Obtaining evidence has long been acknowledged as one arduous task for patentees seeking to take legal actions in China. The fact that plaintiff bears greater burden of proof in judicial proceedings in China has drawn criticism from the legal community. The matter is further complicated by the lack of discovery procedure and the high bar set for admissibility of evidence.

Evidence on the infringing product/process

Notarised purchase

Courts in China have set high bar for the assessment of the authenticity of evidence. It is practically impossible for Chinese courts to rely purely on witness affidavit. Documentary evidence is the most popular and frequently adduced evidence in China.

Under most circumstances, notarisation is recommended in preservation of key evidence, given the notarisation process will lend further credence to the evidence. Therefore, patentee usually resorts to notarised purchase when gathering evidence on the infringing product/process.

The typical procedure is to purchase the accused product (often by the patentee or its proxy) directly from the infringer (manufacturer or distributor) under the witness of notary public. The infringing products will be packed and sealed by the notary public for court inspection at a later date (usually at the hearing).

Generally speaking, if the infringing product is consumer goods, the right holder could make a purchase as an anonymous consumer under the witness of notary public. Conversely, the difficulty for the notarised purchase of infringing products designed for industry use will increase significantly. The reason is simple – the infringer would want to vet the identity of the buyer, especially in an industry with a small number of players.

Patentees will have to disguise their true identities and pose as trustworthy buyers. It could take the patentee some time to build trust with the infringer before the latter lets down his guard and sells the infringing product.

Legitimacy issue under procedural law

Technically speaking, notarised purchase is not risk-free under procedural law. After all, the infringer could challenge the legitimacy of the evidence gathered from the notarised purchase, contending that the right holder fabricated an identity and tricked the infringer into selling the infringing product.

Fortunately, China’s Supreme People’s Court (SPC) affirmed the legitimacy of the approach in an exemplary case Founder v Gaoshu [(2006) Min San Ti No.1] in 2006. The principle observed in this case has been widely followed since then.

The plaintiff, Founder is the copyright owner over a set of software. The defendant, Gaoshu secretly duplicated and sold the pirated software to quite a few customers. To obtain evidence, an employee of Founder posed as a customer and approached Gaoshu, using a bogus name, to purchase the pirated software.

The employee first purchased some hardware product to gain the defendant’s trust and then asked the defendant whether they provided pirated software. After receiving a positive answer, the parties signed sales contract and the defendant installed the pirated software on the buyer’s computers as per his request. The transaction and software installation process were witnessed by the notary public, without divulging their true identities throughout the process.

In the ensuing litigation, the defendant argued that Founder tricked their salesperson into selling the pirated software, because their standard offer would be genuine software, it was Founder’s employee specifically requested pirated software. The evidence collection approach is therefore illegal and the evidence shall not be admitted by court. The opinion of the trial court and that of the court of appeal diverged greatly on the legitimacy of the approach and the case was later petitioned to the SPC for re-trial.

The SPC allowed the aforesaid evidence collection approach: “Despite the fact that laws have expressly stipulated offences, more often than not, due to the breadth of social life and complexity of interests at stake, laws tend to establish legal principles, rather than provide an exhaustive list of offences, so that judges may exercise discretion by weighing interest and taking into account value orientation.

Therefore, regarding an act that is not expressly prohibited by laws and regulations, whether such act is detrimental to public interest shall be assessed based on its substantive fairness. The notarised approach Founder employed in evidence collection is not unjustified in terms of its objective and the acts did not harm public interest or others’ legitimate interests.

In addition, considering that computer software infringement is often covert and relevant evidence is difficult to gather, the approach employed by Founder is conducive to overcoming the difficulty in evidence collection, deterring potential infringers and ramping up intellectual property protection. The approach shall be deemed as legitimate and valid, and the evidence gathered shall be found admissible in ascertaining the facts of the case.”

Alternative evidence collection approaches

In case it is impossible for the plaintiff to gather evidence of his own accord, the plaintiff may seek assistance from the court. Courts may, upon the plaintiff’s request, investigate and gather evidence on the accused product/process.

