Marybeth Peters

Copyright law's twin challenges

Marybeth joined the US Copyright Office in 1973 and has served as Register of Copyrights since 1994. |

Globalisation, coupled with the growing number of increasingly enabled devices (such as the iPad) has presented the biggest challenge for copyright law. Copyright has been part of US law from its inception. Throughout the more than 200 years of copyright law history, it has provided economic incentives to creators and to those who invest in and make creative works available to the public. Copyright law has always had to adapt to new technologies, and each technology presents different circumstances and prompts different legal responses. The fact is that a combination of legislation, court decisions and marketplace solutions has worked well.

However, copyright law has now found itself in the cross-hairs of those who fervently believe the information age is revolutionary and requires a full-scale re-thinking of established doctrines developed before the internet age. Consumers have such convenient, inexpensive access to a wealth of creative works that the public's expectation of what should be available and what it should be able to do with that content is unbelievably high.

Instead of exclusivity given to one distributor for a particular use, to compete in today's marketplace copyright owners must license their works to many competing services and for many competing products. There is an increasing demand to have as much content as possible available on every product and device. Existing business models and licensing practices are no longer doing the job. Congress, the courts and business are struggling to deal with this reality.

The Google Book class action settlement litigation, before the Southern District of New York, clearly reflects this reality. Google engaged in systematic reproduction of millions of books without permission of the copyright owners through scanning operations set up with large research libraries. Once scanned, the books were indexed electronically, and snippets from these could be displayed. The Authors Guild filed a class action law suit against Google alleging copyright infringement. One month later five American publishers filed suit. The Authors Guild and Association of American Publishers resolved the suit with Google through a class action mechanism – a settlement agreement, which allowed Google to continue to scan millions of books into the future.

The effect, if allowed, will be a judicially-created compulsory licence. Only the US Congress has the right to create a compulsory licence; such licences are exceedingly rare and narrowly crafted. Many individuals, companies and organisations, and even a few foreign governments, filed objections to all or part of the proposed and amended settlement agreement, including two Statements of Interest filed by the US Department of Justice on behalf of the United States. The settlement provides that, unless authors opt out of the settlement, theirs works will be included in the agreement and can be used by Google.

Copyright law grants exclusive rights to authors. The term of copyright protection is generally the life of the author plus 70 years. The questions are: 1) shouldn't this be an opt-in instead of an opt-out system; and 2) if approved, will this settlement change the balance chosen by Congress?

Finally, libraries, museums, publishers and many others who wish to use particular works have always struggled with trying to locate copyright owners to obtain authorisation. Many copyright owners, however, despite extensive searching, cannot be located. The internet and the emerging markets for devices providing content have made the problem of these so-called orphan works an urgent issue, both in the US and in other countries. Legislation addressing this problem was nearly enacted in the US; a bill passed the Senate in September, 2008. The Google Book Settlement Litigation, which allows the use of orphan works, has put legislative action on hold. No matter what the outcome of the Google Book Settlement litigation, a legislative solution is needed in the US.

The road ahead for copyright law – in Congress, the courts, the market place and the court of public opinion – is a challenging and difficult one.

Lord Justice Jacob

A courtroom view

In 1990 Robin Jacob QC was a leading barrister, specialising in IP cases. He was appointed a judge in the England & Wales High Court in 1993 and a Lord Justice of Appeal in 2003 and has authored dozens of judgments in IP cases. A longer version of this interview is available at managingip.com. |

What have been the big changes in the past 20 years?

In 1990, in the Patents Court we had just passed the era of Mr Justice Whitford and Mr Justice Falconer – they both served in the war and belonged to a time past. The Court of Appeal had not had any experienced patent judges. Mr Justice Aldous [as he was] had proved to be a good first instance judge and had moved things on.

Since then, things have moved on a lot more. The length of trials has gone down by about two-thirds since the 1970s and by possibly a third since Aldous’s time. The length depends partly on the judge. The other complication is the technology. You hesitate to think how long some of today’s high-tech cases would have taken in the 1970s.

Why is that?

Partly witness statements, partly a change in the culture of judging and of the Bar. There’s still room for improvement there. There’s a time coming when we’ll say: a trial will take so many hours or days and that’s that. The new proposed County Court procedures may lead the way to that. They’re not far from the procedures agreed by a group of judges in Venice a couple of years ago for a proposed European Patent Court.

And costs?

Costs have gone up. To some extent that’s a feature of the trial time going down. Witness statements and so on cuts out actual hearing days but take time to prepare. The other change is skeleton arguments didn’t really exist in 1990 and nor did post-trial submissions.

Other changes?

The other change was the Court of Appeal acquiring a specialist patent judge. It should now have had two and would have done but for the loss of Lord Justice Pumfrey. Patent work has never been busier in our courts.

What do you put that down to?

I don’t know entirely. To some extent it’s a reflection of the worldwide increase in IP litigation. It also a reflection on the influence of the English Court. Someone in industry said to me: we do our small cases in Germany and our big cases in the UK. There are now more big cases.

At one point it used to be said the High Court was anti-patentee because it was knocking out a lot of patents. That was unfair and irrational. There were quite a lot of patents knocked out but why were the cases brought here? The answer was these were weak patents granted by the EPO, you could get a fast trial here, and go directly for revocation. People were doing just that. It was a strong tactic, could lead to settlement worldwide and could possibly be of some significance in the EPO proceedings themselves.

Fast courts attract work and that is another reason for our courts are fast. That can be slightly self-defeating: if too many cases come there will be delays. So far we have kept up, however.

At the same time you had pan-European injunctions in the Netherlands?

Some of that may have been connected. At one point the Dutch judges seemed more ready to find the patent valid at the preliminary injunction stage so people started revocation actions here to forestall Dutch action. Actually now it’s difficult to put a cigarette paper between their judges and ours. We get different results sometimes but that’s different.

Another significant development is there was virtually no contact with other judges in Europe. Now there’s lots. It’s mainly between the Netherlands, Germany and the UK. Beyond that there’s a language barrier but we do our best. I pay attention to judgments in France for example. In general the European judges have got closer. That is a reflection of the times too.

How does it manifest itself?

