|

Rumpus on the campus at GMU |

The Mercatus Center, which bills itself as “the world’s premier university source for market-oriented ideas” (AKA, a free market think tank), last month released a report titled “How Many Jobs Does Intellectual Property Create?” In it, the authors, Eli Dourado and Ian Robinson, pour scorn on estimates of IP’s effect on economic growth.

“In the past two years, a spate of misleading reports on intellectual property has sought to convince policymakers and the public that implausibly high proportion of US output and employment depend on expansive intellectual property (IP) rights,” it says. “These reports provide no theoretical or empirical evidence to support such a claim, but instead simply assume that the existence of intellectual property in an industry creates the jobs in that industry. We dispute the assumption that jobs in IP-intensive industries are necessarily IP-created jobs.”

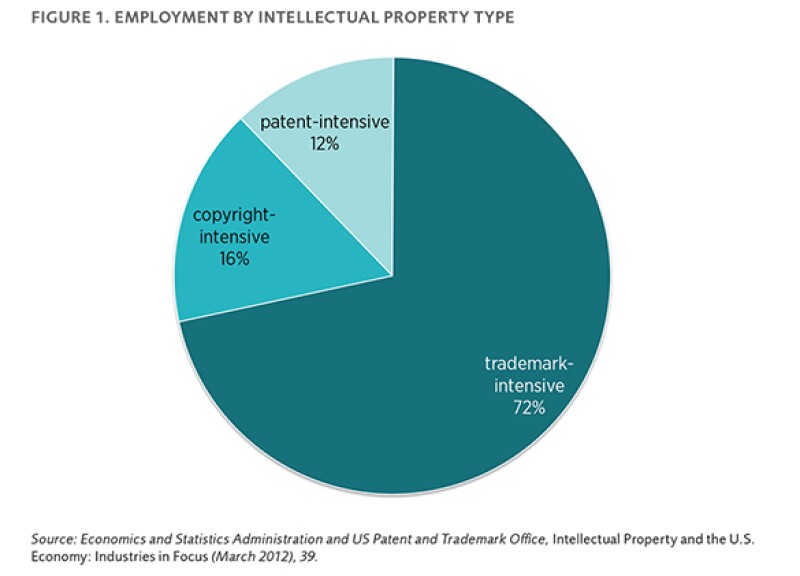

For instance, the authors call out a USPTO report from March 2012 that identified 75 “IP-intensive” industry groups that directly accounted for more than 27 million jobs and added more than $5 trillion in value to domestic product. The Mercatus authors argue that the claims are unsupported by any evidence linking job creation to intellectual property.

Where the report heads into stickier, more speculative ground is when it argues that “some of the jobs created by IP may harm the economy instead of helping it”. One reason offered for this is that consumers would spend more money on other products and services were it not for the higher expenditure on IP-intensive products.

|

Is Kickstarter a viable alternative to IP protection? |

They also point out that it is not the case that every job in IP-intensive industries would not exist but for the existence of IP. “The fact that an industry is IP-intensive, as defined by IPUSE, does not necessarily indicate that an industry’s output or employment is IP-dependent.” As an example, they say blogging does not rely on the copyrights that are automatically awarded.

Less persuasively, the report goes on to say IP is not the only way to incentivise creation and invention. “Prizes and awards can stimulate production of new innovations or creative works,” the report says. It adds that assurance contracts such as those enabled by crowdfunding platform Kickstarter are another way creation can be awarded.

“An odd report”

Mark Schultz and Adam Mossoff at the Center for the Projection of Intellectual Property (CPIP) at George Mason University have hit back. Rather than walking around the corner to the Mercatus Center and having it out in person, they wrote an article on Tech Policy Daily’s website and a follow-up post on their website in which they outline their disagreements. In the Tech Policy Daily article they begin with the obligatory-among-IP-proponents hat tip to the nation’s Founders, before going on to concede that there is “certainly a lot of empirical research to challenge”. The first problem with the Mercatus report, they say, is that it mischaracterises the studies they are attacking.

Schultz and Mossoff point out that the reports savaged by Mercatus make “far more modest claims than the report suggests”. Rather than claiming IP creates all the jobs in the industries identified as IP intensive, they merely develop a method for identifying these industries and then describe the contribution of these industries to employment and economic output.

Schultz and Mossoff say it is perfectly valid to try to understand IP’s importance by looking at the economic contribution of IP-intensive industries. “Additionally, it is hard to dispute that IP creates some jobs – most likely a lot of jobs – in America, given the size and importance of its innovation and creative industries.”

|

Pie in the sky? The USPTO's report on jobs in IP |

They point out that the US and Great Britain seemed to do just fine in the past 200 years when it came to balancing IP rights and economic innovation.

One of their biggest problems Schultz and Mossoff have with the Mercatus authors is they do not back up their claims that the US would enjoy even greater prosperity with weaker IP protections with any empirical evidence of their own.

“Apparently, the authors of the Mercatus report presume that the burden of proof is entirely on the proponents of IP, and that a bit of hand waving using abstract economic concepts and generalised theory is enough to defeat arguments supported by empirical data and plausible methodology,” say Schultz and Mossoff in their article on the CPIP website.

Noting that “you can’t beat something with nothing”, Schultz and Mossoff challenge IP sceptics to stop making “faux originalist arguments” and offer some evidence.

They also give short shrift to some of the alternatives offered by the Mercatus report, especially the idea that prizes, Kickstarter, government funding, or patrons can take the place of IP.

“But none of these alternatives is problem-free,” say Schultz and Mossoff in the Tech Policy Daily piece. “It is bewildering, for example, to find a libertarian think tank arguing that government projects are superior to private property rights as a means of directing resources to innovative activities. While prize systems may seem innocuous, they also have a historical legacy that should make free market advocates blanche, such as political logrolling and rent-seeking machinations that denied actual innovation due recognition and support.”

These are all good points in an argument that will never be won by either side. Which side are you on?