Choosing the right typeface is often the key to a great logo design, graphic or website. Typefaces, fonts, and their glyphs create IP issues that cover copyright, trade marks, designs, patents and related laws. The copyright status of a typeface varies between jurisdictions.

What can be protected in China? IP owners need to be aware of the current situation and also about how the courts have decided some key cases in recent years

A guide to typefaces and fonts

Technically, a font is a computer file or program (when used digitally) that informs your printer or display how a letter or character is supposed to be shown. A typeface is a set of letters, numbers and other symbols whose forms are related by repeating certain design elements that are consistently applied (sometimes called glyphs) and used to compose text or other combinations of characters.

In China, the situation is more complex. In its 3,000-year history, Chinese calligraphy has seen many evolutional stages, such as oracle bone script, large seal script, small seal script, clerical script, cursive script, regular script, and running script. The seal, clerical, cursive, regular, and running script can be called typefaces. One or several typefaces can commonly be named after a writer because of that writer's artistic achievement or influence. For example, the calligraphy works of well-known calligraphers of the Tang Dynasty like OuyangXun, Yan Zhenqing and Liu Gongquɑn are commonly known as Ouyang style, Yan style, and Liu style, which are defined as typefaces. Typefaces on computers are commonly known as a font family. While litigation involving a font family and fonts has increased, the related protection issues have attracted the extensive attention of the intellectual property community.

Copyright protection

Copyright laws in China protect both typefaces and fonts. Fonts may be protected as long as the font qualifies as computer software or a program (and in fact, many fonts are programs or software). Font families and typefaces, on the other hand, may be copyright protectable as long as they meet the threshold of originality and reproducibility. This is made clear in Rule 3 of the Regulations for the Implementation of the Copyright Law of the People's Republic of China (the Regulations).

In practice, disputes over computer typeface protection focus on two questions: whether a font can be classified as a work of art; and whether a typeface can be classified as a work of art. Rule 4.8 of the Regulations defines a work of art as an artistic work of aesthetic significance, such as painting, calligraphy, and sculpture, which is formed by lines, colours or other elements. Therefore, the above two inquiries point to the originality as well as the independent formation of a work of art.

The courts decide

On the first question, there is a divergence of views in the courts. In Founder v Blizzard Entertainment, the first instance court held the font involved in the

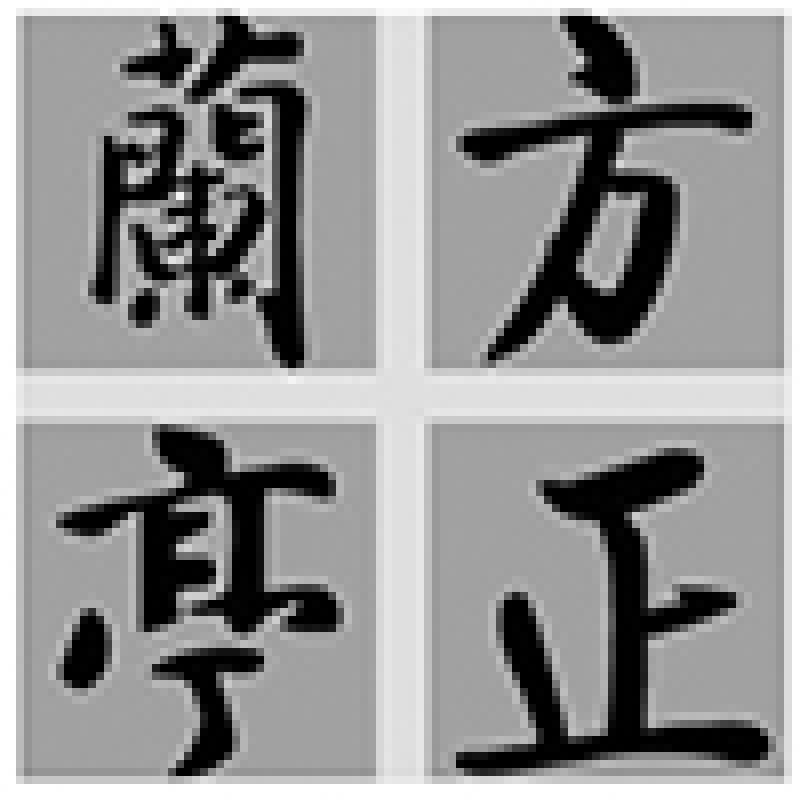

Case – the Founder's Lan Ting Font Family – is calligraphic art of a certain aesthetic significance, which meets the requirements of a work of art specified by the Copyright Law and so can be protected under Copyright Law. However, upon appeal, the second instance court didn't agree with the first instance's viewpoint, but held that the font should be protected as a computer program. The Supreme People's Court then reasoned that each character or letter in the font is automatically generated by computer instruction and related data according to a basic design style and combining rule, rather than separately created by lines, colours or other elements embodying aesthetic significance. In light of this, the Supreme People's Court held that the font can't be classified as a work of art, but as computer software.