Formally we meet in the European patent judges symposium organised by the EPO every two years. Every off year is the Venice symposium, which is more confined to the big patent countries than the European patent symposium. On top of that we have informal contacts in various ways for instance. At the beginning of this year there was a goodbye to Jan Brinkhof as a Professor in Utrecht. I, Lennie Hoffman and Simon Thorley were some of the people who spoke at that.

Email’s made a difference too. If you get a case, you can send an email to the Dutch judge saying: have you got this one? Sometimes we agree and sometimes we don’t agree; it’s much closer than it was. They’re the main patent countries and when you’re talking about a European system, unless the Commission or a big coalition of willing countries come up with something better, we’ll stick with what we’ve got. It’s got better on its own anyway.

People have noted in your judgments that you take account of decisions in Europe.

Yes, the contact we have has produced a more cohesive system for Europe.

In trade marks nearly everything has changed. In the UK we had a very stable system, very few cases going to the House of Lords or even Court of Appeal. Now it’s impossible to keep up with the references to the ECJ. European trade mark law is very, very confused. The legislation is not good – there was little consultation about it. The contrast with the European patent is significant. The substantive provisions of the EPC were produced by a brilliant group of experts with no time constraints in the Strasbourg Convention. The trade mark system is peculiar. I once wrote that a hundred years of experience of trade mark law in different member states which had identified some of the basic of trade mark law such as does it have to be trade mark use to infringe?, or how do you deal with comparative advertising? These sorts of straightforward questions were not addressed as they should have been. Everything went into the melting pot. Industry has had to pay and continues to pay for it and the courts are too.

Do you think the issues are being clarified?

No, it’s getting worse. I don’t think the ECJ is a good commercial court. Its work on other subjects, such as VAT, is much better and its constitutional or quasi-constitutional decisions are vital for the very being of the EU. But most members of the ECJ have not been commercial lawyers and I think it shows.

What would be the solution?

It’s very difficult. You’ve got to start from here, with all the cases we have already decided. So even if you now made a specialist panel – which has its difficulties in itself – it would be difficult to get back to a rational picture.

The problem with trade marks is one of the reasons why we don’t want the same system for patents. If one had the ECJ pronouncing on claims of obviousness, claim construction and similar questions and judgments taking two or three years, anything could happen but slowly. That would be very bad for European industry. It’s a bit concerning. Industry is dead against it.

There is the biotech directive saying what is patentable and not patentable. There’s a bit of encroachment into patent law by the ECJ that I think is uncomfortable and could lead to trouble. The enforcement directive could also affect the administration of patents, though not substantive patent law. There is an argument that IP is becoming part of the acquis communitaire, which could become a constitutional problem. If the EU signs the EPC then it becomes part of European law and the ECJ could make rulings. How would that affect non-EU countries who are members of the EPC?

That’s all still to be resolved?

That’s all developments for the future. This current shove may or may not work. Some countries are not keen, such as the Spanish. In France it depends on the department.

If it fails, I think this time it is unlikely that there would be Community opposition to the original EPLA project of a coalition of the willing. You’d have to have a critical mass – the Germans, the Dutch, UK and the Scandinavian countries could have a crack at creating a court for all their cases and hopefully France would join too. You’d treat it as the national court and litigate all the corresponding national patents in that. I’d never seen a constitutional objection to that. In the real world, if you decided a patent dispute for those countries you’ve covered most of the EU. I think it would be cheaper and more efficient.

I’m worried about the current compromises though – the Germans have gone back on bifurcation. They’re worried about losing what they see as the good aspects of their system. I think flexible bifurcation makes sense. The default position should be you don’t do it, but there are cases where you should.

Do all these developments make cases more complicated?

We’re beginning to get scientific advisers more. It was a power created by the 1949 Act but it wasn’t used for many years. The original idea was to get the world’s greatest experts. The tendency now is not to go for the Nobel prize winner, and I think that’s better. Get a good academic – I’ve just been sitting with one, I had a good experience with another and it’s been excellent.

I think it could become commonplace in higher tech cases, though the cost is a problem. In some cases it’s been mooted to use a patent office examiner. I think that could work in appropriate cases. As long as the parties don’t make a fuss the scientific adviser is all right.

Parties are worried that they could influence the judge but none of the scientific advisers have tried to do that. They can explain things: in some cases without help, you can’t even figure out what the dispute’s about never mind who are the good and bad guys. The parties have found it quite good. I hope it doesn’t get interfered with. You get to the point quicker and better and have more confidence that you’re at the point.

The distressing tendency of judges as I accept myself is the length of judgments. We’re all writing too much. Some of it is just putting in unnecessary detail. It is hard to leave out detail. I don’t put in dates that don’t matter, addresses, full names, full case names that don’t matter. Do you always need to know that the company’s a limited company? The White Book could lose 50 pages by dropping “limited” or its equivalent.

Do you look back at old judgments?

Yes. Sometimes you think: that sounded pretty good – did I write that? But other times you think: I wish I hadn’t said that. Sometimes you have to say: I got it wrong. When you get reversed, there’s always two reactions. One is: I got it wrong and I can now see why. Another is: Lord forgive them for they know not what they do. When you’ve made a mistake, you have to admit it’s silly, though sometimes it’s down to the way it’s argued. A case on appeal often looks very difficult to the case below.

Has the standard of advocacy risen?

Yes I think it has. The patent bar is excellent, world-beating. They’re precise, they know their tribunals well. Undoubtedly some of the solicitors seem to do an awful lot of unnecessary work, which is another big difference that has come in over the years. Barristers fees used to be half of the case and now they’re more like 10%. That’s where the costs have gone up. Some of it is complexity, some of it is too many people on the team. On a one one-day application I saw the solicitors used were 15 people – a rugby team! Clients are getting a Rolls-Royce job. The problem is people who can’t afford Rolls-Royces.

We’ll see how the Patents County Court develops under the new rules and the new judge who succeeds His Honour Judge Fysh. The Court has been under an enormous handicap. The Woolf reforms said everyone will have the same rules, so there ceased to be any difference at the County Court. I’ve never agreed with the Woolf same-size-fits-all approach: it's a horses-for-courses rule.

The streamlined procedure was introduced, but by consent only – the side that wanted it would be the winner. It’s not been used too much for that reason.