To serve that purpose, plaintiff needs to produce prima facie evidence to substantiate the infringement, adducing evidence showing the whereabouts of the accused product or product line and submitting a written statement, elaborating on the urgency of gathering evidence and the hindrance keeping the plaintiff from obtaining evidence of his own accord. With or without a pre-litigation hearing to listen to plaintiff’s grounds, court will decide whether the prima facie evidence merits the granting of the plaintiff’s evidence collection request and to what extent the plaintiff’s burden of proof is to be alleviated.

In Henglian v Changyi [(2013) Min Shen Zi No. 309], the patent at issue concerns a type of paper manufacturing process, for which the plaintiff is unable to produce notarised evidence. Plaintiff thus requested the court to gather evidence. To make a strong case, the plaintiff produced a video record of the defendant’s product line as preliminary evidence and the request was granted. When the judges went to the defendant’s factory to preserve evidence, they were deliberately led by the defendant to the wrong product line. The trial court ordered the defendant to disclose the manufacturing process, but to no avail. The court thus found infringement based on the plaintiff’s preliminary evidence.

The lower court’s decision was upheld by the SPC, affirming that courts may shift the burden of proof to the defendant, provided that the plaintiff has proved the accused product is identical with that produced by the process patent at issue, and the plaintiff has made every effort to gather evidence, based on common sense and life experience, judges may conclude it is highly likely that infringement can be established.

In practice, courts may also designate other parties to gather evidence. By issuing court order, courts may authorise lawyers to gather evidence by asking the parties to hand over evidence in their possession. Such court order rarely applies when the plaintiff needs to collect the infringing product/process from recalcitrant infringer. Nevertheless, the approach is being widely used in the scenarios where the evidence is controlled by government agencies or the third-party companies (like e-commerce platforms).

Evidence on the calculation of damages

Parameters in determination of damages

In China, damages may be calculated by the following methods: i) actual losses incurred to the right holder; ii) illegal proceeds acquired by the infringer; or iii) reasonable multiple of patent royalties.

Where it is difficult to ascertain damages by the aforesaid three approaches, the court may resort to statutory damages and determine at its discretion the amount of damages ranging from RMB30,000 to RMB5 million.

In practice, right holders often opt to calculate the illegal proceeds acquired by the infringer, or statutory damages substantiated by proof of infringer’s illegal proceeds, which is calculated based on the below formula:

Infringer’s illegal proceeds

=

Turnover of the infringing product

×

Operational profit margin of the infringing product

×

Patent contribution rate to the profit

The question is – without discovery procedure, how could the right holder find evidence of infringer’s profit? In practice, right holders may find sales price of the infringing products, bits and pieces of sales figures through public channel and maybe the average profit of the infringer if they get lucky, but not a chance when it comes to the infringer’s profit margin of the specific infringing product nor the patent contribution rate to the profit. The most direct evidence – the infringer’s transaction record of the infringing product- is usually under the infringer’s control and out of the reach of the patentee.

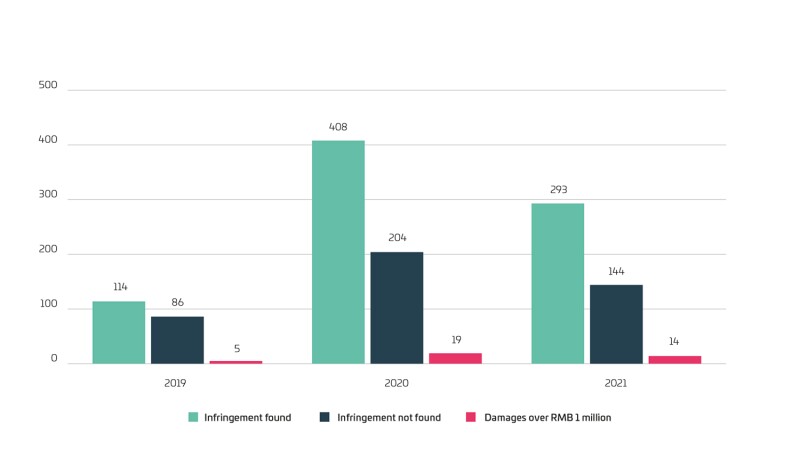

Figure 1 shows the outcome and number of cases with damages over RMB 1 million (inclusive) of all the published patent civil decisions (available at https://www.iphouse.cn/) made by the Intellectual Property Court of the Supreme People’s Court (the SPC IP Court), the sole appellate court for patent infringement litigation since 2019. Of all the cases where infringement could be established, those with over one million damages accounts for 4.4% in 2019. The percentage rises slightly to 4.7% in 2020 and 4.8% in 2021, which means securing high damages has yet become less onerous in China.

