time, the expert must not be overly-qualified in terms of demonstrating inventive faculties. Presenting an expert that has these qualities and appears honest, impartial and objective to the judge will not in itself win a case. However, it will assist the Court in assuming the mantle of the person skilled in the relevant art, and thereby reaching a fair decision based on the facts.

EH: Most of the patent infringement cases were dismissed on the ground of lack of novelty, since the invalidity of the patent is always raised as defence. It is advised that a good prior art search be made when filing an infringement case.

TTJ: First, patent owners should know their own patents well. This involves assessing the strengths and weaknesses of their patents. Patent actions are often met by applications to invalidate the patents in suit. Before beginning actions, patent owners should review their patents to uncover possible weaknesses, errors and defects, such as in the patent specification.

Every patent owner should also know its opponent well. It should evaluate the opponent’s product to evaluate if its patent is indeed infringed by the product. It should also be familiar with any patent which the other side has, and assess the possible risk of a counterclaim for infringement and/or invalidation.

Lastly, patent owners should carefully choose their expert witness. An effective and convincing expert witness who is erudite and familiar with the relevant technology can be the difference between success and failure.

How much patent licensing is taking place at the moment in your jurisdiction? Are there laws in place to encourage and support technology transfer?

EH: There are no specific data on patent licensing. IPOPHL’s annual report states that an increase of 18% was noted in technology transfer agreements for 2010. The report showed that 204 applications for technology transfer agreements were received in 2010 involving the business/technical services sector, pharmaceutical industries, computer software, electronics/electrical appliances and parts. The IP Code provides for guidelines in technology transfer. In 2009, the Philippine Technology Transfer Act was promulgated. This Act aims to promote and facilitate the transfer and dissemination and effective use, management and commercialisation of IP technology and knowledge resulting from research and development funded by the government for the benefit of the national economy.

TTJ: IPOS does not have statistics on the extent of patent licensing in Singapore. However, there are laws in place that encourage and support technology transfer in the jurisdiction. For example, Singapore’s Patents Act provides that the exclusive licensee of a patent has the same right as the owner of the patent to bring proceedings in respect of any infringement of the patent committed after the date of the licence. It also allows the owner of a patent to make an entry in the register of patents so that the patent can be licensed as of right by an interested party. This helps the owner to attract licensees.

In addition, there are tax schemes in place which have the purpose and effect of encouraging and supporting technology transfer. For instance, reduction in or exemption from withholding tax may be granted in the case of royalty payments to non-residents made for purposes that will promote or enhance economic or technological development in Singapore. Also, companies can claim tax deductions of up to 400% subject to a cap of S$400,000 ($307,000) for activities such as R&D, IP registration and IP acquisition.

DW: Patent licensing activity is hard to assess as it is pretty much a hidden market. As a recent development, MyIPO’s online patent database now allows searching based on the name of the licensee. Patent licensing becomes visible when foreign patent owners launch infringement suits. Then, the plaintiffs will normally include a local subsidiary or other connected party as licensee. The extent to which there is licensing among Malaysian companies is certainly less than contracts involving foreign entities. Domestic patent licensing is nevertheless expected to grow as the proportion of local applicants and patent owners increases, and they seek to generate royalty income from their patents.

The Technology Acquisition Fund (TAF) that is administered by the Malaysian Technology Development Corporation assists Malaysian SMEs in the acquisition of foreign technologies for immediate incorporation in their manufacturing activity. TAF funding covers licensing-in of technology as well as its outright purchase and takes the form of partial grants.

What are the chances of further reform to harmonise patent practice within the different jurisdictions of the ASEAN region? What changes would need to be made?

DW: The patent offices of the ASEAN countries are more focused on improving their systems at a national level and the updating of IP laws has been driven by international agreements such as TRIPs rather than by regional ones. Cooperation efforts between these offices are based on sharing of work and information. An example is the Patent Prosecution Highway known as ASPEC (ASEAN Patent Examination Cooperation), which provides for the sharing of search and examination results among the patent offices of Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. An applicant that has had an application searched and examined in one of these countries may provide the search and examination reports to any of the other offices in order to assist and expedite the prosecution of a counterpart application.

ASPEC is one of the tangible outcomes of the 1995 Asean Framework Agreement on Intellectual Property Cooperation. However, it does not involve any changes to the national patent law in the ASEAN members. Harmonisation would require extensive changes in both the procedural rules (for example, filing date requirements, formal documents, term for requesting examination) and the substantive law (for example, novelty standards and grace period).

TTJ: The chances are not high, although there has been movement towards harmonisation. ASPEC could reduce search and examination duplication. It however remains to be seen whether the agreement will be implemented.

One important change that needs to be made is the enactment and harmonisation of patent laws in the different jurisdictions, thereby bringing the laws in line with international agreements on patents. There laws are quite diverse. Myanmar, for example, does not even have any specific patent legislation. Another ASEAN member, Laos, is not even a member of the TRIPs Agreement.

EH: There is certainly a chance of harmonising patent practice within the Asean region, but as to how fast these reforms can be made is difficult to predict, given the language differences.

From the army to IPOS – Singapore’s new IP head |

|

Tan Yih San, who took over as chief executive of the IP Office of Singapore in June, tells Peter Ollier about his plans for the office and how his time in the army has helped him prepare What plans does IPOS have in place to develop Singapore as an IP hub?We are studying our customers, a lot of whom are also our stakeholders. The market is telling us that we will have to continue to do a few things. First, strengthen our IP regime so that it is more business friendly. In some areas we need to shore up baseline awareness so that we can bring all people on board. This is especially true with SMEs, where we can equip them with the knowledge that they need to be able to capitalise on and exploit the IP that they have when they venture overseas. Of course we are also looking at making some of our services more customer-friendly so that we can serve customers in Singapore and can also reach out to our collaborators from overseas. What are the biggest challenges for IPOS over the next five years?There are many challenges. We have to seek out the trends and opportunities as well as the challenges in the economic sphere. I think the trade flow will continue but the directions will change. We are seeing more companies investing in this part of the world, especially from the United States and EU. There will be opportunities for companies to embrace some of this new investment. IPOS will try to assist our customers to better capitalise on these opportunities by improving our IP regime, improving information sharing and improving business practices. How do you help Singaporean companies register their IP overseas?We have put in place a Patent Prosecution Highway (PPH) arrangement with the USPTO and the JPO, and we are looking at building an architecture to facilitate more and more of these through the PPH channel to other markets including Europe and the BRIC countries. The PPH allows patent registration to be done in a much quicker and hopefully more efficient manner. With regards to trade marks we are already in Madrid and that suits everybody well. We will continue to support that. You have moved to IPOS from the army. What have been the biggest differences and similarities that you have noticed in moving to your new role?In the military I was dealing with innovation and emerging technology, so in some ways I was a user of IP. Now I am switching roles from being a user of IP to helping to build up the IP regime and that is a change. But I think that coming from the customer’s perspective gives me a better sense of how we can streamline our services to better serve our customers. In some ways it is a strength – when you hear representatives from industry you can empathise and imagine what the situation is on the ground. Visit managingip.com for more exclusive interviews with IP practitioners, judges, academics and officials |