It’s going to be a hard task for the judge and he/she will have to be tough on the litigants. You have to say: focus on your best point or points. That’s what’s wrong with the EPO procedure – they need some judicial training: how to handle cases that are full-blooded commercial fights. The EPO or someone should produce courses and a handbook on how to litigate before the EPO. I know some advocates would favour that.

The standard of advocacy at the EPO is said to be awful. Far too many points are taken and far too may pieces of prior art cited. English lawyers are trained in court by doing trials before becoming judges: our experience brings to bear in different ways. There are some very good people at the EPO – you’ll see in my recent judgments they have done very well on keeping things stable, even if everything’s not perfect. If they hadn’t done what they’ve done, European patent law would be in a right mess. They’ve done a much better job for patents than the ECJ has for trade marks.

What skills does a good advocate have?

There’s a basic requirement to speak, to deliver. Then there is the ability to focus on on a very few points. Of course there’s the old-fashioned skill of telling what you’re going to tell, tell it, then tell them what you’ve told them. And an ability to debate with the court: to be prepared for difficult questions. A big difference since 1990 is skeleton arguments. We don’t now come into court with blank minds – we have initial views but they are just that. I frequently change my mind in the course of a case: oral arguments really matter, particularly when they’re clashed against each other and you have to choose between them. The strength of the litigator has some influence but cases are basically decided in our system on the evidence. The most important function of all is to get the right evidence in front of the court.

Do you also follow cases in other jurisdictions beyond Europe?

Yes. I think the next generations will have much more to do with what the Chinese courts decide. They have put enormous investment into the IP system.

In the US their system is distorted by the jury trial and the things they do to try and get round it. The whole approach to the law is different. I’ve never met anyone outside the US who thinks it’s rational to try a patent case to a jury. Trade mark cases I can see: they’re consumers, they might be better than judges.

In 2030, where will we be?

I think we’ll have a European patent court by then. One reason is people will be more willing to recognise English as the working language of Europe. What keeps India together with 200 languages? The common language of English. The language of patents is not the language of Goethe and Shakespeare. It’s hardly a language at all. All the scientists are using English.

Machine translations too will be much better. How good they’ll be it’s not for me to say. You can get a general idea but getting the nuance – which is what matters in a patent claim – is hard.

Courtrooms will be more electronic. We’ve had one or two part-electronic trials already. Judges’ IT systems are very slow. We’re pretty backward here. We still have members of the Courts of Appeal who don’t use email, which is a pain. Emails allow you to circulate judgments straightaway.

That’ll be another feature of the European patent court – more video screenings and links. We did it the other day – counsel was stuck in South Africa by volcanic ash and appeared in all day case by video link. It worked and was very effective. He won. I think documents will be more electronic too, I have wondered about that. Judges and litigators will adapt – it will be a gradual development – just as everyone types now, which they didn’t used to.

Will there still be wigs and gowns?

I expect so.

Francis Gurry

The impact of globalisation

In 1990 Francis Gurry was head of WIPO's Industrial Property Law Section. He has since held various offices within the Organization, including special assistant to the director-general, director of the WIPO Arbitration and Mediation Center, legal counsel, assistant director-general and deputy director-general. He was appointed director-general for a six-year term in October 2008. |

I think there have been three big changes at the international level, in no particular order.

First, the emergence of the knowledge economy, which can be measured in thousands of ways. For example, the OECD estimates that 30% of global economic output is due to knowledge-intensive industries and that percentage has grown. That has led to an increasing demand for IP titles and an intensification of investment in knowledge, which in turn has made the stakes involved in IP more important and valuable.

Second is geopolitical change, which has been extraordinary. For example, China enacted its Patent Law only 25 years ago and has been a member of WIPO for just 30 years. Last year, 29% of PCT applications came from Japan, China and Korea, compared to 7.6% in 1994. That has enormous implications and the trend is continuing.

Third, there is the increasing involvement of the market and technology in developing solutions to IP problems. Fifty or 60 years ago, the lead always came from governments or the responsible international organisations by way of laws or treaties. Today, so much of what is happening is a policy response to what has come out of the market or technology. Recent examples of that include DRM and the Google Books project. The market is creating solutions that lawmakers have not yet provided. We should think seriously about this: the market solution may be correct but it shouldn't be the default without discussion.

This third change has come about partly because of the slowness of legislative processes, and particularly multilateral processes. They're slow for bad and good reasons. The bad reason is lack of cooperation and good faith; the good reason is that it is appropriate that countries at different levels of development feel comfortable with changes.

A fourth, more specific, major change has been the TRIPs Agreement. It would be difficult to see something of such a comprehensive nature achieved today.

Looking to the future, I think there will be three trends that follow from the changes I've identified.

First, I think we will see more open innovation. By that, I don't mean just open source but generally an increased tendency to collaborate to find solutions to technical needs. That includes everything such as licensing and technology transfer, open source, R&D contracts and joint ventures.

This is a very interesting development resulting from globalisation and the movement of people, as well as the emergence of information and communication technologies that enable people to communicate with each other. Scientists move about a lot more now and in 2007 22% of scientific articles were co-authored – three times more than in 1985. R&D has been internationalised: according to the OECD, on average 15% of PCT applications cover inventions made outside the country of filing.

It does not mean IP is less relevant; in fact it is more relevant: IP defines rights and obligations of participants in relation to joint projects and the products of them.

Second, geopolitical change will continue. We'll see Brazil and India coming into IP practice more. This will produce a significant change in the landscape and politics of IP and the IP-producing countries: there will be a much bigger producing community. But discussion won't be less complicated – it may be more complicated but different: instead of a north-south divide, it will be more about cultural differences, such as those that sometimes divide North America and Europe. Over the longer term, the countries of south-east Asia and countries such as Chile and Mexico will also become prominent.

Third, there will have to be important infrastructure developments – such as a global search facility for brands, which businesses need to operate globally. There is a role for both the public and private sector there. Part of the deal of IP is that data should be available for everyone to inspect. That is not always the case at the moment and there is work to do on digitisation and connections. The private sector will add services, which businesses might choose to pay for, but we have to improve the public infrastructure to have an effective international IP system.

