In the 2023 financial year, as reported by Development Bank of Singapore (DBS) Limited, India’s software exports reached a record high of USD $320 billion, and India’s total share in global computer services exports increased to about 11%..

This surge in software exports was primarily driven by the invigorated research and commercial interest in the development of artificial intelligence (AI)-based software, particularly in the field of computers, information technology, image processing, and telecommunications. The growth in such AI-based software production was also due to the advancement in machine learning, increased access to big data, and improvements in computing hardware.

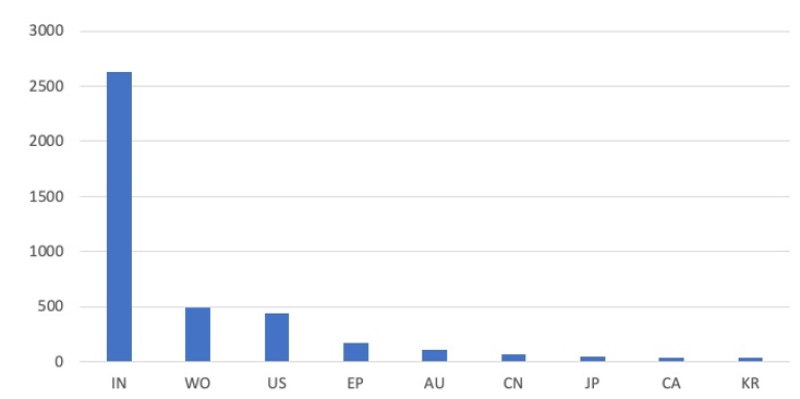

The rising tide of AI-based software applications is profoundly transforming the landscape of technology development in the country. The capacity of algorithms to optimise and automate increasingly complex tasks has led to a surge in productivity in some traditional industries and radical disruption in others. The result of this is new industrial activity and innovation, occurring on a scale that has a direct and measurable impact on patent filings too. The following chart shows a positive trend of increased patent filings at the Indian Patent Office (IPO) for AI-related inventions.

Indians filing AI patents in various countries

Image courtesy: https://brainiac.co.in/artificial-intelligence-and-patenting-in-india.

The patentability of computer-implemented and AI inventions

Not only in India but also in other parts of the world, the increase in patent filings related to CRI (computer related inventions) and AI has prompted several patent offices to revisit their respective patentability requirements of software. The primary reason for this being that these inventions fall within the ambit of excluded subject matter.

For example, at the most basic level, software code instructs the AI system to perform actions, make decisions, and determine outputs based on pre-existing commands, such as “if a condition is true, then [perform the following action].” Once many such commands are aggregated into a computer programme, the software can provide outputs without further instruction when the AI system is provided with data as the input.

Therefore, the bigger question is how to examine patent applications of inventions related to CRI and AI. Like any inventions, CRIs and AI inventions must meet the fundamental legal requirements of novelty, inventive step, and industrial application to be patentable. The IPO does not positively define what an invention is; rather it provides a non-exhaustive list of “non-inventions”, defining subject matter and activities that are excluded from patentability to the extent that they relate to the subject matter as given under Section 3(k) and 3(m) of the Indian Patents Act, 1970:

Section 3(k): “a mathematical or business method or a computer programme per se or algorithms”; and

Section 3(m): “a mere scheme or rule or method of performing mental acts or a method of playing a game”.

In practice, the test to determine whether the subject matter defined in the claims of a patent application is considered an invention, requires demonstrating the presence of any “technical contribution” and “technical effect” in the claimed subject matter.

This has been once again reasserted by the Hon’ble Delhi High Court (DHC) in Microsoft Technology Licensing, LLC Vs The Assistant Controller Of Patents And Designs, C.A.(COMM.IPD-PAT) 29/2022:

“The Court would thus reinforce the views expressed in Ferid Allani (supra) concerning the meaning of the term “computer program per se” in Section 3(k) of the Act. The patent applications should be considered in the context of established judicial precedents, Section 3(k) of the Act, extant guidelines related to CRIs, and other materials that indicate the legislative framework.

“If a computer-based invention provides a technical effect or contribution, it may still be patentable. The technical effect or contribution can be demonstrated by showing that the invention solves a technical problem, enhances a technical process, or has some other technical benefit. The mere fact that an invention involves a mathematical or computer-based method does not automatically exclude it from being patentable. The invention can still satisfy the patentability requirements, including the requirement for a technical effect or contribution, to be eligible for patent protection. In other words, method claims in computer programme patents may be patentable if it involves a technical advancement and provides a technical solution to a technical problem and has an improved technical effect on the underlying software.”

What is “technical”?

To identify a technical contribution and technical effect, let’s understand what “technical” means for a CRI invention. Inventions demonstrating some kind of positive effect on the resources of the device, such as reducing memory use or processing time, optimising the use of the display area or providing higher security, would be considered as being technical in nature. If the system involves some kind of communication between one or more devices, this feature would also be considered as being technical, as it would result in achieving a similar kind of positive effect on the resources of the device.

The same has been further illustrated by the Hon’ble DHC in Ferid Allani vs UoI, W.P.(C) 7/2014 & CM APPL. 40736/2019:

“Technical effect

It is defined for the purpose of these guidelines as solution to a technical problem, which the invention taken as a whole, tends to overcome. A few general examples of technical effect are as follows:

Higher speed;

Reduced hard-disk access time;

More economical use of memory;

More efficient data base search strategies;

More effective data compression techniques;

Improved use interface;

Better control of a robotic arm; and

Improved reception/transmission of a radio signal.

