Manufacturers of fast-moving consumables spend tens and even hundreds of thousands of dollars getting the packaging and presentation of their products just right. In order to appeal to fussy consumers faced with a daunting array of options, it is not enough to simply have a great product or even a stylish product. The presentation and packaging has to push just the right buttons, initiate a purchase and sustain product loyalty.

Manufacturers of products as diverse as shampoo and dog food, pencils and yoghurt employ marketing and design teams to create the perfect packaging and presentation for their goods. From the shape of the container to the font used on the back of pack, every element that the consumer will see at the point of purchase is expertly managed and expensively contrived. Companies use focus groups and surveys to decide which puppy photo and which colour have the most appeal, and to determine which combination of visual elements is likely to work best.

This combination of visual elements is of course referred to as the trade dress or get-up of the product – the visual totality of the words, pictures, colours and shapes that determine how the product appears to the consumer. And it is this get-up, created at such expense and so important to a product's success, that manufacturers are keen to protect like never before.

SEE ALSO: FROM BREXIT TO SOCIAL MEDIA: SIX KEY ISSUES AFFECTING IP AND FASHION

The reason for the greater interest in the protection of get-up recently is not simply that it is now recognised as a valuable investment; it is because important elements in the get-up of successful, established market-leading products are being exploited and adapted by competitors.

Increased competition and reduced margins in all retail areas have led to a proliferation of home brands and own brands in all market sectors from groceries to hardware and even in the traditional and previously safe outlets for premium goods such as department stores, hardware stores and quality supermarkets. On top of this is the growth of chain discount outlets such as Aldi and Home Depot, which challenge the traditional outlets, their products and their markets.

These home-brand and own-brand products don't just emulate the best-selling product in a particular sector and offer it under another primary trade mark, they often adopt many of the get-up elements of the product, sailing very close to the original product's get-up. And it is this that this driving the manufacturers of the original products to despair – given the time and effort they have invested in creating the get-up and then building its reputation – and causing them to look for new and creative ways to protect that get-up.

Fallen in the gaps

The reason get-up protection is proving so hard is that it tends to fall between the gaps of traditional intellectual property rights.

The intellectual property elements that are comprised in the get-up of a product include standard trade marks (words, logos, slogans, colour, shape), copyright (artistic and literary works) and designs (in the goods themselves if displayed and the container or packaging).

The get-up might also have been used for so long that it has acquired a reputation that can be protected by various common law and legislative rights. The trick here however has been for the manufacturer of the copy-cat product to distinguish between what get-up elements are common in the trade (and therefore can be used by anyone) and what are distinctive of a particular product (and therefore cannot be used by others).

Taking into consideration copyright in any artistic or literary work that appears on pack and reputation-based rights acquired through use, clever competitors will simply adapt the get-up elements that are not registered or protected into their own packaging, often creating an obvious copy-cat product that the manufacturer of the original product can do nothing about.

The other difficulty is that the creator of a copy-cat product might choose some key get-up elements in a product but mix them with their own distinctive elements, or vary them to some extent. A consumer will not then necessarily be confused, but the manufacturer whose get-up has clearly been the inspiration for the copy-cat product feels that the value of that get-up and the investment in it has been diminished.

So how can trade marks be used to help in the protection of get-up? Manufacturers are registering all sorts of combinations of pack and product representations (including colour and shape marks) in an attempt to do this. But the real question is how this is likely to work out when the marks are enforced?

Maltesers test case

|

|

This question was tested when Mars sought to enforce its registered trade mark for the Maltesers packet against a copy-cat product in the Australian Federal Court (Mars Australia Pty Ltd v Sweet Rewards Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 606 and Mars Australia Pty Ltd v Sweet Rewards Pty Ltd [2009] FCAFC 174). Mars held a registration for the front of its famous Maltesers packet (top right). The actual product was sold in identical packaging (bottom right).