Clifford Borg-Marks

From firewater banquets to global brands

Clifford Borg-Marks is of counsel with Hogan Lovells in Beijing. He was a diplomat in Beijing in the 1980s before joining Baker & McKenzie's IP practice in China. |

As the 1990s dawned, the Chinese IP space was rather desolate. The IP owner had little to rely on except Civil Code principles and inadequate trade mark and patent laws, and the IP lawyer had few tools to counter infringement.

The People's Courts were run mostly by judges with police or military backgrounds but little legal education and were riddled by political interference, local protectionism and widespread corruption. Judicial action was rarely considered as a means of enforcing IP rights.

The only viable options lay with China's administrative enforcers. But officials had little precedent and legislative guidance. It often felt at the time that we were making it up as we went along, and indeed we were.

Every raid action was a process involving lengthy discussions aimed at "educating" local officials in their own laws, persuading them to commit resources to an action and allowing us to go along to observe. Successful raids were often immediately followed by banquets well lubricated by the local firewater and presentations of red brocade congratulatory banners.

This was unsatisfactory. Dramatic seizures often resulted in pathetic fines and the goods being returned to the infringer – minus the trade marks. Successful appeals were unheard of. Awards of compensation were a rarity, while destruction of goods was uncommon until officials discovered that bonfires made for good TV publicity of their bold efforts to uphold the law.

But then things started moving. A new Copyright Law became effective in 1991. Within days of its entry into effect, there was a sense of excitement as I walked past the new signboard of the National Copyright Administration (NCA) with a representative of Sega Enterprises of Japan to convince its young officials to use their administrative powers for the first time to raid an infringer who was modifying and loading Sega games onto a chip in its games consoles. The discussion was not on when and how, but on whether this was a case of copyright in software or in cinematographic works.

China's continued emphasis on market economics and the release of entrepreneurial spirit that came with it led to unprecedented growth not only in the lawful economy but also in the underground economy. Counterfeiters flourished.

The enforcement machinery struggled to keep up, and the pressure from international and domestic forces piled up. All of a sudden, adequate IP enforcement was talked about as a precondition to China's entrance into the WTO.

It officially joined at the end of 2001, which led to further upgrades of all of its primary IP laws to provide for, among other things, judicial review of administrative decisions, enhanced court powers and border enforcement measures.

The People's Courts, guided by helpful interpretations of the Supreme People's Court, have gained credibility and are now the enforcement channel of choice for IP owners. Infringements are still rife, and registry pirates and cybersquatters still abound, but now we generally have better tools to counter them.

The next 20 years will be brighter. Domestic innovation and exposure to foreign technology will continue to be encouraged and IP awareness among enterprises and consumers will grow. The increasing sophistication of the courts will likely lead to the demise of administrative enforcement within the next 20 years and that is probably not a bad thing.

Some Chinese marks will join the ranks of world famous brands, more Chinese works of cinema and literature will entertain worldwide audiences, and, without doubt, Chinese inventions will change our lives.

Peter Drahos

How TRIPs reshaped IP norms

Peter Drahos is a law professor at the Australian National University, Canberra. He holds a Chair in Intellectual Property at Queen Mary, University of London. He has published many articles and books on the TRIPs Agreement. |

Do you think the TRIPs Agreement can be described as a success for either developed or developing countries?

That depends on how you define success. Did some countries make trade gains out of TRIPs? Obviously yes: the US as an economy got billions of dollars out of it. To a lesser extent other countries also profited – Germany, the UK and possibly Italy with all its trade marks.

On those criteria developing countries suffered heavy losses, particularly South Korea, China and probably India. The poorest developing countries, because they weren't really in the international trading system, didn't really suffer but they had to deal with costs such as having to set up patent offices.

There are other criteria that would make you question whether TRIPs was a success for the US. It did create political legitimacy problems for the WTO that haven't really left the Organisation. Many countries have distanced themselves from it.

China and South Korea don't seem like losers at the moment. In what way did they lose?

When the Agreement was signed they were net technology importers so although China wasn't a member of the WTO at the time the deal was being negotiated, it was the TRIPs standard that the US was asking for. If you compare the patent law the Chinese wanted and the one it got you can see there were differences. For example, China didn't want product patents for pharmaceuticals.

South Korea was and remains a huge technology importer. It is paying out massive royalties and it's not clear what the benefits are. It's also not clear that no-one would have invested in China if it wasn't a party to TRIPs. They were losers in the sense of being technology importers who then had to pay a lot more.

There's a sense among some people in the US that it also lost, because the country opened up its market in exchange for protection of its IP abroad, but that IP is not being protected. Do you agree?

No, not really. Although the US claims that it opened its markets, you only need to look at the agriculture sector to question that. The US has not opened its agricultural markets but that was one of the promises of the Uruguay round, which also produced TRIPs. It's true there was some opening up, but there really has only been modest progress. Agricultural negotiations now are at a standstill.

In some areas enforcement of IP has really improved. For example, patent enforcement in China. It has really developed an enforcement system that companies can use. There has been a lot of progress in trying to make China's Patent Office a world-class office and I think there is general agreement that that has happened. Obviously there are areas of weakness such as copyright enforcement, but overall progress has been made.

What did you make of the US-China WTO dispute on IP and what does that tell us about possible future WTO disputes based on IP?

One of the things the WTO did for developing countries was introduce a dispute resolution mechanism in which developing countries have won some unexpected successes. Ecuador and Brazil have both won cases. It has to be said that the mechanism has done some good for developing countries.

One of the reasons why free trade agreements (FTAs) are being used is that developed countries may be looking to move dispute resolution away from the WTO. I think the US has also underestimated the extent to which countries would use cross retaliation. For example, Brazil recently threatened cross retaliation on IP rights as part of its cotton dispute with the US. It may be that we will see more disputes pushed into FTAs, which all have dispute clauses.

Why have so few companies taken advantage of the Doha Declaration on the TRIPs Agreement and Public Health?

In 2004 and 2005 I did a series of interviews looking into this question and the answer I got was that the system is too complicated – there are too many uncertainties. One member of a Canadian generic association I interviewed said it was likely that one of their members would do it because "it would make their employees feel good". A few years later Apotex did export some drugs to Rwanda but in my opinion this was done symbolically so the WTO could say the system works even when it doesn't.

How do you see TRIPs developing over the next 20 years?