Technical advancement

It is defined for the purpose of these guidelines as contribution to the state of art in any field of technology. It is important to divide between software, which has a technical outcome, and that which doesn’t, while assessing technical advance of the invention. Technical advancement comes with technical effect, but all technical effects may or may not result in technical advancement.”

In view of the above understanding, let’s consider the eligibility framework for the three fundamental layers which are prime to the implementation of an AI invention:

Data layer;

Application layer (i.e., software); and

(3) System layer (i.e., hardware).

The data layer is not discussed in detail, as it is mainly about collecting and processing data, and the data itself is not technical in nature. Moving on to the application layer, if the claims define purely an implementation of an application layer (e.g., mathematical subject matter), then they fall under the exclusion. For example, a claim only defining “a method of classification using machine learning” is considered abstract, i.e., non-technical, and would be excluded.

Similarly, phrases such as “deep learning”, “artificial neural network” and “support vector machine” are considered to define abstract entities that would fall under the exclusion, if claimed as such. However, if a claim defines technical means related to the system layer, it will not be considered to define excluded subject matter “as such”. To be considered eligible, the claimed subject matter should therefore demonstrate “technical contribution” and “technical effect”. Unlike in Europe, the mere reference to a physical system, for example a “method implemented on a computer” would not give the claim a sufficient technical basis to pass the eligibility test.

In a simpler example, a user might input the data of the temperature on January 1 in New York City for the past 100 years. Pre-written software might then perform a series of instructions (add all temperature values and divide them by the number of values) to determine the average temperature in New York City on January 1. More sophisticated software forecast models might consider many other data variables, such as recent weather trends, average temperatures the week before the data at issue, the temperatures in nearby locations, user-generated weather data, wind patterns, etc. But at its core, such an AI system receives data and uses pre-written software commands to analyse information and provide a desired output to the user.

More sophisticated computational models allow AI to “learn” (“The Role of Patent (In)Eligibility in promoting Artificial Intelligence Innovation”, Nikola Datzov, University of North Dakota School of Law). For example, “machine learning” allows an AI system to “sort through massive amounts of data, recognise patterns in the data, and then repeatedly adjust its search to get more precision about those patterns.” A “deep learning” model allows AI to search “data in increasing layers of abstraction without human engagement,” and AI “neural networks” rely on “mathematical modelling aimed at copying natural neural networks.” Both can create much more sophisticated systems capable of driving decisions and analysing information.

The final layer—the system layer—is the layer most people are likely familiar with. It is the layer of an AI system that runs the software, receives inputs, interacts with a user, and displays outputs. It is the user-facing layer. In the simple example above, it is the generic computer hardware that allows the system to function. It includes the processor, memory, power supply, motherboard, keyboard/mouse (or other input device), and the monitor (or other output device). In other examples, the systems layer might be the microphone that allows voice activated commands or the fingerprint scanner that unlocks a door or device. Or it may be the humanoid robot that can walk, talk, and perform various activities. Simply put, it is the tangible, physical system as part of which the AI can function.

Therefore, understanding the technical contribution made by a mathematical method implemented by AI, requires considering whether the method, in the context of the invention, serves a specific technical purpose. A generic purpose such as “controlling a technical system” is not sufficient to confer a technical character to the mathematical method.

Moreover, the patent claim must be functionally limited to the specific technical purpose, either explicitly or implicitly. This can be achieved by establishing a sufficient link between the technical purpose and the mathematical method steps. For example: specifying how the input and the output of the sequence of mathematical steps relate to the specific technical purpose so that the mathematical method is causally linked to a technical effect.

Further, during the training process, the training algorithm (also known as the optimisation algorithm) optimises weights (trainable parameters) when trainable data sets are fed into the AI model for the machine learning process. The better the quantity, quality, and variety of the training data, the more accurate the computation of the trainable parameters will be, leading to a more precise output. In simpler terms, the quality of the AI model comprising the model architecture, training algorithm, and training data, influences the accuracy of the output. By feeding the AI model more data, the whole architecture becomes more experienced, thereby producing a better and unpredictable output.

Hence, it is important that the feature(s) of AI, which fall under the exclusions, are integrated into a practical application. The evaluation of patentability will require more additional elements in the claims that amount to an inventive concept, instead of just the recited judicial exclusions. If the overall claim amounts to significantly more than the exclusion itself (i.e., there is an inventive concept in the claim), the claim includes patent eligible subject matter.

Conclusion

To continue fostering the growth of AI-related inventions in the country it is important to define a patent eligibility framework for such inventions. The framework should provide a clear and definitive empirical determination of “technical contribution” and “technical effect” regarding the patent eligibility of AI-related inventions. The rapidly evolving nature of technology also poses a challenge, as what constitutes a technical effect or technical contribution may become outdated in future. Therefore, there is a pressing need to clarify these concepts to strike a balance between protecting the rights of inventors and promoting the public interest and social welfare.

The same was also opined by the Hon’ble DHC in Microsoft Corp. vs Asst. Controller of Patents, that this can be achieved by providing examples or illustrations of patentable and non-patentable computer related inventions. The need of the hour is that along with CRIs, the IPO may also consider providing eligible and non-eligible examples of AI-related inventions. There are presently no signposts for the examiners to navigate the field of examination of CRIs and AI related inventions, thus potentially leading to inconsistency in the examination of such inventions.