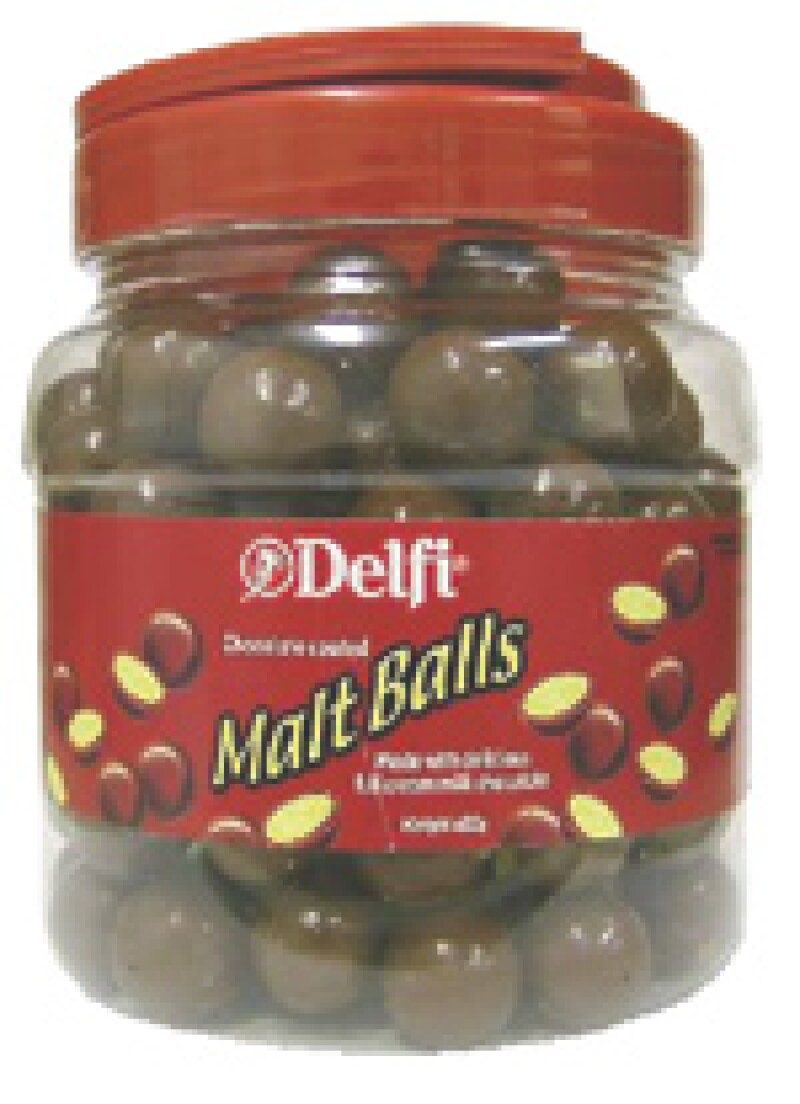

Several discount department stores started selling a look-alike product named Malt Balls in packaging (as shown).

Mars sued the manufacturer for, amongst other things, trade mark infringement. The Federal Court of Australia, and on appeal the Full Federal Court, found that no trade mark infringement had occurred. The analysis the courts applied went roughly as follows:

The word Maltesers is the distinguishing feature of the Maltesers registered trade mark.

The word Delfi on the Malt Balls product is clearly used as a trade mark.

The use of the words Malt Balls, diagonal writing, a red background and product shots on pack are common to the trade and, particularly given the dominance of the word Delfi, are not being used as trade mark elements on this product.

The mark Delfi is therefore the only trade mark on the product. This mark is in no way similar to the Maltesers registered mark (of which the word Maltesers is the essential element) and so there is no trade mark infringement.

Needless to say, the courts also found against Mars on reputation-based rights. In fact, this was a case where being too famous was a distinct disadvantage since the courts found that no consumers would confuse a product that carried similar visual elements as the Maltesers product in the absence of the well known Maltesers word mark. Mars was "a victim of its own success".

The question is how might this outcome have been different and what lessons can we learn in the protection of product get-up? For example, a review of the Australian Trade Marks database does not reveal any application for the background for the Maltesers packaging on its own, without the word Maltesers. You have to wonder if, with all the use, such a mark might not have been registrable, or at least worth a try.

Of course, such an application might have failed on the basis that the background elements were decorative or descriptive and that use of the Maltesers label could not be extrapolated to imply distinctiveness of the background elements as a separate, stand alone mark. But perhaps we'll never know.