The most important thing about TRIPs from the point of view of developed countries and particularly the EU and US is that it sets a platform – it is a set of standards below which no country can go. But perhaps one of the most important parts of the agreement is the most favoured nation clause, which means that if any country enters into a bilateral agreement the advantages have to be given to other WTO members. This means that the EU and US can use bilateral agreements to push standards higher and higher. It may be that at some point the standards will move to a new level and it may be that these standards get folded back into a renegotiated TRIPs deal but not any time soon. There may be negotiations around issues such as the disclosure obligations related to genetic resources, but I don't see any kind of major renegotiations. The EU and US are happy to use it as a launching pad for bilaterals.

Development never follows the neat paths that social scientists set for it. You don't know what kind of ecological disasters are waiting for us. They might force countries to cooperate more and share technology in ways that are unpredictable. Climate change scenarios really could change the attitude of states to technology transfer. This could make a lot of the IP developments of the 1980s and 1990s quite irrelevant.

Alexander von Mühlendahl

From Brussels to Alicante

Alexander von Mühlendahl was vice-president of OHIM from 1994 to 2005, when he joined the German firm Bardehle Pagenberg Dost Altenburg Geissler. |

The creation of a common European system of IP rights has been on the Brussels agenda from the very beginning, when the Community still consisted of only six member states – a common market requires harmonised national laws and unitary IP rights. The results achieved in the area of trade marks – harmonisation since 1988 and a Community trade mark (CTM) system since 1993 – are great achievements, which have by now been matched in the field of design law and plant varieties, but not in the field of patents.

I was part of the earliest negotiations over the CTM when I worked as an assistant to one of the members of a group of three "wise men" advising the Commission in the 1970s. I later joined the German government (in 1979) and represented Germany in at least 150 meetings at the Council of Ministers where the Harmonisation Directive and the CTM Regulation were negotiated. In 1988, the Directive was adopted, and five years later – having been held up by lack of agreement about languages and the seat of the office – the Regulation. It seemed natural for me to seek a position in OHIM once the Office was set up. From sitting down in September 1994 with nothing but pencils, an empty desk and a couple of telephones it has been a great accomplishment to create a working trade marks (and designs) office, with a location somewhat removed from Europe's business and commercial centres.

At the beginning we had fewer than 20 people – we practically went for lunch together everyday. By 1996 we had around 90 staff, working on the examination guidelines and setting up networks in-house. We were a very young team; the average age was about 30 and that helped create a very friendly, open atmosphere. When we opened for applications to be filed in January 1996 things were initially quite slow, but in March alone we received 20,000 applications. They just poured in.

We were clear from the start that we would accept filings by fax. We were also committed to being a paperless office and creating an electronic database so that people wouldn't have to shuffle files from one examiner to another. That was a defining moment because no other office had done it.

We have come a long way from those early days in 1996 – we are going to reach 1 million CTMs filed soon. OHIM is generating substantial "profits" which require a review of the fee structure and the use of OHIM income. OHIM has established itself as one of the leading IP offices, its practices are well established, thanks also to the Boards of Appeal, and of course also as the result of the case law coming from the General Court and the Court of Justice in Luxembourg. The CJ has so far decided more than 100 cases interpreting the Directive and the Regulation, and a similar number of appeals from the General Court. The latter has to deal with about 200 new cases each year. The CJ's judgments have clarified many issues, notably as regards absolute grounds of refusal and likelihood of confusion. The picture with regard to infringement issues is less clear, and recent decisions have added to the confusion. The General Court's case law has by now become very difficult to follow, and the results seem to vary from very good to questionable. The creation of a specialised IP tribunal is clearly warranted.

Of course there are still challenges for European trade mark law. Back in the 1980s people couldn't imagine that Germany would be reunited and that countries such as Poland and Hungary would be part of the EU. Now, decision making in Brussels is probably more complicated than in the early years of the Community, so changing the law may be difficult. The expansion of the Union also brings new issues with it – such as where does a mark have to have "reputation" to claim protection in the absence of likelihood of confusion (an issue decided properly, it seems, in the ECJ's Pago judgment), and where does a CTM have to be used to escape a non-use challenge, as highlighted by the recent Onel decision of the Benelux office. I think many national trade mark offices believe that use in one member state is not enough. In my opinion any analysis of this question which takes the borders between member states as decisive misses the point of having a single market without internal frontiers. Also, the use issue has been such a strong selling point for the CTM that any requirement of multi-state use would be a huge disappointment. The use question, and many others, and more generally the future of European trade mark law, are under study by the Commission, as mandated by the Council of Ministers in May 2007, and the Munich Max Planck Institute for Intellectual Property has been charged with preparing a study by the end of this year. It will then be up to the Commission to make proposals for amendments to the Directive and the Regulation – I hope European trade mark law will then be in good shape to face the challenges of this century.

Herb Wamsley

Why fee diversion matters

Herb Wamsley has been executive director of the Intellectual Property Owners Association (IPO) since 1983. |

In the patent area, the most important development in the US was the creation of the Federal Circuit in 1982. The Court has largely achieved its objective of bringing uniformity to patent law. Before its creation, there were different doctrines in the regional courts of appeal and there was a great deal of forum shopping.

There is much more uniformity now on the law of infringement and the doctrine of equivalents, for example. Before the Federal Circuit, there were a number of technical issues regarding the US law on patentability and obviousness, for example, which required looking up the precedents of various regional circuits each time.

Complete consistency is a tall order, of course, and we still have an issue with more en banc cases being needed at the Federal Circuit – such as the pending Therasense case on inequitable conduct – but overall I think the Court has been a great success.

In the next 20 years, I think we'll gradually see more international cooperation on issues like worksharing. And patent reform legislation in the US is a goal that we hope will be achieved this year, although that remains to be seen. However, I'm optimistic that we'll have reform before the next 20 years is up.

Patent reform will update the US system on issues such as post-grant review and a first-to-file system, which will pave the way for more international harmonisation.

However, we're very concerned about costs going forward. We're afraid that the USPTO faces the likelihood of much higher levels of fee diversion, which will result in a five- to 10-fold increase in costs for patent applicants in the next decade.