In Founder v P&G, the court of first instance held the opinion that Founder put intelligent

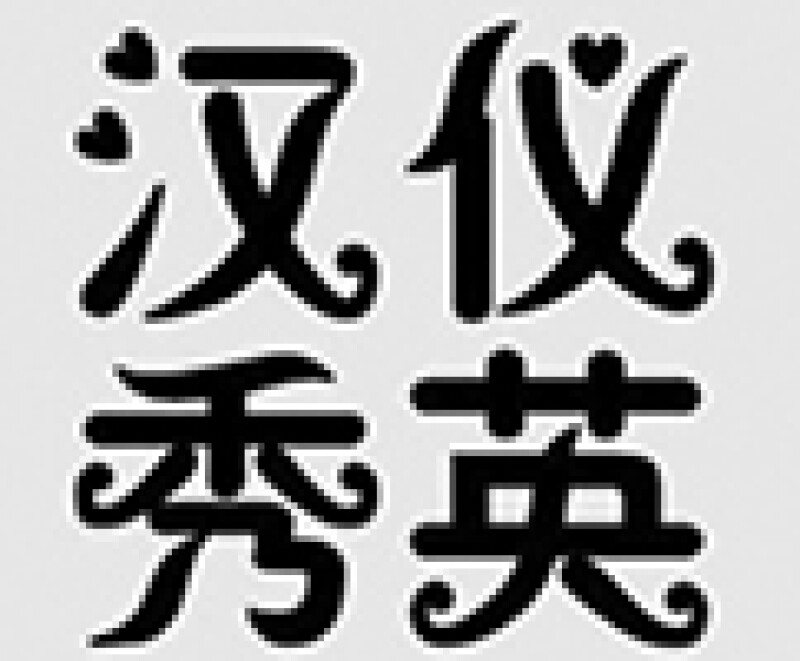

creation into the Qianti Font Family, assembling a collection of characters and letters that have aesthetic significance into a specific font and enabling the font to have a certain degree of originality. This meant that the font should be protected as the work of art under Copyright Law. Similarly, in Hanyi v Xiaobaxi, the Nanjing Intermediate People's Court stated that a font is a collection of individual calligraphic works. Judging from the overall unified artistic style, the font has evident significance and distinctive features and so can be classified as a work of art.

With respect to the second question, it depends on whether the typeface has a featured and creative artistic style, which could be differentiated from those publicly known.

In Founder v Baiweilin, Nanjing Intermediate People's Court stated that ten characters from

Founder's Miaowu Font Family, which was used by Baiweilin, has a distinctive artistic style. With a unique artistic effect and aesthetic significance, each character in the typeface embodies their designers' wisdom and creative labour and could be protected under Copyright Law as a work of art. In Hanyi v Xiaobaxi, Nanjing Intermediate People's Court held that certain characters with originality (not all the characters) in Hanyi's Xiuying font family

could be classified as a work of art. Among the three characters involved in the case, only "Xiao" and "Xi" basically embodied the stroke features in process of creation, while the other one, "Ba", did not show originality. Similarly, in Hanyi v Frog Prince, Jiangsu's courts at two levels stated that only those typefaces that embody highly unique aesthetic appreciation as well as being clearly differentiated from existing ones are likely to be protected under Copyright Law.

