The International Trademark Association (INTA) defines a trademark coexistence agreement as "an agreement by two or more persons that similar marks can coexist without any likelihood of confusion" and "allows the parties to set rules by which the marks can peacefully coexist". In practice in China, a trademark coexistence agreement often appears in the form of an agreement signed by two (or more) parties, or a letter of consent issued by the owner of an earlier trademark registration to the applicant of a later filed application. Although academic circles still argue about the validity of trademark coexistence agreements, the number of cases where trademark applicants use trademark coexistence agreements to obtain trademark registration in administrative cases involving the granting and confirmation of trademark rights has gradually increased. Applicants should be aware of this and apply it appropriately.

We have collated some information for applicants' reference regarding several major issues in the application of trademark coexistence agreements.

Validity of trademark coexistence agreements

China's Trademark Law and the Regulations on the Implementation of Trademark Law have no specific regulations on trademark coexistence agreements. Article 8 of the Trademark Review and Adjudication Rules stipulates: "During the course of a trademark review and adjudication, the parties concerned are entitled to dispose of their trademark rights and their rights relating to the trademark review and adjudication pursuant to the law. On the premise that the social public interest and the right of any third party are not affected, the parties may reach reconciliation in written form based on their own discretion or mediation." This provides a basis for the application of trademark coexistence agreements.

The Trademark Review and Adjudication Board (hereinafter referred to as the TRAB) has recognised the validity of coexistence agreements in principle since 2007, and has taken such agreements into consideration when examining the similarity of marks in review and adjudication cases. The courts have adopted more tolerant attitudes than TRAB towards trademark coexistence agreements. In 2016, more than 80 trademarks were approved for registration by courts of first or second instance based on the acceptance of trademark coexistence agreements. In 2017, more than 90 trademarks were approved by the courts based on trademark coexistence agreements.

Although the TRAB and courts have generally recognised the validity of trademark coexistence agreements, it is also believed that coexistence agreements cannot completely replace the examination on the likelihood of confusion and cannot be a sufficient reason for the registration of a trademark. If the coexistence of two trademarks can easily lead to confusion in the relevant public or is detrimental to public interest, even if there is a coexistence agreement, the later filed trademark cannot be approved for registration.

Conditions for trademark coexistence agreements

Trademark coexistence agreements are mostly used in administrative trademark cases involving the granting and confirmation of trademark rights before the TRAB and people's courts. When trying such cases, the TRAB and the courts will consider all factors to reach a decision, including the trademark coexistence agreement, the degree of similarity between the trademarks, the relatedness of the designated goods/services, and the popularity of the trademarks.

1) The degree of similarity between the trademarks and relatedness of the designated goods

If the designated goods of both parties are in the same subclass of Classification of Similar Goods and Services but the degree of relatedness between these goods is low, and the trademarks of the two parties are similar to a certain extent but can still be distinguished by consumers as a whole, then the coexistence can be allowed. On the contrary, if the designated goods of both parties are identical or very similar and the trademarks of the two parties are the same or very similar too, the coexistence is likely to be rejected as consumers will struggle to distinguish the two marks.

2) The popularity of trademarks

If the earlier registered mark is well-known and the use and registration of the later filed mark can easily cause confusion, the coexistence of marks is not allowed. If the later filed mark has actually been used and has a certain amount of popularity through use and the consumer can distinguish it from the earlier registered mark based on its popularity, the coexistence can be allowed. If the two marks are both well-known or both not well-known, the standard will focus on the similarity of marks and relatedness of the goods, as described above.

3) No harm to public interest or any third party

If the later filed trademark covers public resources that should not be monopolised, such as chemical molecular structures or names of raw materials of the product, the coexistence agreement will not be accepted. If the designated goods of the mark relate to public health, for example goods in class 5 or class 10, trademark coexistence agreements should be strictly examined to prevent detriment to public interest or third parties.

4) Acceptance of partial coexistence agreements

If some of the designated goods of the later filed trademark are identical or very similar to those of the earlier registration, but the other part is not that similar, the coexistence agreement could be accepted only for the latter part.

The general standard for acceptance of coexistence agreements is the higher the degree of similarity between trademarks and designated goods, the lower the chances of acceptance of the coexistence agreement. In contrast, the lower the degree of similarity between trademarks and designated goods, the higher the chance of acceptance of the coexistence agreement. However, different cases may vary according to specific circumstances.