It's a matter for concern because the legislation that is pending gives the Office unfettered authority to set fees without any control over the Congressional diversion of fees. In 2010 alone we're looking at up to $200 million of fees being diverted.

Once the Office has the ability to set fees, the temptation to divert larger amounts will be irresistible. It's like money sitting on the table. It's really a threat to the patent system as we know it in the long run, and it could truly inhibit innovation.

When you look back on the mess that the USPTO is in today with the backlog, it's directly traceable to $750 million of fees being diverted between 1990 and 2004. That's what caused a gradual backlog, because the Office was unable to hire enough examiners to handle its workload during those years.

Although no money has been diverted from 2004 to 2009, if the Office is given fee-setting authority via patent reform, the danger of diversion will be much greater, particularly since the government is now more desperate for money to cover programmes outside of the USPTO.

IP will continue to be very important over the next 20 years, and working toward harmonisation will be critical. However, I do think right now that these problems with the USPTO are the biggest the US IP community will face in the future.

Marshall Phelps

Judicial activism and IP assets

Marshall Phelps joined IBM in 1972, ultimately becoming vice-president for intellectual property and licensing. From 2000 to 2003 he was chair and CEO of Spencer Trask Intellectual Capital. He moved to Microsoft in 2003 as head of IP. Earlier this year he joined the board of directors at patent validity business Article One Partners. |

In the last 20 years, we have seen a much more active approach by the Supreme Court to IP cases in the US. That's going to continue, and it has taken the necessary crunch away from patent reform. The Court has placed some limitations on what owners can do with their rights. As a result, I think the law is becoming a little bit less friendly to ownership issues. Cases including KSR v Teleflex, Medimmune and Microsoft v AT&T have cut against the ownership grain. I suppose after nearly 30 years of having a specific court [the Federal Circuit] dedicated to IP it's understandable how you can get out of balance though, and why the Supreme Court has stepped in.

The Bilski decision is the next big one. The Court most likely took the case because they felt they had to put some limit on business method patents, but the risk is that it will hurt other industries, such as software. The Federal Circuit's machine-or-transformation test has not hurt software patents at all, and I have not been upset by the Supreme Court's other patent decisions so far. However, in the Bilski case, I think you have to be very careful because there is some real risk for the software industry if the decision is wrong.

Overall though, I think there is a much greater recognition of the importance of intangible assets today. That didn't exist when I went to law school and business school. Now, 70% of a corporation's assets are intangible. IP is no longer just a little boutique operation.

This ties in with the trend of increased open innovation between companies. A corporation's IP structure has become so important, because you really have to know what the rules are. Even a company like Microsoft, which spends $8.5 billion on R&D, is dependent on the IP of others. The world is moving so fast right now, and I don't know anything that's going to stop that. I live in an industry where product generations are months rather than years. So the switch in asset ratios of corporations over the last 25 years is a major trend. Those ratios won't go backwards; IP is becoming more and more critical.

Sometime within the next 20 years, I think that the accounting industry is going to realise that as well, and intangible assets are finally going to start showing up on spreadsheets. The financial accounting standards board has to wake up first though. So far, they've ducked the issue, because it's hard to assess the value of intangible assets and they're afraid they'll get it wrong. But not including IP on a company's balance sheet is like telling Napoleon: "I don't know where 70% of your troops are – have a nice battle."

Hisamitsu Arai

Japan becomes an IP nation

Hisamitsu Arai is an IP analyst and president of the Tokyo Small and Medium Business Investment and Consultation Company. A career civil servant, he joined the Japanense government in 1981. He was JPO Commissioner from 1996 to 1998 and was the first secretary-general of the IP Strategy Headquarters in 2003. |

I think the biggest development for IP in Japan of the past 20 years took place in 2002 when the government passed the IP Basic Law and declared its goal of becoming an IP-based nation. This led to the establishment of the IP Strategy Headquarters in 2003 and the IP High Court in 2005. As a result of the IP Basic Law 50 IP-related laws have been created or amended. The IP High Court has also improved IP enforcement and meant that there is more expertise in legal opinion.

I was most closely involved in setting up the IP Strategy Headquarters. This dates back to when I took over as JPO Commissioner in 1996 and changed the policy from anti-patent to pro-patent to create more innovation and creativity. I arranged for a national forum on Japan's IP strategy in 2001 and this recommended many changes to the country's laws and accepted my proposal for an IP Strategy Headquarters. I was appointed the first secretary-general of the Headquarters.

Setting this up was a big challenge because patent and copyright matters were dealt with separately without an overall perspective. For example when I joined the JPO there was a closed patent community that I tried to expand to consider other forms of IP. I felt that we needed to discuss things from a more policy-oriented perspective.

Looking at the progress of these developments, I would say "so far so good". But Japanese companies are still not proactive enough in managing their IP. Japanese companies are accustomed to applying for a lot of patents but are not so good at monetising them or getting involved in patent pools. In addition, they are still sometimes reluctant to litigate. This is changing, but not quickly enough. Japanese companies are facing globalisation and it is time for them to change their domestic IP policies to global IP policies.

Overall, I would say that there are still two major challenges for Japan's IP system: globalisation and the IT revolution. Globalisation means that science and technology now have no national border, which means it is necessary for the Japanese IP system to become more global. The IT revolution means that now every economy is moving from an industrial- to a knowledge-based society.

It is time for us to develop our system further. For example, I think Japan needs to introduce a fair use provision because copyright is changing from the printing age to the information technology age. Our present copyright law is very old fashioned. Everybody is a creator now and the copyright law needs to be updated to reflect this.

At the time that the IP Basic Law was passed Japan's economy was in trouble and the government was looking to make structural changes to utilise the powers of individual Japanese people. This is the reason why the proposal for an IP-based nation was adopted and approved so quickly. There are parallels with the economic crises facing so many governments today. It is time for an overhaul of IP policy to stay up to date with the information society.

Vint Cerf

The internet explosion

In 1990 Vint Cerf was working with Robert Kahn at the Corporation for National Research Initiatives, carrying out speculative research into digital libraries, mobile software and digital objects. In the 1970s Cerf worked with the US Department of Defense on developing computers that could talk to each other. During the 1980s he worked with MCI Digital Information Services developing commercial applications of the net. He joined the Icann Board in 1999, and held three terms as chairman. Since 2005, Cerf has been vice-president and chief internet evangelist at Google. |

You might as well ask me what the internet was like in 1973 as 1990. In 1990 it was clear the net was going to grow. Already we were seeing a doubling of size, starting in 1988, but we didn't have "www".

