In Korea, patent term extension (PTE) of a maximum of five years may be granted once for a patent covering a drug or agrochemical that has to obtain marketing approval after patent registration. According to Article 95 of the Korean Patent Act, however, the scope of protection during the extended period is limited only to the working of the patented invention in relation to products whose marketing approval was the basis for PTE.

Original approved product

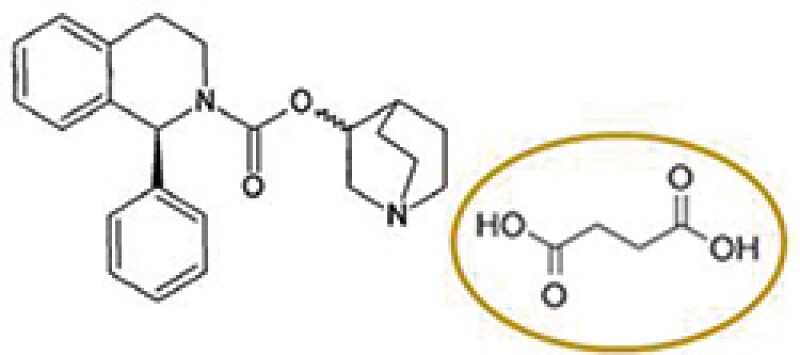

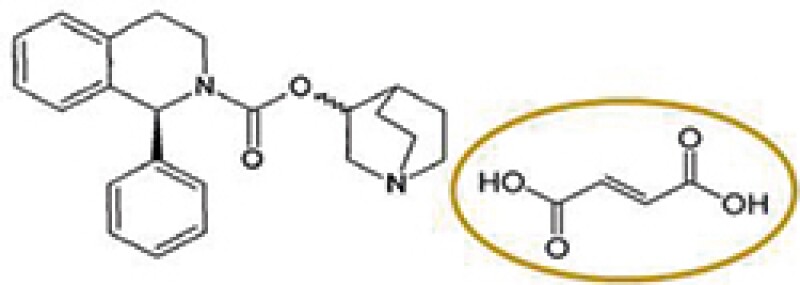

Solifenacin succinate

Accused product

Solifenacin fumarate (a different salt)

The Supreme Court recently acknowledged that the scope of a patent whose term has been extended covers a different salt form from the original product (Supreme Court Case No. 2017Da245798 decided on January 17 2019). This is the first case where the Supreme Court has extended the patent scope during the PTE period to cover a different form of an original drug.

Astellas Pharma (Astellas) has a patent covering solifenacin succinate, which was granted a patent term extension based on the approval of Vesicare® product containing solifenacin succinate as an active ingredient. A local pharmaceutical company acquired marketing approval for a product comprising solifenacin fumarate and began to sell the product after the expiry of the original term of Astellas's patent and during the PTE period. Thus, Astellas filed a patent infringement action against the local pharmaceutical company claiming that the sale of solifenacin fumarate infringes the patent for the original approved drug under the PTE.

The key issue in this case was whether the fumarate salt of solifenacin falls within the scope of Astellas's patent under the PTE that was granted based on the succinate salt.

The Patent Court interpreted that (i) the scope of PTE protection is limited to the scope within marketing approval, which was the basis for PTE; and (ii) the accused product with a slight difference is deemed to be substantially identical to the original product if the accused product does not require new approval for marketing independently from the original product. Based on this, the Patent Court decided that since solifenacin fumarate, a modified salt, requires new marketing approval separate from solifenacin succinate, the scope of PTE protection provided for the succinate salt of solifenacin does not cover the fumarate salt (Patent Court Case No. 2016Na1929 decided on June 30 2017).

Furthermore, the Patent Court rejected Astellas's argument that solifenacin fumarate is equivalent to solifenacin succinate on the grounds that the purport of Article 95 is to restrict the scope of PTE protection, and thus the doctrine of equivalents should not be applied to interpretation of the scope of PTE protection under Article 95.

However, the Supreme Court overturned the Patent Court's decision. The Supreme Court applied different principles to determine the scope of PTE protection based on whether the accused product is identical to the original approved drug in terms of the active ingredients, treatment effects, and uses. Ultimately, the Supreme Court indicated that even though the accused product is different from the original approved product in terms of a pharmaceutically acceptable salt etc. it should be viewed that the scope of protection for the original approved drug during the extended period covers the accused product if (a) such difference is easily adopted by a person skilled in the art and (b) the treatment effects and uses shown by the pharmacological action of the active ingredients are substantially identical in the two products.

In this case, regarding issue (a) mentioned above, the patent specification describes succinic acid, fumaric acid etc. as selectable organic acids capable of forming salts with solifenacin, the active ingredient. It is widely known in the art that solifenacin fumarate has the same administration route and absorption process as solifenacin succinate. In view of these findings, the Supreme Court held that a person of ordinary skill in the art could have easily selected solifenacin fumarate instead of solifenacin succinate.

For issue (b), the Supreme Court ruled that the two drugs would have substantially identical treatment effects because the accused product acquired marketing approval by submission of bioequivalence test data showing that the accused product has an equivalent effect to the original approved drug.

As such, the fumarate salt could easily be selected by a person skilled in the art and the treatment effects would be substantially identical in the original product and the accused product. Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that the fumarate salt of solifenacin falls within the scope of PTE protection for the patent.

Before this case, generic companies had rather freely marketed their drugs in different salt forms right after the expiry of the original patent term, even if the patent right could still be protected under PTE. This new case will have, at the least, a chilling effect to deter entry of generic drugs with different salt forms. According to the Supreme Court's logic, generic drugs with a mere change of salt forms may constitute infringement of the patent for an original drug, while some groups would not be liable for patent infringement, e.g. when different salt forms would not be easily selected by those skilled in the art, or exhibit remarkable effects unexpected from the original drug.

For original drug companies, it would be advisable to list as many possible salts of the active ingredient in the specification so as to minimise any possible modification by a third party. Further, careful prosecution of a product patent application is recommended so as to avoid any file wrapper estoppels that affect claim construction.

Generic companies now need to review the patent portfolios of original drugs in more depth, and if a new salt form has been developed, they may need to focus on its remarkable effects over the patent. Filing a patent application for salt forms would be another choice to receive preliminary judgment on constitutional difficulty and remarkable effects by KIPO.

Min Son

Partner, Hanol IP & Law

HANOL Intellectual Property & Law

6th Floor, Daemyung Tower, 135, Beobwon-ro, Songpa-gu

Seoul, 05836

Republic of Korea

Tel: +82 2 942 1100

Fax: +82 2 942 2600