IP filings are rising

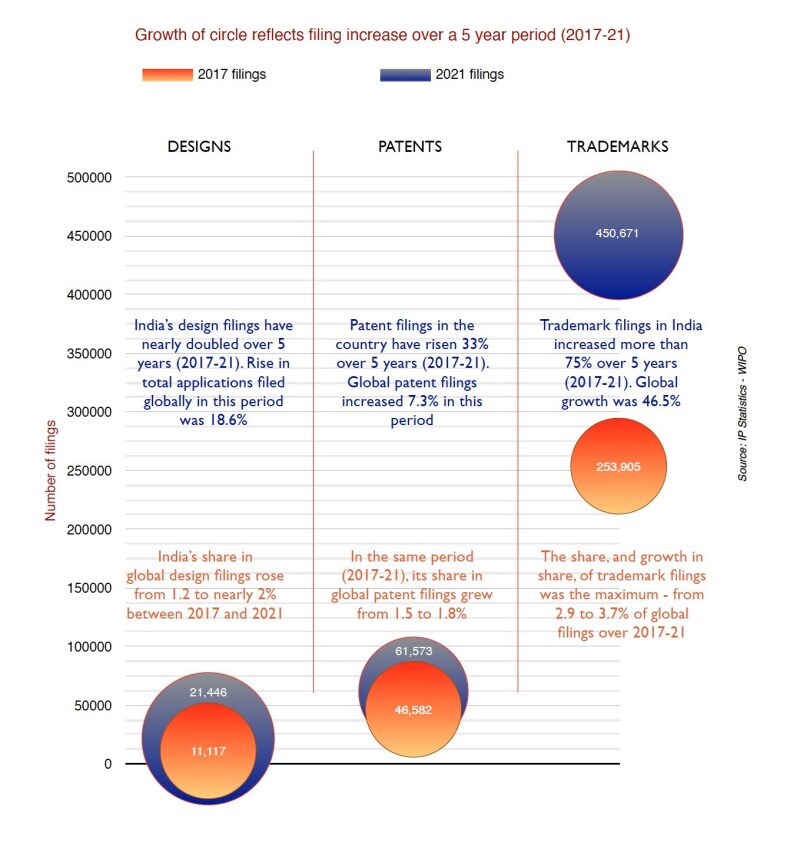

Intellectual property (IP) filings in India have surged significantly in recent years. In statistics released by WIPO in 2022, India ranked fifth in terms of the number of trademark applications filed annually and sixth in the world for patent filings. Notably, the growth in Indian filings is consistently higher than global averages. See Figure 1 below.

A dynamic ecosystem

In May 2023, World Trademark Review reported that global trademark filings fell 17% in 2022. Among the five major jurisdictions in Asia and Oceania – Australia, China, India, Japan and South Korea – India was the only country in which trademark filings increased in 2022.

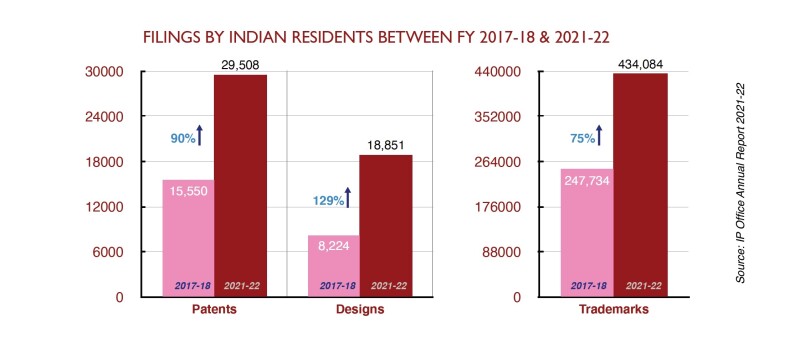

A rapid increase in resident filings is propelling the growth of IP filings in India. Figures 2 and 3 below capture statistics over a five-year period (FY 2017–18 to 2021–22). In the same period, non-resident patent filings grew 14.3%. Trademark and design non-resident filings remained static.