We had hypertext, mouse clicking and bits of the ARPAnet. In 1989 the first commercial service appeared and "www" but we didn't see users as content producers.

The domain name system was developed pretty much between 1984 and 1986. However, at that point it was still used by academics in the National Science Foundation (NSF) and I think not much else.

By about 1992 the NSF was operating the .com and .org registration process and it was consuming research work. This is when the idea that it should be paid for by the private sector arose.

Network Solutions was given the contract and the domains were about $50 each year for two years for a domain. There was quite a battle over this. Nobody knew how much they cost. This was before "www".

In 1994 "www" was not that visible, commercialisation didn't really catch on. But some speculative registrations happened in 1994 – individuals registering names in .com. At the time top-level domains were more or less restrained to .gov, .edu, .org, .net, .com and .mil.

I would say we saw the dotcom boom start in that part of 1990s. There was a doubling in size in the internet, with accelerated growth until the explosion in 2000. But demand for domains remained even after that.

We started to see some abusive behaviour in 1994, such as typosquatting. With the growing popularity of the internet abuses continued.

There was such an explosive demand for the internet in 1996 that Jon (Postel – another major influence in development of the internet) believed it needed an institution to oversee the domain name space. This led to two years of fairly noisy arguments, but the White House came onside and the Internet Corporation of Assigned Names and Numbers (Icann) became the nexus of the domain name space.

In 1998 Icann became the primary overseer of granting domains.

I have a bias against (new) top-level domains, they make me uncomfortable. If they proliferate it could cause problems, but the way I understand it Icann has put a high premium on them – some say for the money, but I don't think so.

I think it is partly to cover costs; partly to filter top-level domains. I doubt if more than a few hundred will appear a year. Not for technical reasons, but rather procedural.

At the risk of making a prediction, I think the domain name system will not be the only way to find internet protocol identifiers.

We need to explore other binding methods to launch uninterrupted strings. To find a way forward without using heavy oversight, where people who have IP interests in a variety of trade marks can co-exist.

The problem is that trade marks produce unique things, but they are permitted to operate in different spaces. That is OK in the trade mark world, but not in the domain name world.

I predict there will be a non-domain name system in the future, based on interplanetary extension of the internet. These are rich networks that talk to each other and explore the solar system on spacecraft. This is already happening but will happen even more. For example, in 2016 Nasa and the European Space Agency are due to do some space exploration using sensory networks.

Ellen 't Hoen

The rise of grassroots activism

Ellen 't Hoen began working at Health Action International in 1990 and in 1999 joined Médecins sans Frontières (MSF), becoming policy and advocacy director of its campaign for the access to essential medicines. She became a senior adviser, IP and Medicines Patent Pool, at UNITAID in 2009. |

Between the late 1980s and early 90s the public health community was not involved in the development of international intellectual property norms. In the 1990s, the World Health Organization adopted its medicines strategy which was firmly based on promoting the use of generic medicines to reduce cost. However, this took place in isolation of the GATT's Uruguay Round of talks and without consideration for the consequences of the TRIPs Agreement, which came into force in 1995. Some lone voices raised concerns but most health specialists had no knowledge of the substance of the international trade talks. This was a time when obtaining and sharing information were more difficult than today, where, for instance, ACTA information leaks are disseminated quickly and spark global public debate.

The event that focused the world's attention on the new international IP rules was the legal action by a group of drug companies against South Africa in 1998. The companies alleged that South Africa's medicines act violated TRIPs. This case received wide international attention and alerted people working in health to the need to take IP seriously as a factor influencing access to medicines. I sometimes joke that the drug companies actually did the debate on TRIPs and health a big favour.

A coalition of grassroots groups and international organisations got involved. KEI (formerly Consumer Project on Technology) was a great source of information and analysis. Then lawyers and academics said they wanted to help and NGOs very quickly gathered knowledge and shared this with a wider public which helped to demystify IP and mobilise. The internet helped enormously. I remember campaigns in the early 1990s when people sent letters and they might take weeks to arrive. Now organisations with very few resources can share information immediately and take part in international debates and activities.

In a country where so many people are HIV-positive I find it hard to imagine that the South African litigation would happen again. It was so outrageous that it gave everyone a huge wake up call, including pharmaceutical companies. In addition, it occurred just before the WTO meeting in Seattle in 1999. The collapse of those talks was a turning point. I think it forced the Organisation to acknowledge that it needed to look at issues that matter to people, which in a way helped usher in the WTO Doha Declaration on the TRIPs Agreement and Public Health.

In the 1990s the pharmaceutical industry tended to move as one block. That now has changed. We see a greater variety in companies' approaches to respond to the demands for access to their medicines. That is not to say that the problem is solved but I do see greater flexibility to explore new proposals.

After the 2002 AIDS conference, people began to develop proposals for a medicines patent pool to respond to the changed IP environment. Back then the patent holding companies were not open to discuss more open approaches to what they considered their property. When we went back a year ago the response was very different. They realise that they can't deal with AIDS using their old model. To provide the most effective treatment they need to pool their IP. The lack of blockbuster discoveries may also play a part in this new approach. The drug companies know that they need to move into developing markets, which they had previously pretty much ignored. This requires a new attitude towards poor populations. I think companies are more willing to engage with us now. They know that it would be unwise not to for business reasons and for public image reasons.

I think health campaigners' biggest achievement over the past 20 years has been to make health an important political priority. It has led to a change in IP policies and more financing. But funding for health is under threat again. Although we have helped to reduce the prices of certain drugs, if countries are not willing to fund them then the progress made in access to medicines may be quickly lost.

Paul Michel

Balancing politics and the law

Paul Michel was appointed to the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in March 1988. He served as a judge until 2004, when he became chief judge. He retired from the Court last month. |

During the past two decades, the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit has come of age, steering events in America, as well as around the world. The number of IP lawyers and patent agents from other countries who daily access the Court's website for oral arguments and opinions is astounding, especially since our decisions only control in the United States.