Computer software and programs

We believe that a font should not be classified as the work of art, but can be protected as computer software or a program. A font is a collection of bitmapped fonts or a vectorisation of data with a unified style of design. It is generated by means of technology including scanning, spelling, digitalised matching and symbol collocation. The font is merely a practical tool operated by software or a program, rather than a piece of work embodying aesthetic significance. Accordingly, we agree with the views that a font should not be classified as a work of art.

|

|

"For a typeface, the focus lies in whether a typeface possesses originality, as well as whether a typeface can independently form a work of art" |

|

|

Nevertheless, some people hold that a font should be classed as a compilation work. Article 14 of the Copyright Law of the People's Republic of China states that: "if works compile several works, fragments of works, or data or other materials that do not constitute works, and embody originality in the selection or organisation of their content, such works can be called the work of compilation." While a compilation work requires selection and organisation of its contents, a font is just a computer file or program that informs your printer or display how a letter or character is supposed to be shown. Besides, with respect to a font for Chinese characters, the characters' number and order are both regulated by national specifications, but not decided by the designers. In this regard, because of a lack of originality, a font should not be classified as a compilation work.

In practice, the protection of fonts mostly relies on the protection given to computer software or a program as defined in Rule 3(1) of the Regulations for the Protection of Computer Software. In Founder v WeifangWenxing (first instance), the court held the opinion that: "the font formed by coordinate data and command of all characters can be executed by the computer, which could be classified as computer software as defined by the Regulations for the Protection of Computer Software in China and should be protected by such regulations."

In the case of Founder v Blizzard Entertainment, the Supreme People's Court held a similar opinion. As mentioned above, a font can neither be regarded as the work of art, nor the work of compilation, but only a kind of database and its operation must be based on the related software. In light of this, we agree on the point that the related software should be the object of protection for a font by the Copyright Law.

The importance of originality

We believe a typeface is protectable if it possesses originality and can independently form a work of art. For a typeface, the focus lies in whether a typeface possesses originality, as well as whether a typeface can independently form a work of art. The artistic creation rule and the theory of Copyright Law need to be taken into consideration. According to the judicial interpretation, originality should comprise "independent completion" and "creative feature". Article 15 of the Interpretations for Several Issues of Applicable Laws for Hearing Cases of Copyright Civil Disputes by the Supreme People's Court states that: "If a work is developed for one theme by different designers, such a work is completed independently with creative features. Each designer should be deemed to have their own independent copyright." The term "independent completion" requires that designers develop their works in an independent way without plagiarising other designers' work; "creative feature" requires that a typeface, as compared with one that is publicly known, can easily be identified because of its unique styles. A specific typeface that can easily be identified can meet the requirement for originality.

Copyright plays a key role in the protection of typefaces and fonts. For typefaces, as long as they meet the threshold of originality and reproducibility as a work of art defined in the Copyright Law, they may be protected. We believe that the courts should not adopt a relatively high standard on the affirmation of originality and aesthetic significance. If the specific character or letter in the typeface possesses a unique style which could be differentiated from the publicly known one, it can be classified as a work of art and be protected. Since fonts cannot be classified as a work of art, or a compilation work, the protection may fall into that of the related software. This makes it very important to identify the legal attribute of typefaces and fonts, which would help enterprises to specify their claims in possible disputes over rights and avoid the problems and expense caused by inappropriate requests.

Wu Di (Deland) |

||

|

|

Wu Di (Deland) is a partner and senior trade mark attorney at Lung Tin and the head of the Trade Mark & Copyright Department. She focuses on all trade mark matters ranging from trade mark registrations, oppositions and reviews to licensing and transactions, particularly in procedures after rights have been granted, such as trade mark oppositions, reviews, and litigation as well as other complex trade mark matters. She has worked extensively with Japanese clients and is fluent in Japanese. Wu started her career as a trade mark attorney in 2005. Before joining Lung Tin in 2011, she worked in Japan with Kyoritsu International as a trade mark attorney handling all kinds of trade mark matters and maintaining relationships with Chinese clients. Wu obtained her master’s degree in Economic Science from Nanzan University (Japan). |

Wang Lvyun |

||

|

|

Wang Lvyun is a trade mark attorney at Lung Tin. She has extensive experience in trade mark matters. She has handled thousands of trade mark registration cases, reviews, oppositions and disputes in China for foreign clients. She provides analysis and consultancy related to trade mark matters, as well as global trade mark solutions for domestic enterprises. Before joining Lung Tin, Wang had worked for China Trademark & Patent Law Office from 2007, primarily being responsible for trade mark registration, renewal, licensing, assignment, opposition, reexamination, disputes and well-known trade mark recognition in China for foreign clients. She also did global trade mark registration and protection work for domestic clients looking to expand, which included use of the Madrid System and the Community Trade Mark. Wang obtained her Master of Laws from China Renmin University. |