India’s maturing innovation climate is reflected in its ranking in the Global Innovation Index (GII), which has improved from 60 to 40 between 2017 and 2022. In terms of innovation performance, it is the top economy in the ‘Central and Southern Asian’ region and the ‘Lower Middle Income’ group of countries.

India ranked fourth globally (following the US, China and the UK) in venture capital investments in 2022, recording $24.1 billion, as tech investors worldwide continued to invest in the country’s tech firms despite a challenging macroeconomic climate. And for the second year in a row, India overtook China by adding 23 unicorns in 2022, while the latter created 11 such start-ups with a valuation of $1 billion or more.

Trademarks are a good proxy for the introduction of new goods and services in the market, and the creation of new companies. Per the GII 2022, an analysis of keywords listed in the description of trademark applications reveals that growth in India is driven by new goods and services that rely on digital business models, fostered by the pandemic’s disruptions and the accelerated adoption of digital technologies.

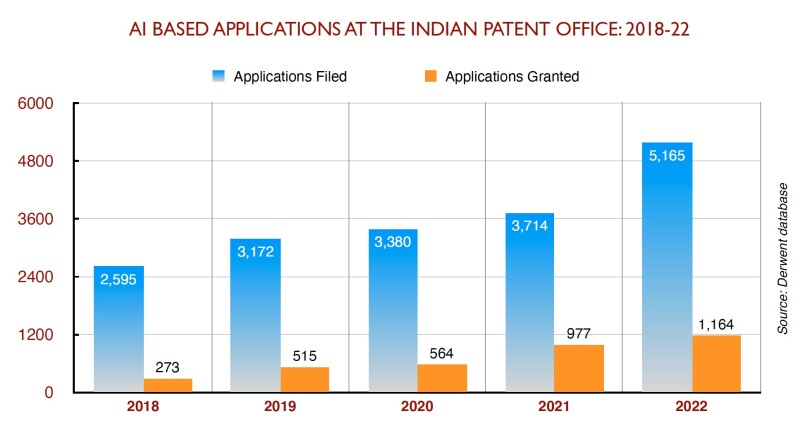

With regard to artificial intelligence (AI) and related applications, the Stanford AI Index Report 2023 ranks Indians third in terms of being positive about accepting AI technologies and their benefits. The report also states that the share of Indian publications in AI journals increased from 1.3% in 2020 to 5.6% in 2021. Private and public entities are jumping on the AI bandwagon. Some of the varied areas where the Indian government has started using AI technologies are tax compliance, climate-smart farming practices and traffic management.

Between 2018 and 2022, the number of AI-based applications filed at the Indian Patent Office nearly doubled. Figure 3 below shows how quickly AI patents are gathering momentum.

The government is proactively taking measures to align Indian IP laws with fast-paced advancements in AI technology. The Parliamentary Standing Committee on Commerce, in its report on India’s IP rights regime, has recommended several changes, including a review of Section 3(k) of the Indian Patents Act, 1970, which bars the patenting of algorithms. The committee referred to the position at the EPO and in the US, where mathematical methods and algorithms can be patented in certain situations, such as linkage with tangible technical devices or implementation in practical applications.

With changes in the pipeline, India is progressing towards a more tech-conducive environment.

Performance of the Indian IP office

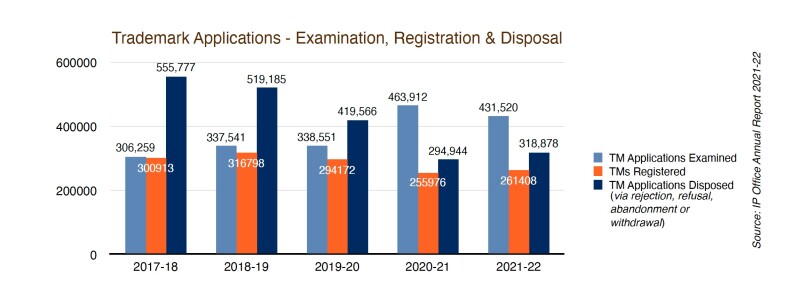

Figures 4 and 5 below illustrate the pace of the trademark office’s functioning.