At the start of the period the Court worked in relative obscurity, except among patent lawyers. Now the Court's decisions are often reported in the general as well as the legal media. As our work became more widely discussed, the United States Supreme Court began reviewing more of our decisions. Congress also took a keen interest, holding numerous hearings since 2005 as it considered revising the Patent Act. The future of that controversial proposal remains unclear, however.

Meanwhile, IP became more important in other countries as well. Everywhere, legislative and regulatory authorities intervened, starting an on-going public and political policy debate about achieving optimal balances between strong IP protections and other concerns. Upon retirement in June, I intend to join this debate free of restraints that limit what judges may say on such matters.

The next 20 years I predict will see a continuation of this debate, which arises from inherent tensions in all IP regimes, since each regime tries to balance conflicting goals. The most important issue, however, will be whether courts are allowed to modulate legal rules and case results to the full extent of their expertise, or whether popular demands will prompt excessive involvement by politicians who may have only limited understanding of how IP rights are granted and enforced. It is complex. In my view, the welfare of the world will turn largely on how well each set of actors respects the proper role and potential of the others. In my view, each set should exploit its strengths but allow others to compensate for its weaknesses.

On top of all that is the issue of moving toward global harmonisation, as well as dealing with fallout from the TRIPs regime seen by some countries as unfair. I believe the world needs to find ways to meet the concerns of such nations, but in a manner that does not weaken IP protections everywhere and across all technologies. As the scope of inventions eligible for patenting varies greatly from country to country, this divide also needs to be bridged. The outcome of this debate will heavily impact economic prosperity and technological advance in every country.

Twenty years of Managing IP |

|

1990 |

Managing Intellectual Property launched |

1991 |

Magazine sold to Euromoney Publications PLC |

1994 |

IP Contacts Handbook launched |

1996 |

First World IP Survey published |

1999 |

Hong Kong office opened |

Herb Schwartz of Fish & Neave featured on first full-colour cover |

|

2000 |

Managing IP merged with IPAsia |

Managingip.com launched |

|

2003 |

New York office opened |

INTA Daily News launched at INTA Annual Meeting in Amsterdam |

|

2006 |

First Global IP Awards Dinner held at Claridge’s, London |

2008 |

AIPPI Congress News published in Boston |

2009 |

AIPLA Daily Report launched in Washington DC |

2010 |

First China-International IP Forum held in Beijing |

Managing Internet IP introduced |

|

miphandbook.com launched |

|

Number of PCT filings |

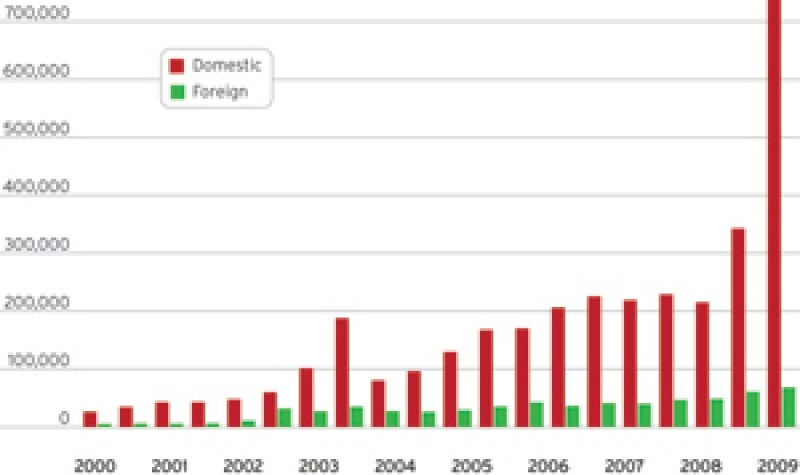

Number of PCT filings by country of origin |

|

|

Source: WIPO |

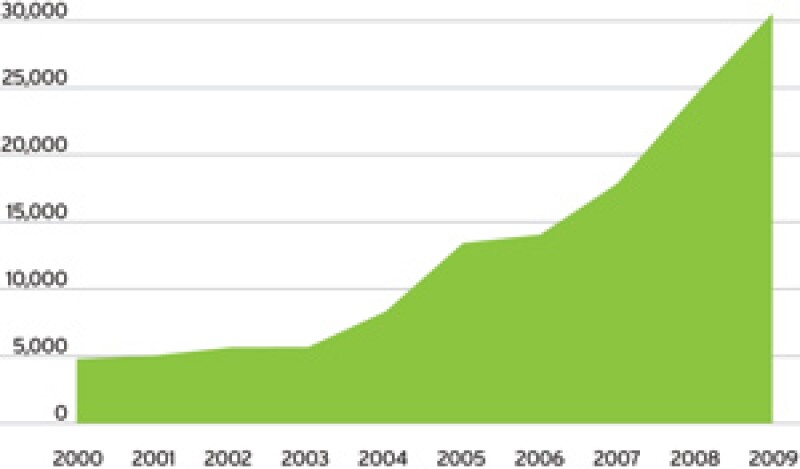

Civil IP actions concluded at first instance in China 2000-2009 |

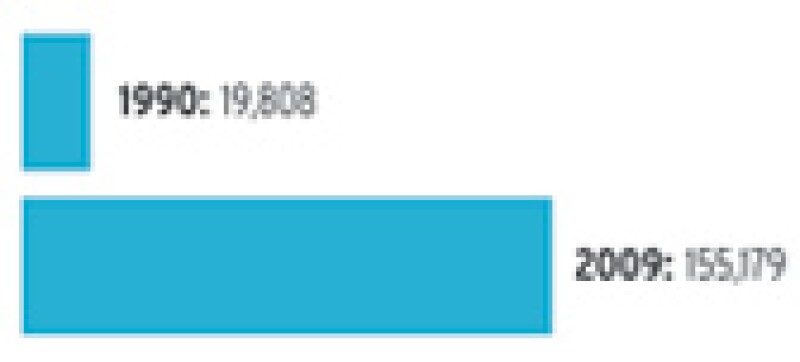

Trade mark registrations in China 1990-2009 |

|

|

Source: Rouse’s China research unit |

EU member states |

Applications for Community trade marks |

|

|

Source: OHIM |

Top 10 PCT applicants in 1990 |

Top PCT applicants in 2008 |

|

|