There are certainly distinct advantages in having a go:

It is going to be a cheaper and less damaging lesson to learn that your background mark is not distinctive in a trade mark application setting. Failure, or at least a struggle, in the application process will prepare you to deal with the onerous evidentiary burden if and when you seek to enforce your rights in court.

During the examination stage of an application (as against any opposition) there is no third party with a vested interest raising objections to acceptance of the mark and no great urgency. This allows you to argue the distinctiveness of the mark without distractions.

While a trade mark registration will often be attacked once enforced in court as a standard defensive strategy, many matters do not get to that stage. A registration is a strong, clear right and can be used as the basis of a cease and desist demand.

Lessons learned

Based on the lessons learnt from the Maltesers experience, here is a check list of dos and don'ts to use when assessing what get-up marks to consider registering:

DO

Work out what is valuable and important. – The key to good get-up protection is assessing what in the get-up is really key to the success of the product and what element or elements are likely to be adapted by others. Only protect these.

Work out early what is valuable and important. – If you wait too long to try and protect important elements of your new get-up it might be too late. Questioning which get-up elements are trade marks allows you to apply for them before they become common or generic and also helps to focus marketing efforts on emphasising these elements as trade marks in the same way as words or logos. This can also assist where evidence of use might be required for registration. Use your get-up as a trade mark if you want it to be treated as such.

Build layers of protection with multiple marks. – Use a suite of marks covering different essential or key elements in each mark (such as background pattern, product shape, dominant colour).

Question the value of every mark. – Do a cost-benefit assessment of each mark as against your get-up. You can't register everything so work out priorities based on what will hurt most if it is adapted by someone else. Don't just file words, logos and stylised words because they get registered most easily.

Take a risk. – You might not be able to register your single colour mark but you might be better off having a go and failing. If you are able to register the hard-to-get marks, there is a commensurate benefit in protection.

Own the get-up. – Jump on problem use and own the get-up or be prepared to give it away. Treat it like a mark. You might not always succeed but other manufacturers might think twice before using aspects of your get-up.

DON'T

Try and cover everything in one mark. – This is really the converse of much the above. It is important not to distract from the key elements that you want to protect so leave out anything extraneous. Otherwise the court may reach a view about what is essential in your mark and disregard the rest, or might only find there has been an infringement if all the elements collectively are used by a third party.

Include a distinctive word mark to make non-distinctive get-up material registrable. – Such a mark is just not worth the effort and won't give any protection to the get-up material it also contains. And often it will just create a false sense of security, leading to angry queries from businesses as to why a competing product can't be stopped.

Examples of get-ups

The Australian Register is replete with examples of get-up marks but apart from the Maltesers case, the courts have to date had little opportunity to consider these. Here are just a few examples.

There is a large range of get-up related marks for the Ferrero Rocher individually gold-wrapped and boxed chocolate products including the following three dimensional marks and a label mark:

|

|

|

And similarly with the Baci products, (which are wrapped in silver foil with blue stars and boxed in a blue box with white stars with a large pale blue Baci in stylised font), the following marks have been registered:

|

|

|

I don't pass judgment on the above marks; they are by way of example only and it is up to each manufacturer to work out which elements of their get-up are vital. Trying to set priorities across a global filing portfolio within budget can be difficult.

Still, there are some marks on the Register that don't appear to protect anything beyond what a plain word-mark registration would have achieved (plain shaped bottles with word marks on them for example) or are so busy (pictures of the whole of packaging covered with logos, pictures and word marks) that you are unable to imagine what third-party use they are designed to prevent.

There may be a range of rights you can rely upon where trade dress or get-up elements are used by a competitor. But if you want to try and rely on trade mark registration rights to protect these then the present state of the law suggests you need to disengage any such elements from the primary word mark (and also any primary logo mark), have realistic expectations about what you might claim to own (as against what is simply common or decorative) and be strategic in how you file any trade mark applications.

Margaret Shearer |

|

Margaret Shearer is a partner and trade mark attorney. She has experience in advising on branding issues and all areas of trade mark and related law and practice, including local and international pre-use clearance, filing and prosecution, opposition and removal proceedings, customs and parallel importation and infringement actions. Her clients include companies involved in computer technologies, internet and IT, financial services, food manufacture, telecommunications, retail and public utilities. |