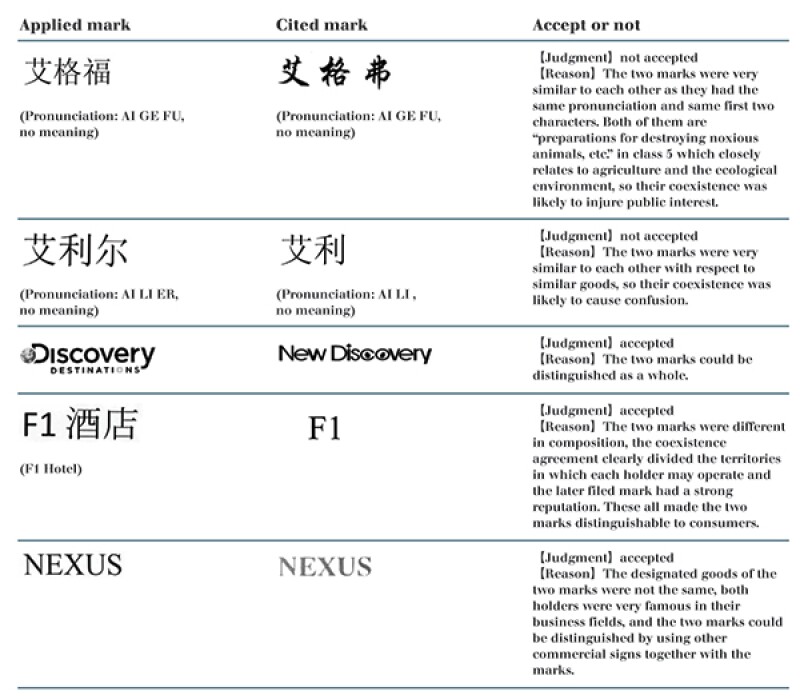

Some judgments on coexistence agreements

We have listed some judgments made by the Chinese people's courts involving co-existence agreements for reference.

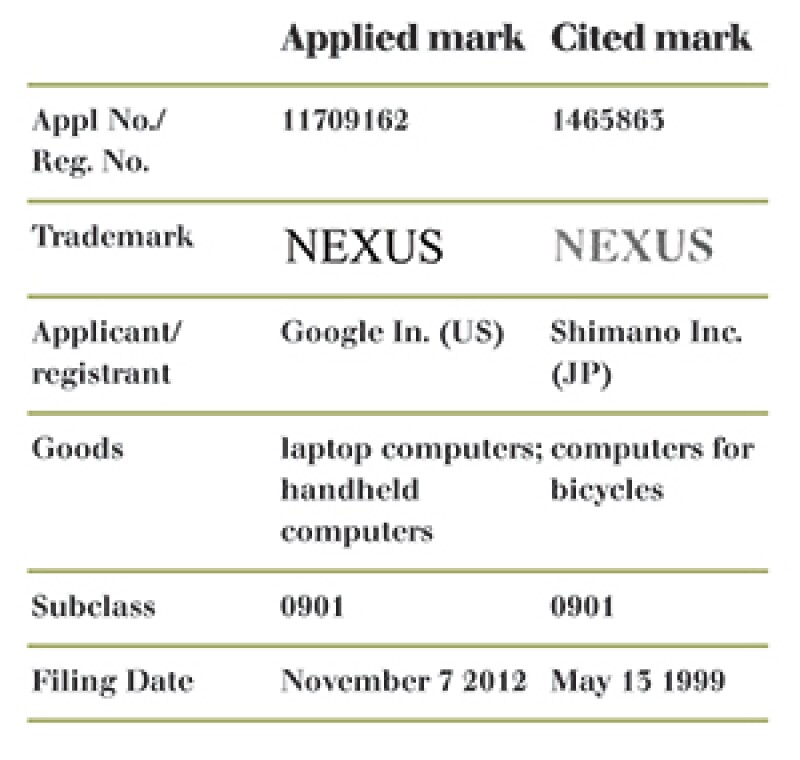

The last case is one of the intellectual property cases selected by the Supreme People's Court in 2016, which has great guiding influence on the trial of trademark coexistence agreements. The detailed information is:

The marks of Google and Shimano are identical to each other, the goods of which are both in subclass 0901 and closely related to each other according to the Classification of Similar Goods and Services in China. The trademark office and the TRAB refused Google's mark, citing Shimano's mark. In the lawsuit procedure, Google submitted a letter of consent issued by Shimano, but the court of first and second instance both refused the letter as they held that the coexistence of the two marks would create confusion and harm the consumer's interest due to the strong similarity of the marks and relatedness of the goods. The Supreme People's Court overturned this decision giving the following reasons:

Firstly, the designated goods of Shimano were closely related to bicycle sports, while the goods of Google belonged to the field of consumer electronics. Although they both included computers, they had differences in functions, purpose, sales channels and usage methods.

Secondly, the letter of consent issued by the cited mark owner is one of the ways to dispose of his legal rights and should be respected. Compared with the uncertain harm to the public interest, the registration and use of the applied mark has more direct and realistic effects on the benefits of Shimano. The letter of consent indicated that Shimano adopted a negative or tolerant attitude towards the possible confusion and misrecognition among the relevant public caused by the applied mark. In particular, Google and Shimano are well-known enterprises in related fields. There is no evidence that Google traded off the fame of Shimano and the cited mark in bad faith when applying for or using the applied mark. There is also no evidence that the registration of the applied mark will harm the national interest or the public interest. In the absence of objective evidence, it is not appropriate to simply use the uncertain "harm to the interests of consumers" to reject the letter of consent.

Thirdly, the trademark is mostly used to distinguish the origin of goods or services, but corporate name and font size, packaging and decoration of products and other commercial signs can also help to distinguish the origin. Even if the applied mark is granted, it can effectively avoid confusion and misrecognition among consumers when used in conjunction with other commercial signs in actual use.

Comprehensively considering the differences between the two marks, the relatedness of the designated goods, and the letter of consent issued by Shimano, the Supreme People's Court judged that the application for Google's trademark should be registered.

Before this case, both the TRAB and the courts did not accept coexistence agreements for marks with a high degree of similarity and covering closely related goods. After this case, although the TRAB still takes a comparatively conservative attitude to such marks, the acceptance of the courts has increased since 2017, which is positive news for applicants who want to use coexistence agreements in litigation.

Requirements for trademark coexistence agreements

1. Basic contents of the coexistence agreement

The coexistence agreement must be signed by the owner of the earlier filed mark and the applicant for the later filed mark. The letter of consent must be issued by the owner of the earlier filed mark. A basic agreement or letter of consent must include clear identification of the parties, the marks and the list of goods/services for which the marks will be used. If the agreement or letter of consent contains information on geographical areas where each party is permitted and not permitted to operate, necessary measures to avoid confusion, etc. it will have stronger effect and be accepted more easily.

2. Translation, notarisation and legalisation

Agreements in foreign languages must be translated into Chinese. If the document is formed abroad, it must be notarised and legalised. If there is no translation or no notarisation or legalisation, the validity of the agreement will not be recognised.

3. Time limit for filing coexistence agreements

In cases of trademark review of rejection before the TRAB, the document must be filed within three months from the filing date of review. A grace period of a few more months is possible, if it is allowed by the examiner through communication. If it is not possible to submit it to the TRAB, the applicant may submit it to the court in the subsequent administrative litigation procedure.

With the development of the economy and society and the increasing rate of filings of trademark applications in China, the number of similar trademarks is increasing. The acceptance of coexistence agreements respects the parties' disposition of trademark rights and is also a practical solution for the large number of similar trademarks in China. Applicants can proactively use this tool to obtain trademark registration and avoid potential trademark infringements. On the other hand, the coexistence of similar marks in the market may weaken the distinctiveness and influence of the mark and may require a lot of expense. The applicants in each case should judge the appropriate action in light of their particular situation.

Jiayan Xie |

||

|

|

Jiayan Xie is a trademark attorney at DEQI Intellectual Property Law Corporation. She obtained her LLB degree in international relations from Renmin University of China and received IP training in the United States in 2006. Jiayan has practised intellectual property law for over 15 years. She has extensive experience in trademark clearance searches, registrations, oppositions and appeals, and represents international and multinational corporations in prosecution, cancellation and litigation proceedings. |