The trademark office has seen vast improvements in the past decade in terms of efficiency, transparency and consistency in decision making. Many drives have been undertaken to clear backlogs. The spikes in disposal figures in 2017–19 in Figure 4 above can be attributed to such drives. And though the data for 2021–22 reveals a slight fall in examinations (despite an increase in filings), an application which does not encounter substantive objections from the registrar, and is not opposed by a third party, can expect to go through to registration within 8–10 months of filing.

Pendency is more of a worrying factor with regard to trademark oppositions. As at March 2022, more than 225,000 opposition cases were pending before the five trademark offices in India. Among these matters, a large number awaited the appointment of hearings, and inadequate manpower was revealed to be the chief reason for the delays.

The High Court of Delhi subsequently directed the Indian IP office to table a proposal on resolving the backlog, putting on record annual details of all pending opposition matters, including their stage of pendency. Progress reports submitted to the court have indicated a revised strength of 59 hearing officers at the end of 2022 and a plan to recruit 250 new hearing officers in 2023.

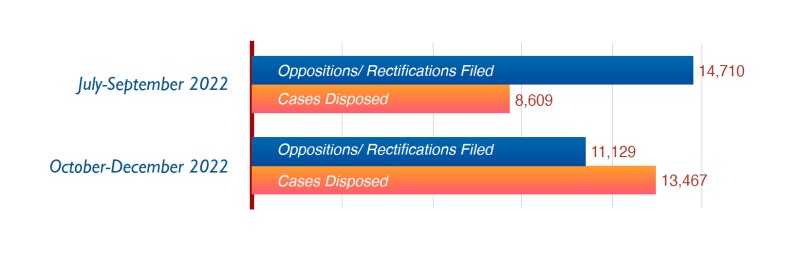

In January 2023, the figures released for the disposal of opposition cases between July and December 2022 showed improvement. See Figure 5 below.

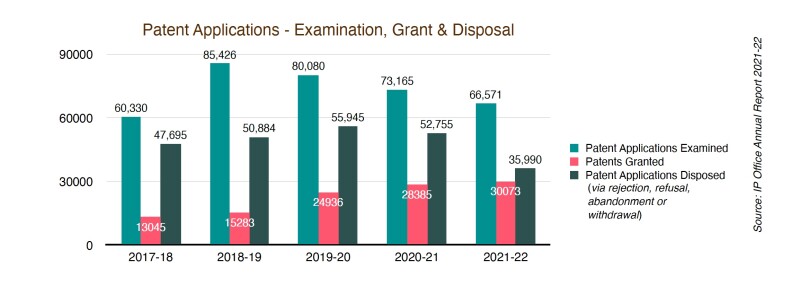

Figure 6 below reveals the pace of the Indian Patent Office’s functioning.

In 2021–22, the disposal of 15,991 applications was impacted by the extension of the limitation period granted by the Supreme Court on account of the pandemic. Overall, the Indian Patent Office has been ramping up its capacity to process patent applications, particularly as filings in India are expected to register strong increases as patents become increasingly central to business strategy.

The time taken from the point of filing a patent application to the issuance of a first office action has decreased from 18 months in 2020 to 4.8 months, which is the fastest in the world. But final outcomes still face delays – the average time for disposal stands at 58 months.

An augmentation in staff strength, which is on the anvil, will prove key in improving timelines. In a 2022 report, India’s Economic Advisory Council suggested that the manpower at the Indian Patent Office needs to increase from about 860 to 2,800 in the next two years.