Figure 1: Patent civil appeals adjudged by SPC IP Court - Outcome & Indemnity ≥ RMB 1 million

High damages

The fourth amendment of China’s Patent Law, which comes into effect as of June 1 2021, incorporates into law (Article 71.4) the possibility of shifting burden of proof to the defendant, mandating that the defendant is to produce the account books related to the accused product, if the patentee has made best efforts to adduce evidence whilst the financial books or materials related to the infringement are controlled by the infringer.

Noncompliance may result in the court’s award of damages by reference to the claims and the evidence provided by the patentee. The case below is a live example of the application of Article 71.4.

In Synthes GmbH v Double Medical [(2021) Zui Gao Fa Zhi Min Zhong No. 148] the SPC IP Court awarded the plaintiff RMB 20 million ($3.2 million) by admitting the plaintiff’s evidence and shifting burden of proof to the defendant.

The plaintiff Synthes owns a patent concerning a medical device for the treatment of femoral fractures. The defendant Double Medical, which is a listed medical device company, was sued by Synthes for patent infringement. Synthes sought damages of RMB 20 million. The court of first instance only awarded damages of RMB 1 million. Both parties appealed to the SPC IP Court.

To prove defendants’ illegal profit, Synthes collected preliminary evidence about the defendant’s turnover of the accused product, including defendant’s online sales figure of the accused product for about 42 days and defendant’s revenue as disclosed by its financial report, based on which Synthes deduced that the turnover of the accused product reached RMB 39.74 million.

Though the defendant also published its overall operational profit margin (53%) in the financial report, this rate does not specifically correspond to the accused product. Given that Synthes had fulfilled its burden of proof, the court ordered the defendant to produce the account books of the accused products. The defendant, in defiance of the court order, merely produced photocopies of partial sales data and several invoices, alleging that the original documentary proof were no longer available. The defendant also argued the calculation method adopted by Synthes is flawed: the turnover and operational profit of the accused product is not accurate, the patent contribution rate is not considered, among others.

The court opined that there is no just cause warranting the defendant’s refusal to disclose its account books. As a listed medical device manufacturer, the defendant is obliged to keep an elaborate dossier on the production and sales record of the accused products and should be capable of accurately calculating the sales and profit margin based on its account books.

The court acknowledged that the plaintiff’s evidence might not be accurate, but also concluded that based on the prospectus, annual reports and the narratives published on the defendant’s website, which are available to the public, it would be safe to deduce that the defendant’s illegal profit has exceeded RMB 20 million. The court therefore found the preliminary evidence produced by the plaintiff admissible and awarded damages of RMB 20 million.

Due to the lack of discovery, obtaining evidence will remain a challenge in China. As the nation’s judiciary is growing increasingly pro-right holder, patentees are encouraged to fulfill their burden of proof by leaving no stone unturned in their search for physical and electronic evidence surrounding the business operation and financial performance of the infringer. With the implementation of China’s new Patent Law, we expect to see a trickle-down effect in the alleviation of plaintiff’s burden of proof and the award of significant damages in the long run.

Click here to read all the chapters from Managing IP's China IP Special Focus 2022

Feng (Janet) Zheng

Partner

Wanhuida Intellectual Property

T: +86 10 6892 1000

Feng (Janet) Zheng is a partner at Wanhuida Intellectual Property. She practices in the areas of IP law with a focus on patent litigation. Her expertise also extends to technology-related trade secret and copyright matters.

Feng has served both multinational and Chinese corporations in patent infringement litigations, patent invalidation proceedings and the subsequent administrative litigations, civil and criminal trade secret cases, patent ownership disputes, and disputes over patent licensing agreements. She also advises clients on anti-trust and regulatory matters involving patent aspect.

Feng holds an LLM degree from the University of Chicago Law School and another from China’s University of International Business and Economics. She is admitted to both the China Bar and the Bar of New York State.